A precious message for all Australians has been created by First Nations people with publication of Words to Sing the World Alive.

In a gentle, generous and learned collaboration between The Poet’s Voice, an organisation focused on the writing, listening and sharing of poetry in public domains, and editor Jasmin McGaughey, 40 contributors collectively and individually bring together a work offering a deepened understanding of Indigenous Australia.

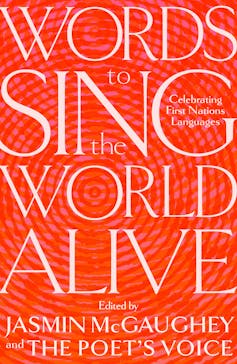

Review: Words to Sing the World Alive: A Celebration of First Nations Languages, edited by Jasmin McGaughey and The Poet’s Voice, (University of Queensland Press)

Full of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages and substantive English translations, this book is about Indigenous cultural life, family and humanity.

Kindled by “spoken-word” events at the National Museum of Australia and Melbourne’s The Wheeler Centre, the thinking and writing in this book encompasses poets, essayists, performance artists, broadcasters, lawyers, authors and academics. While a small selection of these works have been published previously, most are new.

Anita Heiss’ eloquent piece explores the value of learning the Wiradyuri (also spelt Wiradjuri) language inside a “classroom” and in daily interactions as part of her community. Paying tribute to mentors and teachers such as Dr Stan Grant Senior, respectfully referred to by many as “Uncle Stan”, Heiss observes that most students in the class had “been denied the right to speak our language, to pass on our culture […] Learning language is part of rebuilding our nation.”

Elsewhere, Jazz Money introduces readers to “Giyira”, a Wiradjuri word, by showing how it evokes the continuity and connectedness of both the “womb” and the “future”.

Yuin writer Bruce Pascoe, whose heritage also links him to Bunurong people in Tasmania, complements this emphasis, noting that in his Yuin language, “we all rise from the mother’s heartbeat”. Like other contributors, Pascoe laments the fracturing impact and damage of colonisation on Indigenous families, languages, cultures and Country.

Aunty Rose Elu’s essay is nicely positioned at the collection’s outset. She names “Kurusipagiz”, a word in her Kalaw Lagaw Ya language from the Torres Strait, as important for the way it encourages speakers to listen. “What you understand depends on how you perceive my words, which depends on how you listen.”

Listening and learning from respected others is also fostered by Thomas Mayo who uses the word “Amai”, from Kalaw Lagaw Ya to show the value of teaching and handing on knowledge about catching and cooking food, and of sharing a meal with loved ones.

Honouring ancestors

Like Heiss, author Jared Thomas describes the efforts being made to relearn, reclaim, and revive many language forms: in his case the Nukunu language, in regional South Australia.

While it is wonderful to see languages such as Nukunu being learned by young people through community, language courses, universities, and re-naming places, animals and plants, such a process, he reminds readers, is also a way to “honour” ancestors.

The honouring of ancestors is central to a beautiful oral history story told by the distinctive Lama Lama and Bundjalung musician, Kev Carmody.

Titled “Yarraman”, meaning “horse” in his and related languages, this is a tale about his grandfather, a member of the Australian Light Horse Regiment in World War I, and a volunteer in World War II. The value of storytelling and passing on family stories through each generation is central to Carmody’s narrative. He also identifies the value of “Yarraman” to Indigenous people: not only in war, but as a means of transport and in the cattle industry.

In a story titled “Decolonising The Shelf”, Wiradjuri writer Tara June Winch cogently describes her response, at a writer’s event, to a question from the audience about why there had been a recent “explosion” of First Nations writers.

Winch replied to the female questioner that Indigenous people constitute “a culture that has survived by storytelling […] It wasn’t us who had changed, I said, it was her.”

With seasons, the environment, and sustainability a theme of this book, Noongar woman Claire G Coleman describes the “Bilya” a “river, or stream”. Running through the heart of Perth in Whadjuk Noongar Country, Bilya culturally, socially, emotionally nurtures her.

Yorta Yorta woman, Taneshia Atkinson echoes the intrinsic value of “wala”, or water in her language, from a cultural landscape thousands of kilometres away in south-eastern Australia.

Terri Janke, in a story titled “Ged”, a word meaning “home” in her Meriam Mir (also spelt Mer) language, brings readers full circle. Like Winch and Coleman, but from a cultural and geographic vantage point in Australia’s far north-east, including the Torres Strait Islands, Janke creatively weaves the intersections of family relationships, spirits, lands, waters, reciprocity and customary law through the seemingly “simple” but “holistic” and everyday use of “Ged” as home, people, Land.

Jacob Morris’ poetic prose, titled “Gugarra”, Kookaburra, brings to life a highly relevant bird to Gammeya–Darrawal people in coastal New South Wales, and Morris’ personal totem. Here, too, readers are encouraged to understand the enduring interconnectedness of Indigenous lives, words and cultures.

Noongar writer Kim Scott’s story, titled “A Paradox of Empowerment”, paves the experiential way for mind and heart renewal – and a path to truth-telling. His writings, he notes, are always “about seeing things differently”.

Reviewing Words to Sing the World Alive brought to mind a very different but equally compelling book – Dhoombak Goobgoowana: A History of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne, (Volume 1: Truth), also published this year by a university publisher.

Each book is noteworthy not so much for content and style (although both certainly fill gaps in knowledge about culture, language, land and the colonial encounter), but for the extent to which they convey stories about Indigenous Australia’s past, present and what may lie ahead.

If both books had been widely read, understood and talked about prior to the 2023 referendum inspired by the Uluru Statement from the Heart the outcome could have been different for all Australians.

Sandy Toussaint does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.