Beyond the Border brings you human stories about the U.S. immigration system through original reporting from journalist Kate Morrissey and curated highlights from reporters across the country. The newsletter is sponsored by Capital & Main.

In 1990, a woman known in court records as A-C-M was kidnapped by a guerrilla group in El Salvador.

The group forced her to watch as her husband, a soldier in the Salvadoran Army, dug his own grave before the guerrillas killed him, according to the court records. They forced the woman to undergo weapons training and to cook, clean and wash their clothes.

The woman fled to the United States the following year.

In 2018, the U.S. Board of Immigration Appeals found that because of the work she did — even though it was coerced — she had provided support to a terrorist organization and could not receive asylum in the United States.

Now, as the Trump administration moves to designate various cartels and gangs in the Western Hemisphere as terrorist organizations, many asylum seekers with pending cases could meet a similar fate.

San Diego-based attorney Elizabeth Lopez of Southern California Immigration Project said that as soon as she saw President Donald Trump’s Day One executive order that called for the secretary of state to recommend specific cartels and gangs to designate as terrorist organizations, she knew it would affect many asylum seekers.

That’s because in U.S. immigration law, anyone who knowingly provides “material support” to groups determined to be terrorist organizations cannot receive asylum.

San Diego immigration attorney Cheri Attix said the broad definition used in U.S. law goes back to changes made in the wake of 9/11.

“It could be that you paid a bribe at a checkpoint. It could be that you shared food with them. It could be that you provided medical care. It could be that you let them use your parking spot. Anything,” Attix said.

The result, she said, is that the evidence that would show that a group is targeting someone in a way that might qualify them for asylum can also be the evidence that shows they’re not eligible.

Lopez, who focuses on representing asylum seekers from African countries held in Southern California detention centers, said a judge denied asylum to a client she had from Cameroon who was robbed in the woods by a group of young people associated with rebels fighting against the government on behalf of English speakers.

The rebels accused her client of being the enemy and then demanded money, Lopez said. He didn’t have anything with him except some fruit and vegetables and ended up handing those over. The immigration judge found that he had materially supported a terrorist organization, she said.

“They didn’t seem to care about the difference in voluntarily giving them something,” Lopez said. “They point a gun at you and tell you to hand over the cash. You’re not voluntarily giving it to them.”

Lopez said asylum seekers from Nepal who’d been forced at gunpoint to wash clothes for Maoist groups have had their claims denied as well.

There are some exemptions to the material support rule, but the process for getting them to apply in a case can be quite complex, according to Attix.

She said she had clients from Iraq who paid ransom to ISIS when the terrorist group kidnapped their loved ones. Those payments to save their loved ones’ lives meant they were then barred from asylum under the material support law.

“I think if you’re in that situation, you can’t be expected to just say, ‘Oh, so sorry, I can’t give you money. You’re a terrorist,’” Attix said.

Many people who are fleeing threats from cartels or gangs in the Western Hemisphere have paid some amount of extortion money to those groups before the situation reached a point that pushed them to make the choice to leave. It’s common for Central American gangs such as MS-13 or the 18th Street Gang to charge what they call “la renta” to small business owners in areas that they control.

“I am very concerned that people who have been forced to give money to the cartels and gangs, through having to pay a ransom, having their businesses ‘taxed’ by a gang, or paying a smuggler who is part of a cartel, will be found to be ineligible for asylum,” said San Diego immigration attorney Ginger Jacobs.

Asylum seekers from other parts of the world also encounter these groups as they migrate to the U.S. border, particularly as they pass through Mexico, the attorneys said. But those asylum seekers often don’t know the identity of the group robbing or extorting them, which may protect them from losing the chance at asylum. The law says that a person who gives support to such groups has to be aware that they did in order to be denied asylum.

Still, the impact of the designations could help the Trump administration achieve its goals of restricting access to asylum and deporting those who request it.

“They’ve nibbled around the margins so much for asylum that you lose sight of the whole point that we have people who are in danger seeking safety,” Attix said.

A history of racism, deportation and incarceration

As Trump moved forward on his promises to increase immigration arrests, detention and deportation, I looked at the history of large-scale deportations and incarceration in the United States in a two-part series for Capital & Main. Many academics see history poised to repeat itself, leading to generational trauma and economic upheaval. But the descendants of people affected by mass deportations to Mexico in the last century and the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II say they are not going to let the government do that again without a fight.

The Border Chronicle similarly dug into the recent history of immigration detention and the contracts that the Biden administration awarded for border and immigration enforcement that will help Trump with his plans.

Other stories to watch

Afghan asylum seekers who fled the Taliban following the withdrawal of U.S. troops are stranded in Mexico after the Trump administration canceled the CBP One app that scheduled appointments for migrants to request protection at U.S. ports of entry under former President Joe Biden, Borderless Magazine reported.

The Trump administration began holding some migrants at Guantanamo Bay, including several men whose families told news agency EFE that their loved ones were not members of any gang as the administration alleged. The families said the men had fled Venezuela to request asylum.

According to The Texas Observer, Trump’s choice to lead the Drug Enforcement Administration previously worked at a surveillance tech company that has contracts with ICE, the DEA and other government agencies. Derek Maltz oversaw government relations for the company but was not registered as a lobbyist.

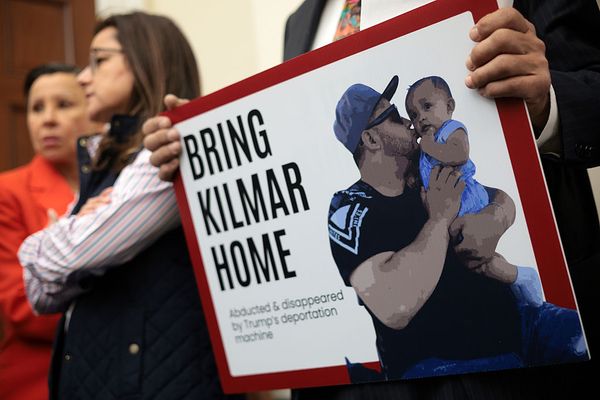

People across the U.S. have protested the Trump administration’s treatment of immigrants, particularly the increase in ICE arrests in the past week and a half. On Feb. 3, many observed “A Day Without Immigrants,” including a restaurant in San Diego that closed its doors in solidarity and was vandalized.

ICE is updating old press releases, causing them to show up in the first page of Google searches to create the appearance of more recent enforcement activity, The Guardian reported. According to NBC, ICE has released several hundred people on electronic monitoring after arresting them in the weeks since Trump took office.

After a ride-along with Border Patrol, the Associated Press reported on the contrast between Trump’s rhetoric of a chaotic border and the quiet and calm that reporters witnessed. The AP also reported that a San Diego migrant shelter run by Jewish Family Service hasn’t received any migrants since Trump ended CBP One appointments. The shelter has served more than 248,000 people since it opened in late 2018.

For Capital & Main, I followed up on ICE’s decision in the last year of the Biden administration to transfer people in its custody out of San Diego even though they had attorneys here. Because many had attorneys through a county government program, the moves meant that they no longer had legal representation.

A podcast from The Border Chronicle looks at Texas’ Operation Lone Star and what it could mean if the program that has deployed thousands of National Guard and state police to the border becomes a national model under Trump.

In a subscriber-only piece, the Arizona Daily Star revealed how the Department of Justice’s prioritization of immigration offenses under Trump will take away resources from cases involving violent crimes as well as drug trafficking, child exploitation and white-collar crime.

The Houston Chronicle looked into why the website went down for the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, which so many of us who work on immigration information depend on for reliable government data on everything from immigration courts to ICE arrests. TRAC has since relaunched at a new domain.