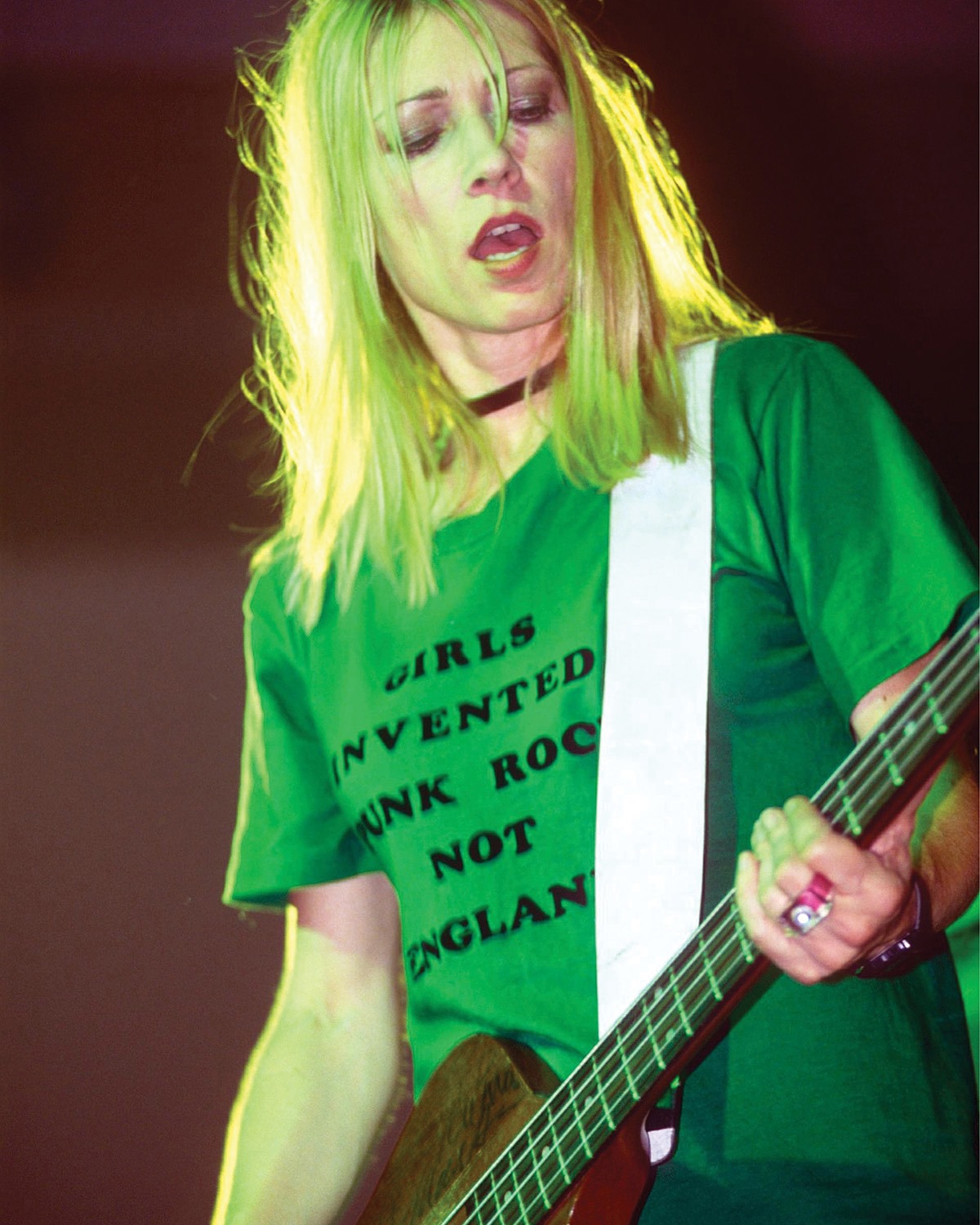

Kim Gordon – the American musician, singer and songwriter turned visual artist – disavows being an icon. She even published a book called No Icon in 2020 to drive home the point. But she is an inspirational figure for many, us included, and has a place in our recent Wallpaper* USA 300, a celebration of creative America.

We look to our cultural heroes and make field notes for living, thinking that if we listen, watch, read what they do closely enough, we can absorb through some osmotic process a bit of what has us in their thrall.

We have been listening to Gordon’s music with bands Sonic Youth and Body/Head, and her solo projects; reading her autobiography Girl in a Band, and collections of criticism; wearing clothes from her fashion label X-Girl; and looking at her visual art, which she has been steadfastly pursued since Sonic Youth disbanded in 2011.

Here, Wallpaper’s Mary Cleary speaks to Gordon about her recent show at 303 Gallery in New York, her relationship with technology, her advice to young artists, and other valuable insights that bring us a little bit closer to the icon.

Kim Gordon in conversation

Wallpaper*: In your recent show at 303 Gallery, you examined our increasingly entangled relationship to technology through a number of abstract canvases, many of which had iPhone-shaped holes cut into them. Looking at the pieces made me wonder about your own relationship to technology.

Kim Gordon: I am addicted to my phone. I realise that it kind of rules our life, but I feel like people seem to equate technology with human evolution and it doesn't really seem to line up that way. Humanity has evolved to a certain point but if you look at what’s going on in the world, and here in America, it’s not evolving. It’s going backwards.

W*: Did making the pieces give you new insight into how our technology is impacting our culture?

KG: I mean, not really [laughs], no. It was kind of funny how they're abstract and basically anti-painting but some people look at them and say, ‘Oh, it looks like skyscrapers.’ People always want to see something and that's kind of interesting – that they're looking at a shape that's basically empty but yet they see a city.

I guess that the thing is that everything looks better on an iPhone, including some of my art I think [laughs]. But, you don't have a sense of the scale of anything. You don’t have a sense of context, really. So it's kind of covering up just by what it's not showing. It’s more a person’s choice that tells you something rather than what they’re shooting.

W*: Looking at the show made me think about an essay you wrote for ArtForum back in 1983 called ‘I’m really scared when I kill in my dreams’. In it, you wrote about the power dynamics at play between a performer, their media image and the audience during a live performance. How the performer makes themselves vulnerable to the public and the risk inherent in that is what makes the experience of seeing a gig so ecstatic. But now, four decades later, when everyone is in a sense constantly performing, how does that dynamic change? Do performers still have the same resonance they once did?

KG: Well, people have become more sophisticated about branding themselves, and using elements of vulnerability [to further their brand]. Like Taylor Swift, I actually hardly know anything about her, but the sense I get is that her initial appeal was of someone who was approachable. So by writing lyrics about her ex-boyfriends, or break-ups, or whatever, [she] is her using vulnerability [in an intentional way].

But the power of being in a group together all for the same reason – to let yourself open up to this person on stage, be swept up in the feeling of joyousness or entertainment or whatever, that hasn’t changed.

W*: Speaking of that group mentality, you have performed various and varied group and solo projects. What does creating work on your own afford you that working collaboratively does not?

KG: It's different. When you’re collaborating, it gives you a confidence to make something neither of you would have ended up making; but when you’re making it on your own it's kind of… head-scratching [laughs].

I like being in Body/Head with Bill [Nace] and I have this solo band that I tour with, but I don’t necessarily want to be in a band with more than one person anymore.

In terms of creating stuff and recording, Bill and I are on the same wavelength and I just really don’t want to get into band dynamics anymore. I’ve done that. [Collaborating with one person] keeps it really focused on just the music and being able to feel really free in the most pure form of music-making.

W*: One thing that struck me when I read your book Girl in a Band was how uninhibited you have always been in your creativity: you join a band even though you have little musical training; you want clothes you can’t find at the store so you start X-Girl; Gus Van Sant asks you to be in a movie so you start acting. Where does that self-belief and that drive come from – is it innate or is it something that can be cultivated?

KG: Well, I never had a back-up plan for moving to New York and doing anything other than making art. In fact, I specifically didn't learn how to type in high school because I didn't want to be a secretary. But I just kind of fell into music, and X-Girl was just kind of happenstance – me and my friend were asked to start this line but we never really saw ourselves as designers.

I just mostly see myself as a visual artist who does these other things. If I was to sit down and write like a conventional novel… I mean, I really wouldn't. I'm not a writer and it wouldn't work. But in general, I have to approach things sort of sideways and kind of feel my way into them.

W*: Was there ever a moment where you were pursuing something creative and faltered?

KG: Well, I often feel like that when I'm making visual arts. But I also like the idea of, and I have tried to make, paintings that fail. So that instead of always thinking, ‘I want success’, what would it be like if you made something that actually didn’t work?

W*: Did you ever show those works?

KG: No, they didn’t actually do what I wanted. They didn’t fail in the right way. It was too ambiguous what they were supposed to be.

W*: So when you're creating, do you always have a message in mind or is it something that organically emerges during the process?

KG: It helps if there is a definite show and a context, but mostly it's just having an idea. Like I did this series of paintings for a show at the Museum im Bellpark outside Lausanne last summer [2022]. The show was basically about gentrification, with these pieces of pre-made fabric with the names of real estate developments in LA painted on them and displayed in this museum that is basically a mansion.

There's a video I shot when I went for my site visit where I interviewed the two quite lovely guys who run the place, the director and the curator, and I sort of did this hidden voice going through the rooms, like [puts on a deep voice] ‘Master Suite’, ‘Kids Room’ as if I was a double agent, which is what it was called.

But that was because the museum is owned by this town which is a suburb of Lausanne and the discussion always comes up of if they want to keep funding this as a museum. So the show was kind of touching on those things.

W*: Is there any recent project you've been particularly proud of that you find yourself returning to frequently?

KG: I was very proud of that [Lausanne] show actually, because it had many different layers to it, and I love those sort of situations, where it's kind of a domestic setting and not a white box.

It had one of these two videos I made with this documentary director friend of mine; [in] the second one, which wasn’t in that show, it's me in a junkyard with a bunch of cars with my guitar and there’s something dystopian about it. Like, I'm a stranger, an alien that wanders into this place.

W*: Are there any artists whose work is really exciting you now?

KG: I like Seth Price, Jutta Koether, Josephine Pryde, Loretta Fernihold – who actually did a bunch of videos for my last tour to play behind me while I play – John Miller, and one of my absolute favourites is Klara Lidén.

W*: Is there any advice you have for artists who are just getting their start now?

KG: I guess, just don't be in a rush. It’s weird because their world is so commercial right now, but I just feel like it's important to read a lot and have fun with it.

In your early twenties, people expect you to know what you’re doing and that’s just the hardest time. At least it was for me. Even though I knew I wanted to be an artist, I just was not very together. I didn’t know how to go about it. Unless you go to school with a bunch of other artists and you move to New York together, it's just difficult.

W*: I guess it’s that fear of not knowing if it's going to work out.

KG: Yeah, and also just knowing how to, like, get a show in a gallery. The art world especially is such an elitist club, quite frankly.

W*: Do you think that will ever change?

KG: No, it won’t change in that way. But also, should it change? Does every person know about the world of science? You know, there are different levels in the art world. So, there are different things you can get out of it at different levels.

But science, politics – those are worlds – and every world has its own elite aspect and is inaccessible and incomprehensible to most people unless you actually studied it. So people have weird expectations about the art world.

W*: What projects do you have coming up?

KG: There’s a dance project I’ve worked on with [choreographer, artist and educator] Dimitri Chamblas that's premiering in Brussels at the beginning of October [2023], and I’m working on a new record.