Kevin Lambert’s last novel, Querelle of Roberval, ended with infanticide, necrophilia, cannibalism, and the ritualistic, livestreamed suicides of three teen delinquents suffering from HIV/AIDS. Readers familiar with it (and its only slightly less violent predecessor, You Will Love What You Have Killed ) may be anxious to know how, in his latest novel, the ante can possibly be upped.

In May Our Joy Endure, the Québécois writer shifts his attention from the factory-town horrors of the Saguenay (where he was born and raised) to the more subtle monstrosities that lurk in Montreal West mansions. The book opens with a virtuosic party scene that carries on uninterrupted for sixty-two pages, in which Montreal luminaries gather in “a ravishing apartment, high ceilings, wood mouldings, white marble floors.” One of the guests is Céline Wachowski. As the narrative flits between the consciousnesses of the guests, we discover that Céline is many things: a feminist pioneer, a shrewd businesswoman, a television personality with her own Netflix show, and a celebrity architect whose company, Atelier C/W, has created stunning buildings in cities around the world, from San Francisco to Abu Dhabi. Céline is also suffering premonitions of disaster.

The disaster, when it hits, is relatively straightforward. Céline has been commissioned to build the Montreal headquarters of Webuy, an Amazon-like company. When a man evicted during Webuy’s construction winds up unhoused and takes his own life, she becomes the focus of the city’s rage at the ravages of the housing crisis. A series of New Yorker exposés reveals that, despite her spotless public persona, she has the usual dirty laundry of a billionaire. Money stashed in tax shelters, unsafe working conditions in a factory affiliated with one of her companies, and investments in a successful “Airbnb clone” that has contributed to skyrocketing property prices and rents across the Western world.

Céline is shocked by the charges levelled against her; having risen from modest origins, she has always seen herself as a tribune of the oppressed. She continues with the headquarters project even as the protests on the street and in the media grow more intense—protests that she herself, on a fundamental level, agrees with (“she supported the movement,” writes Lambert, “and she was touched by those who were standing strong. It was essential to put cities to the flame and sword every fifteen years.”). Céline is not a cardboard villain. She is a good liberal, with a liberal’s concern for justice, equality, a brighter future for everyone, etc. The criticisms hurt precisely because they come from the people she always thought of as her people.

Eventually, the public pressure becomes too strong. The board of Atelier C/W votes to remove her, and her public humiliation is complete. Céline retreats to her mansion on the Rivière-des-Prairies to read Proust and ruminate on the fickleness of the world. As she descends into bitterness, recrimination, and terrible, crushing guilt, the novel takes another turn. When her few remaining friends gather for her seventieth birthday party toward the end of the novel, there is a sudden eruption of violence: protesters invade her home and set about destroying the beautiful objects she has carefully collected over a lifetime.

In Lambert’s earlier fiction, such violence would have been apocalyptic and revelatory, a cleansing flood to close the novel. But in May Our Joy Endure, the literal violence of the protesters is only a prelude to the much more devious and calculating violence Céline unleashes on those who have wronged her, and it reveals Lambert to be one of our most subtle and perceptive novelists.

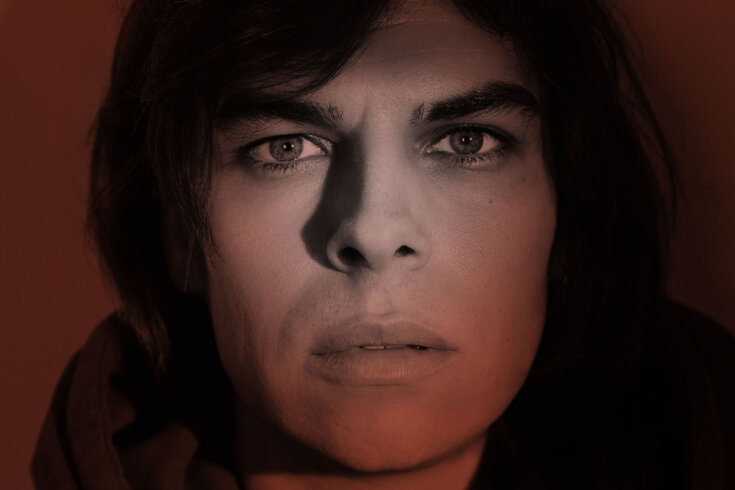

Lambert, born in 1992, is not yet a household name in English Canada. But in his home province, he is a decorated, generational talent. A number of his laurels come from France: the Prix Médicis, the Prix Décembre, and the Prix Sade. He was a finalist for the revered Prix Goncourt, whose previous recipients include Marcel Proust, Simone de Beauvoir, and Marguerite Duras. Lambert also isn’t above throwing out a sharp elbow at Quebec’s elite: he recently gained notoriety for a public spat with François Legault. After the premier praised May Our Joy Endure on social media for its “nuanced critique of the Quebec bourgeoisie and lobby groups and journalists looking for scapegoats for the housing crisis in Montreal,” Lambert upbraided him for exacerbating the very problems the novel was criticizing.

No one familiar with Lambert’s first two books could have made Legault’s mistake. You Will Love What You Have Killed was a brutal tirade against the hypocritical degeneracy of small-town Quebec, and Querelle of Roberval, which centred on labour disputes in a mill town, aimed its fire squarely at the neoliberal extractive economy. Working within a recognizable tradition in Québécois and French literature, one that includes writers like Marie-Claire Blais, Nelly Arcan, and Jean Genet (Querelle of Roberval recalls Genet’s Querelle of Brest), these books were paeans to misanthropy and radical, uncompromising queerness. They were also gorgeous, lyrical, and tender—a ballet performed in an abattoir.

Among the highlights of reading Lambert in Donald Winkler’s superb English translation is his elegant and vicious style, which relies on long sentences that achieve velocity by piling clause on clause, adjective on adjective. He often describes things multiple times, deepening and widening our sense of what is at stake for his characters through verbal monomania. Céline is “abject,” but she is also “the perfect product of an abject society, the exact abject consequence of Quebec’s abject stupidity and ignominy perfectly embodying the abuse, the opportunism, the destruction, the corruption, the tyranny, for which she has been condemned.”

It is prose perfectly suited to the subject matter of May Our Joy Endure, a novel fixated on the gaps between how people (especially the rich) perceive themselves and how they are perceived by others. Lambert captures something key about a certain kind of affluence—that of people who don’t just want to be rich but want to be loved. The very reason Céline is well known enough that public opinion matters to her is that she stands for a certain set of values.

She isn’t just an architect; she practises “ethical architecture.” She wants to make beautiful, important buildings that improve the lives of those who live in them. Yes, of course, her actions prove she also wants money, but when she is unceremoniously removed from Atelier C/W, it doesn’t make her any less rich (in fact, in one of the pitch-perfect ironies that makes the novel such a joy to read, Céline sees her own defenestration coming, shorts the company stock, and turns a profit off her own cancellation).

But this isn’t enough on its own. She has the heart and soul of an artist and is therefore playing a game far more complicated than simple finance. To survive, she must perform empathy, kindness, and humility. She must represent the ideal of feminist empowerment without ever revealing the ruthlessness needed to achieve such a position. Her audience wants her to be, simultaneously, an avatar of stratospheric success and an ordinary person like themselves.

The problem is that she is living through an age of anger as powerful as it is unfocused. Tellingly, it is Céline, the architect, who attracts that rage, rather than Webuy alone. This is because Céline is a recognizable human being, a comforting presence on television, a woman (and, of course, it does matter that she’s a woman) who has presented at the Golden Globes and championed good causes. It is precisely wanting to be seen as good that makes her so vulnerable. It opens her up to charges of hypocrisy that other, far more compromised actors don’t face, for the simple reason that they aren’t feminist celebrities.

The anger latches on to her not because she is in any way extraordinary in her wrongdoing but because she has let the mask slip. And the anger is so palpable, so justified by decades of soaring inequality, the destruction of industries, and abuse by the powerful that it has to go somewhere. It is exactly this kind of omnidirectional anger Lambert wrote about in his previous novels, only seen from the other side. And this is one of the things that makes May Our Joy Endure such a complicated and slippery book. Affluent characters in contemporary anglophone fiction are often depicted as either idiotic or depraved, which is understandable given the rapidly widening gulf between the economic elite and everyone else.

But it makes Lambert’s attempt to capture what it might be like inside a billionaire’s head a high-wire act. We spend so much time immersed in Céline’s consciousness that it can seem as if Lambert is secretly on the side of the Célines, who are, after all, lovers of literature, art, fine things, and liberal values. It would not be hard for some readers to call this book an attack on “cancel culture” or a defence of the high-flying rich—as the premier of Quebec seems to have done. It would have been safer to remain in the moral universe of You Will Love What You Have Killed and Querelle of Roberval, where the rich are straightforward villains. But Lambert is not a safe writer.

I suspect he is interested in Céline’s subjective experience because he is the kind of novelist who is interested in everyone’s subjective experience. And what experience has been more compelling over the past decade than that of the cancelled? To wake up one morning and discover that millions of strangers hate you, to have your darkest sins broadcast before the world, to watch your erstwhile friends line up to denounce you, to see the story of your life rewritten before your eyes. What would it be like to suddenly see reality so clearly? Lambert’s descriptions of Céline’s guilt and bitterness are exquisite, but he also writes perceptively about the internal justifications of her po-faced colleagues, who can now admit that they always had a bit of a problem with Céline, and who think the protesters have a point and it’s high time they stepped out of Céline’s shadow to pursue their own projects.

The problem bedevilling Céline’s world, and perhaps ours, is a collapse of the political framework. As the mass movements of the past have been bankrupted and hollowed out, activism has tended to coalesce around particular causes rather than concrete visions for the future. Party politics, meanwhile, has become a matter of temporary alliances and strategic rebrands. Lambert understands that the old ideologies governing Quebec in the twentieth century—trade unionism, sovereignty, socialism, nationalism, Catholicism—have largely run out of juice.

What remains are individuals and economies (the financial economy, the attention economy). The vacuum left by mass politics is filled by moral campaigning on the left and conspiratorial fascism on the right. Neither has any real solution. Both look for someone to blame. It’s Lambert’s ability to depict this situation without offering false comfort that elevates his work.

The true horror in May Our Joy Endure lies in the near impossibility of assigning blame: when no one is truly in control, no one can be held accountable. The person serving the eviction notice is following the orders of housing management; housing management takes its cue from the corporation; and the corporation’s CEO considers the interests of the shareholders, who may not fully know what they’ve invested in. Everyone is guilty.

In one of many such exchanges, Céline, confronted about her tax avoidance strategies, says she needs to be smart with her money, because if she isn’t, her competitors will eat her alive. Instead of an architecture firm led by a socially conscious woman, the Webuy headquarters will be built by some conservative white guy. Get rid of Webuy and you’ll just have some other corporate mass-market nightmare to contend with. It’s a common bit of sophistry, but not without some truth. There is no spider sitting at the middle of a web. The web itself is the problem, and we’re all caught in it—hence our impotence, our rage, our guilt, our shame. At a time when many fiction writers feel pressure to write socially useful literature, Lambert’s refusal to deal in solutions feels like an invigorating slap in the face.

Perhaps the clearest articulation of this ethos comes toward the end of the novel, when we get a meditation—through Céline’s eyes—on evil:

You think you are responding to an aggression, but you are the aggressor; you think you are forestalling a fire, but you are doing the burning; you think you are preventing a drowning, but you are holding under water the blue, suffocating face that is drawing us to the bottom.

These thoughts should be understood as part of Céline’s development as a character, not as a thesis statement for the novel. But given that in Lambert’s first novel someone named “Kevin Lambert” drives over a little girl with a snowplow, it’s hard to escape the sense that there is an element of sincerity here. This is a novelist who always understood that the most dangerous people are the ones who refuse to acknowledge their own capacity for harm—who cling to the idea of their own goodness as if it could possibly save them.