As Christmas approaches, children in many parts of the world look forward to a visit from the potbellied Santa Claus, who comes down chimneys carrying a sackful of gifts over his shoulder. In Japan, some children also wait for Hotei, a jolly Japanese god with a rotund frame who carries a similar bag full of treasures. Hotei’s visit, however, coincides with the new year.

As a scholar of East Asian religions who studies deities’ transformations over time, I’ll often explain to my students that cross-cultural encounters produce new understandings and images of gods.

Since the late 19th century, Japanese and Western observers have remarked on the similarities between Hotei and Santa Claus, and some writers even identify Hotei as the Japanese Santa Claus. This identification has grown even stronger in post-World War II Japan, where Christmas became a widely celebrated holiday following the American occupation that lasted until 1952.

From Zen monk to Laughing Buddha

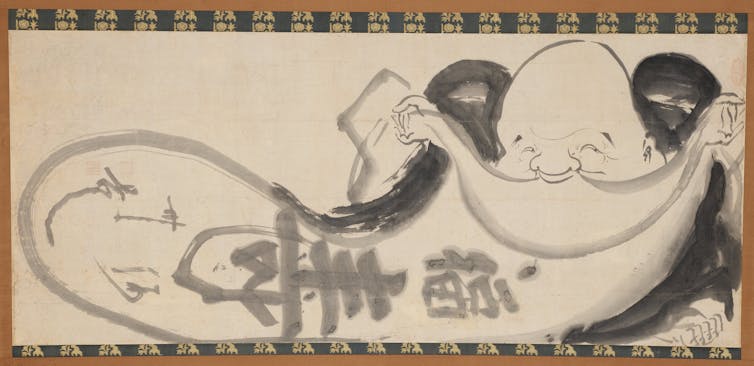

The name Hotei is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese “budai,” which means “cloth bag.” In Japan, Hotei is also known as Hotei oshō, or “monk Hotei,” which refers to his origin as a 10th-century Chinese monk.

Hotei belongs to the Zen school of Buddhism, which celebrates simplicity and rejects the desire for fame and fortune. Zen texts portray Hotei as a wandering monk who is content to live a humble, simple life. He carries a large sack full of odds and ends and shares his “treasures” with children.

Some texts even identify Hotei as a buddha. Buddhism teaches that there were multiple buddhas in the past, and there will be more buddhas to come in the future. The most recent buddha – the buddha most Westerners think of when they hear the word – was called Siddhārtha Gautama or Shakyamuni, and lived about 2,500 years ago. The next buddha will be Maitreya, or Miroku in Japanese.

According to one 13th-century Chinese text, a friend noticed that Hotei had an eye on his back and recognized this as a sign of buddhahood. This same text suggests that Hotei is an incarnation of the future buddha Maitreya.

One of the Seven Lucky Gods

Hotei’s well-fed appearance and bag of treasures represented abundance in China and Japan. As a symbol of good fortune, Hotei was included in the set of Seven Lucky Gods, which developed in Japan by the 17th century. Along with Hotei, this set brought together other Buddhist gods – Daikokuten, Bishamonten and Benzaiten – with Chinese gods of longevity and prosperity and the Shinto god Ebisu. Each god is associated with a magical object and a specific virtue. Hotei’s object is his bag that magically remains full, and his virtue is generosity.

The Seven Lucky Gods do play a role in a Japanese holiday – but on New Year’s, not Christmas. In the first few days of the new year, the Seven Lucky Gods steer their treasure ship from the heavens to earth. On the first night of the new year, children place under their pillows a picture of the seven gods on their ship. This is supposed to bring a good dream, a sign of good luck for the year ahead.

As one of these lucky gods, Hotei is known for being fond of food and drink, and even serves as the patron deity of bars and restaurants.

The Japanese Santa Claus?

Given the many similarities between Hotei and Santa Claus, including the roles they play in the holiday season, it is not surprising that people both inside and outside Japan have conflated Hotei with Santa Claus.

American Christmas differs from its European predecessors by combining elements from multiple countries, especially Germany and England, to create a new kind of celebration. American representations of Santa Claus — including the popular image that first appeared in a Coca-Cola advertisement — also transformed the European St. Nicholas, Father Christmas, Père Noël and Sinterklaas into a distinctively American figure with his red and white suit, sleigh and reindeer.

Japanese Christmas developed its own unique customs, such as eating at KFC and buying strawberry-adorned Christmas cakes. While many Americans celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, in Japan, with its tiny Christian population, Christmas is wholly secular.

Accounts of Christmas in Japan often emphasize Hotei’s role as Japanese Santa Claus, and describe Hotei with eyes on the back of his head so that he, like Santa, can constantly observe children to determine whether they truly deserve presents.

This shows how cross-cultural encounters have changed ideas about Hotei: The eye on Hotei’s back has been reimagined as eyes on the back of his head so he can determine, like Santa Claus, if kids have been “naughty or nice.”

However, not everyone in Japan is convinced that Hotei is the Japanese Santa Claus. In Japan it is still Santa Claus, not Hotei, who gives children presents on Dec. 25. Still, every year in December, revelers put a Santa hat and beard on the Hotei statue in Tokyo’s Maitreya Temple, or Mirokuden, which shows how common the identification of Hotei with Santa Claus has become.

Megan Bryson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.