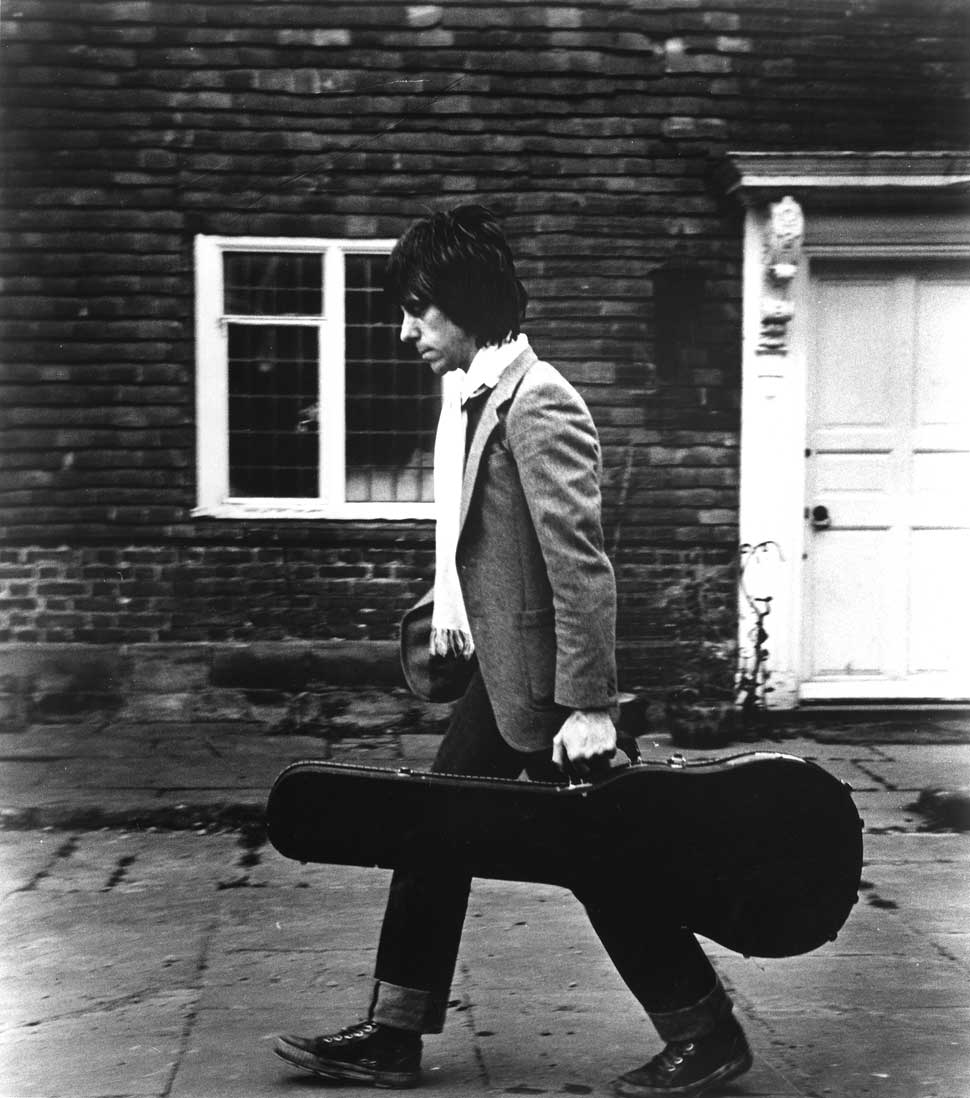

"The day I get dictated to, I would pack it all in," the late Jeff Beck told Classic Rock in 2006, looking back on a career that had taken him from The Yardbirds to the brink of superstardom, before his preference for unexplored territory took him on a path like no other musician. This interview has never appeared online before.

In 1990 the Observer newspaper polled a number of the world’s top guitarists and asked them who they thought was the best in their profession. The guitar player who came top of the list did so by quite some margin. It was the same guy who Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour described as “the most consistently brilliant guitarist over the past 25 years”; who Boston’s Tom Scholz has called “the greatest lead guitar player of all time”; the guitarist that guitarists look up to: Jeff Beck.

At the star-studded Leyendas De La Guitarra Festival in Seville, Spain, in October 1991 – two days of mesmerising performances (or guitar porn, depending on your point of view) from the likes of Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, Brian May, Joe Wash, Paco de Lucia and Phil Manzanera – sitting in the hotel bar on the last evening Satriani gazed into the distance, smiled and mused: “But Jeff Beck – where were you? Jeff should have been here, and he should have played Where Were You, and it would have just floored everybody.”

And he was right. But as delighted (and surprised) as Beck is to be acclaimed and appreciated – and, most importantly, by his peers – it’s not the kind of self-congratulatory notion that is likely to ever enter his head. More self-effacing – seriously self-doubting, even – than one is used to coming across in a music industry increasingly driven more by fame-seeking ego than by talent, you won’t find Beck blowing his trumpet about his guitar playing.

Having started his musical education playing piano, then moved to playing drums along to jazz records, then spent time with a cello between his legs, a short-trousered Jeff Beck eventually found where his musical heart lay one day in 1956 when he went to see the movie The Girl Can’t Help It, and sat in the dark cinema entranced by Little Richard, Gene Vincent and, especially, Vincent’s guitar player Cliff Gallup. The seeds were sown and immediately took root. Beck the guitarist began to grow.

One of the original holy trinity of British guitarists – along with Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page – who came through in the 60s (each of whom, amazingly, was at various times in The Yardbirds), at the expense of commercial success Beck has continued to explore new ground while the other two found their niche, dug it ever deeper and continued to mine commercial gold.

More naturally gifted than Clapton, more inspiration-driven than Page, more imaginative than both of them, Beck is a true maverick. Pig-headed, famously moody, doggedly determined, he does what he wants, how he wants, when he wants – if he wants. Clapton sold out, Page burned out; Beck continues to push new buttons and push the envelope, even if he does occasionally go into PowerSave mode, take extended sabbaticals (to build hot-rods, look after stray dogs and enjoy his beautiful gardens and 74-acre spread in Sussex) on a whim and disappear off the radar – sometimes for years at a stretch.

In the post-Yardbirds 60s The Jeff Beck Group’s Truth album provided the touchstone and the blueprint for Jimmy Page to use to fashion Led Zeppelin. In the solo 70s Beck hit a purple patch with the breathtaking Blow By Blow and Wired, a pair of remarkable benchmark jazz-rock fusion albums recorded with Beatles producer George Martin.

In the 80s the guitarist hit his rock peak with There And Back and Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop, both of which brought together dazzling technique, smouldering aggression and heart-melting melodies in virtuoso displays of controlled power and gossamer touch.

In the 90s Beck dug into dance grooves with real aplomb and artistic success, on the album Jeff outdoing the likes of The Prodigy at their own game and repeatedly dealing himself a winning hand with thumping, anvil-heavy beats and fierce, flashing electro rhythms.

But all those are just some of the highlights in a glittering 40-year recording career in which the four-time Grammy-winner has drifted, sometimes by design, between the public spotlight and the shadows, but all the while maintaining a constant presence in the eyes of those who know.

He was on the shortlist (along with Rory Gallagher, Mick Ronson, Harvey Mandel and Ron Wood) to join The Rolling Stones when Mick Taylor quit the band in December 1974, but tore up his jackpot-winning Lottery ticket. (“I mean, the money was tempting. But I would have been half-dead, and my reputation would have been shot.” According to legend, following the auditions in Rotterdam Beck’s parting shot to Mick and Keith was: “Call me when you’ve got a rhythm section.”)

Beck is the man that Roger Waters, Jon Bon Jovi, Duff McKagan, Paul Rodgers, Stanley Clarke, Mick Jagger, Tina Turner, Brian May and Sir George Martin, among others, pick up the phone and call when they need a guitar player to sprinkle some fretted fairydust on their albums. Jeff Beck is, after all, officially the greatest living guitar player.

Stylistically, you’ve moved around a lot over the years, taking in rock, blues, jazz, electronica and whatever else. That’s probably been great for you, but has it confused your audience?

Yeah. I hope it did, ha ha. I dunno. I just can’t see having a jigsaw-puzzle career in which everything slots in and has a meaning. My tastes change, my diet changes, I do things to my cars that I never dreamed I’d do – one minute this colour, the next another colour; no fenders, then they have got fenders. Life changes, doesn’t it?

It looked for a time, with some of the stuff on albums like Jeff, that you had decided to head off along the techno route and into the world of dance grooves.

If we’d had a hit with the dance thing… I wanted to embrace the dance groove with listenable music, in terms of Rollin’ And Tumblin’. And if that had made any impression, then I would have gone on that route and we’d have had a different audience. But it didn’t get an outlet. A club in Florida or Germany or London playing it once isn’t going to get it.

You’ve got to be like Paul Oakenfold and people like that. The dance crowd wouldn’t get to hear it because of my name; they’d just think The Yardbirds or whatever. How the hell would we ever get the publicity to override that, to put that record straight? You’ve got to do something sensational, like chop down a speed camera or something [laughs]. We did think of putting it out under a different name, but…

Do you genuinely think that not many people are interested in what you’re doing or in coming to see you play?

I haven’t nurtured a career here [the UK], I think that’s what it is. It’s all my fault. I mean, I turned my back on the austerity of England. And who wouldn’t, you know, when you come from the sort of place that I did, and you see LA for the first time and a whole new world of opportunity? Also, there were no real offers of substantial money to keep the band going. If you could see the accounts from the Rod Stewart band [the Stewart-era Jeff Beck Group in the 60s], there’s a very good comedy script there. It was just pathetic

There have often been long gaps between your UK tours, notably one from 1980 to 1990’s Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop tour, although you did release the Flash album in between.

The 80s weren’t my time. I liked Prince and ZZ Top’s Eliminator and that was about it. I wasn’t going to try to sell anything about me, whether it was old, new, or surreal, tomorrowland music, because it was hopeless. The whole musical playground was a joke. The record label execs were more important than the acts; even the bloody retailers were snorting coke and telling you how to play guitar. Bollocks to that.

Effectively sitting out the 80s – even if it was by default – may have turned out to be a good career move, even if it didn’t seem like it at the time.

Yeah, I kept out of the way. And I think there will be a time soon when I’ll have to pull hard, you know. And that will mean a proper album – a seriously good album to let them know I’m about

In 1990, in a poll of celebrity guitarists by the Observer newspaper, you were voted the greatest living guitarist – by some margin. David Gilmour of Pink Floyd has called you “the most consistently brilliant guitarist over the past 25 years”. What do you make of that?

Those sort of remarks are what keeps me going, really. Brian May, who is just an incredible technician and a masterful recording artist – the things he’s said about me. I don’t really care who trashes me in the papers, people with less qualifications, it just goes over straight my head now. I’ve got a letter from Charlie Mingus [whose Goodbye Pork Pie Hat Beck covered to stunning effect on Wired], from when he was just about suicidal, I guess, saying he loved the way I played. I’ve still got that letter. If anybody gives me shit I just hold that letter up.

You tour sporadically, you record when you feel like it. Over many, many years you’ve renovated a beautiful old house; you’re a keen and knowledgable gardener; you’re well-known for rebuilding hot-rods. Whereas most musicians seem to fit their downtime life into their career, there seems to be a sense in which you fit your career into the other part of your life.

It’s just the way it is. I suppose [co-managers] Ralph Baker and Ernest Chapman could lay claim to my longevity being due purely to their prowess as management, in the discreet way they’ve kept me out of the limelight [laughs]. It wouldn’t surprise me in the least if they laid claim to that. But I tell you, I’d much rather be working and having fun on stage. But there is some wisdom in not going out and flogging yourself to death, you know. I mean, I want to be me; I don’t want to be anything else. It would be great to have financial security, but what does it mean? Just keep happy and healthy, and keep out of the way and don’t piss people off.

You have often been called – in a complimentary way – a maverick. Are you happy with that?

Suits me. The day when I get dictated to as to what I can and can’t do, I would pack it all in and play just for my own enjoyment.

If you could have recorded only one of your albums, which one would it be?

I don’t know. Why do you bastards think of such awkward questions? To narrow albums down to one is so senseless. They all suck.

Given all the reformations these days, how would you feel about putting The Jeff Beck Group back together, even for just a handful of shows?

Nah. I’m not secure enough to do that. I think that would send out wrong signals. The fact that I would have time to do that would mean that all else musically had failed, in a way. We skirted that a little bit. We got close when I went up to play with Rod on one of his shows. We rehearsed, and I could clearly see that it was going to be a major train wreck. For one thing he wanted to sing People Get Ready, which is in the key of D. I’d worked out this fantastic intro, but he couldn’t sing it in D, it was in C. So that intro went out the window.

Ronnie was on bass – six-string bass! Couldn’t hear the drummer because he was in a glass cabinet – sealed off with cement, y’know – so there was no chance of hearing any cymbals. And I thought, no, I can’t put these deaf-aids in my ears and pull off a proper performance. That was me, Rod, Ronnie and Rod’s drummer, so it wasn’t an acid test of whether that band [The Jeff Beck Group] would survive or be a viable proposition. But it was close enough for me to not want to do it [laughs].

You haven’t kept together any of the line-ups you had for any real length of time. What are you like as a band leader?

Terrible. Fucking world’s worst. I never like to offend anybody, and I never want to undermine their confidence. And I suppose you can say it works for me, even though I’m probably not getting even a fraction of what I could get out of the band if I was a complete bossy bastard. But don’t get me wrong, I won’t put up with things that are wrong. I won’t let that go. And if I firmly believe that what I’m doing is right – like choice of songs, placement, artistic stuff like that – then I’ll do it. I may be off-kilter sometimes, but normally I can feel what an audience expects; I can read an audience. And I’m the one out front and listening to the response. And it’s my name on the tickets and on the records.

What was life like in The Yardbirds?

It was alright. I was like a kid in a candy store for about a year. I mean, I got my red carpet right from the beginning. I got a guitar – I didn’t even own a guitar when I joined The Yardbirds, I borrowed Eric’s, I think. Then I bought an Esquire off John Walker from The Walker Brothers quite early on. Then I made some money and I bought a Les Paul. I haven’t played a Gibson for years. Too heavy. I’ll leave Gibsons to Slash and Jimmy Page.

The Yardbirds’ ex-manager, Simon Napier Bell, said in his hilarious book You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me that The Yardbirds were a right miserable bunch.

Well, when he came along we were, because we didn’t know where we were going. Giorgio Gomelsky [early manager] had failed, and nobody knew where the money went. That didn’t make any difference to me, because they only paid me 20 quid a week anyway.

And I kept getting ill all the time. I was genuinely sick. But because I’d swung the lead before, pretending to be ill, when I really did get ill they didn’t believe it. And I got kicked out. That was a terrible blow. I didn’t really want to carry on, but I didn’t have anything else to do. And then with my last-ditch attempt to put my life back together I got Rod. It [The Jeff Beck Group] was a ground-breaking band.

Does the old chestnut of The Jeff Beck Group’s debut album, Truth, effectively being used by Jimmy Page as the blueprint for Led Zeppelin still rankle?

No. That’s what happened. It’s water under the bridge now. Who cares, anyway? Nobody really cares. The Zeppelin fans don’t want to hear anything to spoil their life-long belief that they are the greatest band ever, you know.

Did that prevent you from being a fan of Zeppelin in some ways?

Yeah, it did. Not only that. I’d just had the Devil’s own job thinking what I was gonna do, and that added to the frustration of not being armed and ready. I was ready mentally to play and blow everybody away, but I didn’t have a bass player or drummer.

Do you still keep in touch Page and Clapton?

No. I see Eric from time to time, but very rarely.

How do you look back on BBA, when you finally managed to get together with the rhythm section of Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice?

We were really good, the three of us. Unfortunately, it was too much like a very commercial version of Cream, with songs. There’s nothing quite like a power trio. You don’t have any chords backing the solos, you’ve just got the drum groove and the bass going. Fantastic. Look at Hendrix – he didn’t do bad, did he?

You’ve had a long and varied career so far, doubtless filled with memories both good and bad.

It’s been a rough road. I never got to the point ever where I thought I’d actually achieved anything. Which I suppose is why when George Martin agreed to do the two albums [Blow By Blow and Wired, ’75 and ’76] I took that very seriously, because he’s such a genius. I think if I look back over 30 years, you would have to say that George was the one who actually recognised my potential and put it on record better than anybody else has. Unfortunately I wasn’t about to be stuck in a rut with George. I didn’t feel that happening, but I wanted to move on with Jan [Hammer, keyboard player], and make sure it didn’t happen. Comfy shoes was not something I wanted.

Are there any career decisions that you wish you could go back and change?

All of them [laughs]. I think – and without decrying anything about the players – it would be the Cozy band [the Mk II version of The Jeff Beck group, with Cozy Powell on drums]. That was a mistake. I was just recovering from a car crash. It wasn’t severe, no brain damage or anything, and I wasn’t incapacitated for more than about three months, but going back into a room full of people playing loud noises was a horrible experience. And I never realised I was being coerced into playing songs that I wouldn’t be looking at normally. I just wish that album [Rough & Ready, 1971] would go away. Awful. But people still bring out the bloody thing on CD and reissues and bootlegs.

When did you really start to find a direction again?

When I started taking myself a bit more seriously. About 1973. I realised that I could lose what I’d got, to the point where I don’t make anything substantial to keep me going. I turned up at George Martin’s office with a diabolically bad demo, but he could see there was something there.

What kind of music do you listen to now?

Lots of stuff. I try to listen to the radio, but it’s impossible. I can’t bear the sound of their voices, never mind the music they play. And anyone who talks over a record should be shot. They keep interrupting, and fading the song and talking some gibberish, and it’s insulting in the extreme. I’m out gunning for those bastards [laughs].

I see the whole musical world and general public life as a big circus that I’m not involved in – thank God. Somebody tried to put me down once by saying: “Jeff was the leader of the parade once, and now he seems to be content to watch it go by.” I wote back and said: “You got that spot-on. I’m absolutely happy to watch it go by.”

Did you go to see any of the Cream reunion shows at the Albert Hall last year?

No. They had the good sense not to put me on the guest list. But I did go to the party. Fantastic! I’d go to see Prince again though. And Robert Plant was good recently.

Can you think of two or three albums that will always be in your Top 20?

All of Django’s [Reinhardt, guitarist] works. I dunno, er… Oh, Billy Cobham’s Spectrum. That’s a real milestone album. Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds Of Fire, and From Nothingness To Eternity, live, is a fantastic album. That’s the Central Park gig that they did.

Are there any new bands or new instrumentalists who have impressed you?

Well, I like the way Robert Randolph plays. He’s a lap steel player. He’s wicked; real raving blues stuff on lap steel. But there’s not much at all, really. I listen to Asian dub stuff. I used to listen a lot to an Asian station called Sunrise Radio, but it’s got a bit bland now. About five or six years ago they were playing really ground-breaking stuff; fantastic traditional Indian stuff. The grooves were there, really danceable. It was like the Chemical Brothers meets… all kinds of stuff going on. But now it’s sort of Westernised, very samey stuff. There’s a couple of Asian stations that I listen to just to get away from the unbearable blandness and phoniness of all the other stations.

You’re very much an inspirational player; nine out of 10 of your gigs might be good, but then one will, for whatever reasons, be exceptional. What makes the difference?

Tiredness, sound problems, it’s a combination of things. Sometimes just the spatial disorientation of being out on the road will prevent the ultimate performance. And then when it all clicks together and you’re feeling great and the sound’s great… It’s the sound that drives me. From first go, when you count off, I know exactly where it is.

Are those nights, when it all falls into place and you’re really on one and absolutely nail it, that makes it all worthwhile?

Oh yeah. And you know when you’ve done it. The feeling you get when you know you’ve flattened the place… You almost feel guilty.

Does it get increasingly difficult to dig deep and bring out whatever it is that enables you to really deliver night after night?

Not really. The thing is, the reason we’ve got these songs in the set list is because they are demanding, and people see the effort and the skill that goes into playing them.

What do you get from playing live?

Time speeds up, that’s one thing. The hour-and-a-half is like 15 minutes. Time goes by mighty quick when you’re in danger. You’re in constant danger on stage. There’s a certain amount of seat-of-the-pants risk all the time. And apart from driving hot-rods with dodgy brakes there’s no other thrill like it [laughs].

This business is flooded with rubbish and wannabes, because it’s a great place to be. It’s the best job you can have. No wonder there are millions of people wanting to be in it. So much of it is just about celebrity. You get people outside radio stations asking: “Are you famous, mate? Can I have your autograph?” If they have to ask, you’re not famous, are you?!

This interview originally appeared in Classic Rock 102, published in February 2007.