The US Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Roe v Wade affirmed constitutional protections for abortion access through a right to privacy enumerated in the 14th Amendment’s “due process” clause, written in the Reconstruction-era aftermath of the US Civil War.

Abortion rights advocate Merle Hoffman has argued that the legal defence of abortion care should instead look to the 13th Amendment – which abolished slavery.

“If you’re forcing someone to carry a child against their will, and you are really owning their bodies, which is what it is, I don’t know what else you would call that,” she tells The Independent, speaking before the Supreme Court’s June 24 decision to end constitutional protections for abortion care. “And then look at what happens when somebody lives in Texas, and then they close the doors there, and then they say, ‘Oh, well go to Oklahoma.’”

Last year, Texas banned abortions at six weeks of pregnancy, before many people know they are pregnant, and below the 22- to 23-three-week threshold of fetal viability established under Roe. The Supreme Court refused to intervene in legal challenges to block the law, emboldening other states – like neighbouring Oklahoma – to pass similar and more-restrictive laws, growing the nation’s patchwork of criminal abortion statutes that threaten bodily autonomy protections for millions of Americans.

The leaked draft opinion written by conservative Justice Samuel Alito in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case involving a Mississippi law banning abortion at 15 weeks of pregnancy, revealed the court’s readiness to overturn Roe entirely – as it subsequently did on June 24 – ending all federal protections for abortion care and triggering a wave of anti-abortion laws in roughly half the US.

“I was not surprised,” Ms Hoffman tells The Independent. “I’ve had friends murdered … It’s a war, and I’ve been on the front line of it for many, many years.”

David Gunn, an obstetrician and abortion care provider, was fatally shot in Pensacola, Florida by an anti-abortion fundamentalist Christian activist in 1993. Kansas physician and abortion care provider George Tiller was murdered by an anti-abortion extremist at Tiller’s church on a Sunday morning in 2009.

More than a decade later, the Queens, New York clinic that Ms Hoffman helped open more than 50 years ago still faces ongoing obstruction from anti-abortion activists outside its doors.

“It’s been ongoing, but it’s been escalating and escalating,” Ms Hoffman says

An influential Christian conservative movement alongside a so-called “pro-life” movement to oppose abortion rights in the decades after the Roe ruling has fortified a political and cultural opposition to abortion care, manipulating the public dialogue about abortion rights that ignores the rights of pregnant patients, Ms Hoffman argues.

“The opposition has done a really brilliant job of defining the narrative,” she says. “These people are soldiers of the lord, and they’re not stopping. … They think in biblical terms.”

In 1970, three years before the Supreme Court’s decision in the Roe case, New York was among a handful of states to repeal its anti-abortion laws.

At the time, Ms Hoffman was a graduate student studying psychology and working inside a doctor’s office. One year later, she helped open Flushing Women’s Medical Center, which would become Choices Women’s Medical Center, one of the first abortion clinics in the country. The centre offers a range of healthcare services.

Her practice developed what have become patient-centred standards for abortion care, providing emotional support, informed consent and other reproductive health services in a field that Ms Hoffman found was driven by largely patriarchal and paternalistic attitudes towards patients.

Ms Hoffman remembers holding the hand of one of the clinic’s first patients, a white Catholic woman with three children from New Jersey. Over the years that followed, the clinic saw more and more patients traveling longer distances to find legal care after their states restricted access to abortions.

In 2022, a wave of anti-abortion legislation in Republican-led states anticipating the Supreme Court’s decision proposed eliminating abortion access in most cases and criminalising abortion care by making it a felony for providers to see abortion patients.

But in the years after the original Roe decision, state legislators imposed other obstacles to abortion access, including requirements for ultrasounds, state-directed counseling and waiting periods, bans on the use of certain health insurance to cover abortion care, and bans on telemedicine appointments to obtain prescriptions for medication abortion, the most common form of abortion.

“You personally can be very anti-abortion. … But if you say, ‘I would never have one, and I want to make sure that no woman or girl in this country does either’ – that’s a big difference,” Ms Hoffman says. “It’s such a profound, intimate decision, that I would not even attempt to think about making that choice for anybody else.”

Roughly 62 per cent of American women live within 10 miles of an abortion clinic. Under state-level bans without Roe protections, that figure will be cut nearly in half. The typical median distance a patient would have to travel to access an abortion provider would nearly triple – from roughly 39 miles to 113 miles. In some states like Louisiana and Mississippi, patients will have to travel more than 800 miles to the nearest legal provider.

Ms Hoffman anticipated more patients would travel to New York and other states that protect abortion after the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dobbs case, while clinics and a network of abortion fund groups and organisations that help with housing and travel will absorb more patients and care for a larger pool of patients.

“This is going to be not only on the clinics, but it’s going to be a major stressor on the hospitals, on the healthcare system – on everything,” Ms Hoffman says.

It wasn’t the 1973 Roe decision that galvanised Ms Hoffman’s political action and decades-long advocacy for abortion rights – it was the passage of the Hyde Amendment in the aftermath of Roe.

The Hyde Amendment prohibits the use of federal funding to support abortion care, dramatically limiting access for people on Medicaid – the federal healthcare programme for lower-income Americans – and other federal health programme. The amendment is not permanent law but a legislative provision or “rider” attached to a congressional appropriations bill each year.

Its adoption in wake of the original Roe ruling “really emphasized the class-race distinction” for abortion access, Ms Hoffman says.

After the amendment’s introduction in the late 1970s, Ms Hoffman returned to the campus of Queens College “enraged”, knocking on teachers’ doors and demanding to talk with students about the Hyde Amendment’s threats to abortion care.

“There’s a crisis here,” she told them.

The students were largely apathetic, she says, “and the attitude was, ‘well, I can always get my abortion.’”

In the decades that followed, congressional lawmakers and presidential candidates have relied on the Hyde Amendment for political leverage – former president Barack Obama preserved its language to ensure passage of the Affordable Care Act.

“I am just sick and tired of women’s lives and women’s freedom being a political football kicked back and forth,” Ms Hoffman tells The Independent. “And this is why so many Black women or minority women talk about reproductive justice, and feel that [the abortion rights movement] is this business of reproductive rights as a white woman’s struggle. Well, it’s all of our struggles, but we weren’t there for them.”

Ms Hoffman has criticised what she believes are the failures of national, high-profile abortion rights advocates and members of Congress to take a radical anti-abortion movement seriously and push for stronger abortion protections at the federal level.

Instead, they have relied on a vulnerable Supreme Court ruling to uphold abortion rights while Democratic officials – even with majorities in Congress and control of the White House – repeatedly fail to codify those protections into law.

“I have always felt that the ‘pro-choice’ movement minimised the opposition by diminishing them,” Ms Hoffman says. “And as a result, we have the Hyde Amendment … And that’s when all hell should have broken loose, but it didn’t.”

The leak that preceded the June 24 ruling offered the abortion rights movement a “major wake-up call” to the erosion of abortion rights and the fragility of abortion care protections at the federal level, she says.

“It’s become more real. And I live in reality,” she says. “The ‘pro-choice’ movement put their metaphorical feet up on the desk politically.”

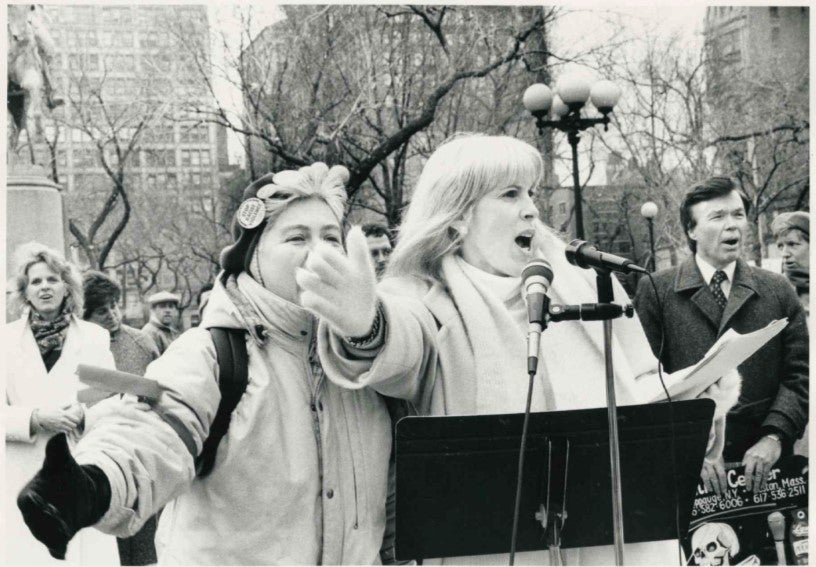

In January, she formed Rise Up for 4 Abortion Rights with activists Lori Sokol and Sunsara Taylor, channeling “a feeling of rage” into mass protests, student walkouts and demanding a sustained and nonviolent movement to stop the Supreme Court from gutting abortion rights and pressuring legislators to protect them.

“I’ll be damned if I’m going down without a fight,” Ms Hoffman says.