Last week, UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng launched a bid to boost economic growth with the largest tax cutting exercise for half a century. What this so-called mini-budget has since overshadowed, however, was an admission by the Bank of England the previous day that the UK may already be in a recession.

The fact that this statement from the UK central bank has been lost amid news of a plunging pound and general financial market volatility is no surprise, but it also speaks to the difficulties in trying to pin down whether or not an economy has actually entered a recession.

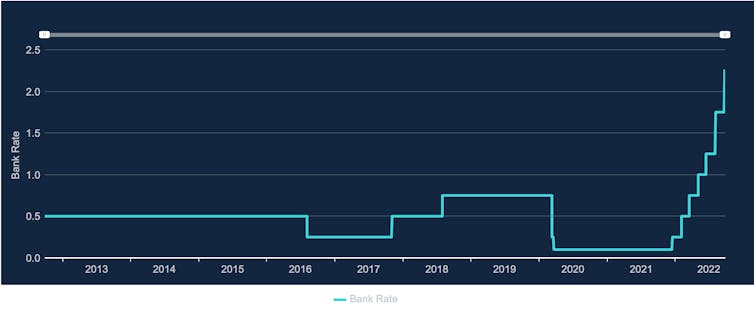

On September 22, five out of the nine members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to increase the base rate by 0.5% to 2.25%. This is the rate banks and lenders pay, which in turn influences the interest rates people pay for mortgages and savings products.

It is now at the highest level since the 2007-2008 global financial crisis. The Bank has been steadily working up to this point since its December 2021 meeting and more hikes are expected as it attempts to bring soaring inflation back towards its 2% target.

UK base rate changes, 2013-2022

The MPC also releases minutes of its meetings, which most recently included a warning about the UK economy entering – or possibly even already being in – a recession. More precisely, the Bank expects gross domestic product (GDP) to fall by 0.1% in the current quarter (Q3), well below it’s August projection of 0.4% growth.

More worryingly, this would constitute a second successive quarterly decline, based on preliminary data released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for the second quarter of this year.

The lack of certainty from the central bank indicates the difficulty of spotting and agreeing on recessions because there isn’t a universal definition. Wikipedia, for example, was forced to suspend edits to its page on recession in July after a debate erupted over changes to the definition. The entry now reads:

Although the definition of a recession varies between different countries and scholars, two consecutive quarters of decline in a country’s real gross domestic product (real GDP) is commonly used as a practical definition of a recession.

So, the general consensus seems to be that GDP data pointing consistently to a reduction in economic activity should be interpreted as bad news because the economy is thought to be shrinking. This is normally associated with a decrease in consumer spending, a decline in business confidence and a consequent increase in unemployment.

Certainly, any sign of a downturn typically sees banks and financial institutions tightening their lending criteria, making it difficult to obtain mortgages and business financing. This affects the housing market and small business activity.

Further, since economies do not normally bounce back immediately from a recession, a period of prolonged depressed economic activity could lead to long-term unemployment, affecting people’s chances of future employment and earnings growth, especially younger generations and those from low-income households. This phenomenon is known as “employment scarring”.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that the Bank of England is ringing the recession alarm bell even before it has full confirmation. But even with an agreement on a definition of sorts, measuring the state of the economy – that is, judging whether a country is in a recession or expansion – is not as straightforward as you might imagine.

Firstly, the data or projections being released by the Bank of England, the ONS and more generally by other institutions around the world are “preliminary” – especially when first published for the relevant quarter. This means this data could be subject to subsequent revisions.

For instance, in September 2022 (the final month of the third quarter) available data may indicate the economy has shrunk in the third quarter. However, as more information about Q3 performance is gathered, by October or November 2022 this negative growth sign might revert to zero growth or even positive.

This is called “real-time data uncertainty” and it is one of the challenges policymakers face when making decisions “in real time”. In other words, central banks make decisions based on an evolving and often “noisy” understanding of the state of the economy.

Secondly, as US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen also commented recently, negative growth associated with otherwise strong labour market conditions and spending, should not necessarily imply bad news for the economy. What she means here is that GDP should not be the only indicator on which an economic assessment is based – a broad range of indicators can often provide a different picture.

The outlook for UK growth

So, what is the Bank of England’s current assessment of the state of the UK economy? The minutes from its most recent meeting say: “The expected slowing in underlying growth in 2022 Q3 was consistent with weakness documented in the latest business surveys.”

These business surveys indicate close to zero near-term growth, while an important indicator of expected business activity (called the composite purchasing managers’ index output expectations series) fell between June and August 2022.

The Bank also said weak growth in manufacturing output (due to supply chain disruptions) and weak demand is adversely affecting the economy. Meanwhile, business investment intentions have been reported as weakening, with firms citing uncertainty about demand and the broader economic outlook, as well as rising costs, as the main drivers of a decline in investments.

So the Bank of England is painting a picture using a multitude of indicators to show a shrinking economy. In this context, the Bank has said it will closely monitor upcoming data, as well as the evolution of Kwarteng’s growth plan policies set out on September 23. It will hope the latter can give a non-trivial boost to a seemingly deteriorating economy.

Luciano Rispoli does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.