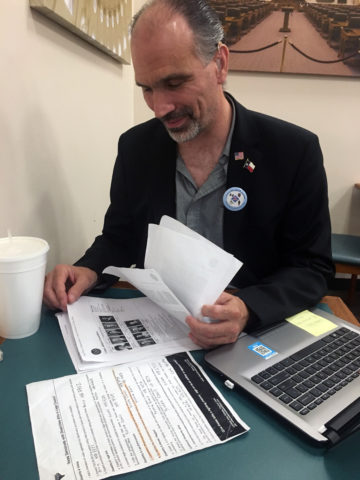

John Woodley pushed a wheelchair through the Capitol almost every day this session, his files and laptop piled on the seat. At age 2, he developed partial deafness and can only hear low-pitch vowel sounds. A 2013 car crash left him unable to walk long distances or lift more than a couple of pounds.

While that didn’t stop him from visiting lawmakers’ offices to advocate for disability rights this session, Woodley says that the Capitol staff’s refusal to provide accommodations he requested under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) impeded his ability to participate in the legislative process.

“I’m missing the larger part of the alphabet,” Woodley said. “I can’t walk very far, I can’t run, I can’t carry very much, so I have to use assistive devices to help me.”

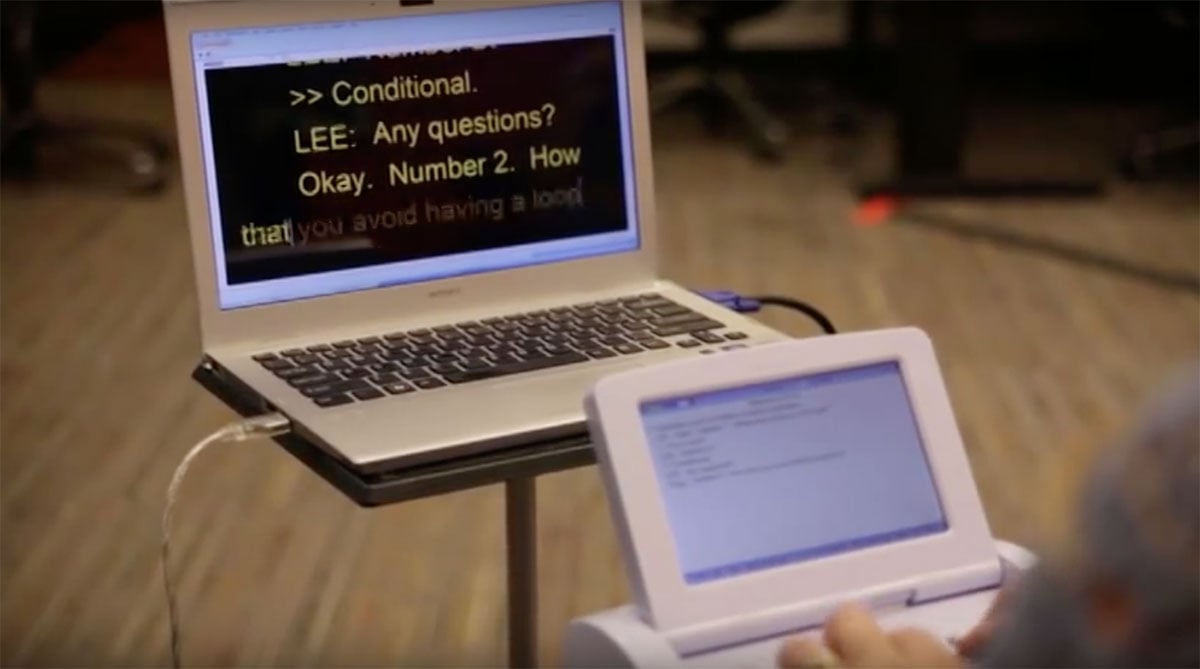

Woodley relies on a form of closed captioning known as communication access real-time translation. It requires another person to listen to an event and transcribe the discussion in shorthand. A computer translates the shorthand into words the user reads on a portable screen.

Woodley said he has been able to secure the service in county and city government meetings in Austin. But when he repeatedly asked for the captioning service for legislative hearings this year, his requests were denied, records show.

“Most people, if they need to follow up on a hearing, they can just go online and watch the video, but I don’t have that opportunity,” Woodley told the Observer.

Woodley’s first emailed request for captioning this session was on April 14, a Sunday, for hearings on 14 bills. James Freeman, a payroll, personnel and ADA coordinator for the House, responded to Woodley the next day, asking him to specify each individual hearing and requesting at least 72 hours of notice for ADA requests. Woodley responded the same day with a request for captioning of a single hearing on April 18.

“Right now, our policy provides that we can provide interpreter services to accommodate those who are deaf or hearing impaired,” Freeman wrote back on April 15. In the same email, Freeman offered Woodley an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter or an FM assistive listening device, which amplifies sound.

Those options “do not help me. I need [communication access real-time translation],” he told Freeman in another email a few minutes later.

In an interview with the Observer, Woodley explained why the other two options don’t work for him. “Not everybody who is deaf knows ASL. Some may know some sign, others maybe never learned sign language,” Woodley said. Since his deafness is not volume-specific, he said FM listening devices that amplify sound don’t help him either.

On April 17, Freeman wrote back to tell Woodley that his request for the individual hearing was denied, emails show. The request for captioning “was not reasonable or feasible,” Freeman wrote, citing unspecified costs and “the difficulty in coordinating live (ever-changing) events.

“These accommodations have been provided to many deaf, deaf-blind or hearing impaired advocates and other members of the public and have proven to be very helpful,” Freeman wrote. “We believe our current options for interpreter services and/or FM assistive listening devices are sufficient to provide meaningful access to the legislative process.”

His request was denied.

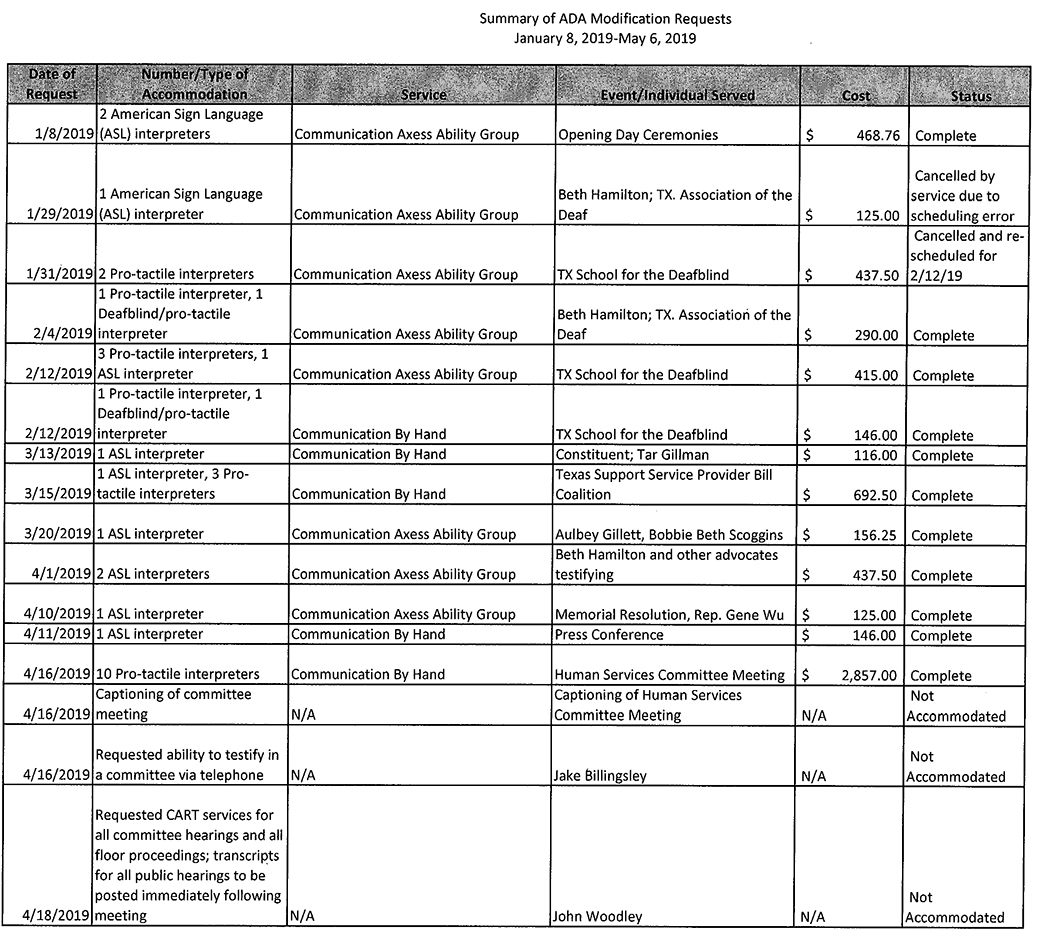

Records obtained by the Observer show that 11 ADA accommodations were filled this session in the House, while three were denied. The requests filled were all either for pro-tactile interpreters, who translate words into touch for deaf-blind individuals, or ASL interpreters, at costs ranging from $125 to $2,857 each. Two of the three denied requests listed were for captioning.

“They provide accommodations for some disabilities but not others,” said Joey Gidseg, chair of Texas Democrats with Disabilities. “It’s really discriminatory.”

Molly Broadway, a voting rights compliance expert for Disability Rights Texas, said the ADA is intentionally broad and open to interpretation, but explicitly states that governmental entities should give primary consideration to the requestor’s preferred way of accessing proceedings.

William Goren is an Atlanta attorney and ADA consultant. He said the Capitol “is going to have to [provide captioning] unless they can show the accommodation is going to financially destroy them or turn their operations upside down. If they don’t, they are going to have to show that it creates an undue burden. And that’s a case they would lose.”

The House’s decision to refuse to offer some accommodations while always offering others may violate the ADA, according to Goren, who said offering a set list of accommodations is “a recipe for disaster.”

Freeman did not respond to a request for comment.

A bill filed this session by state Representative Victoria Neave, D-Dallas, would have required captioning of all governmental meetings, but it did not get a hearing. However, a budget rider successfully tacked on near the end of the session includes language encouraging — but not requiring — the Legislature to caption future video broadcasts of open meetings. The Oklahoma Legislature began captioning all proceedings after a man who is deaf filed suit against the state in 2015. A similar lawsuit is moving forward in Florida.

–

Woodley isn’t the only advocate who believes his rights were potentially violated at the Capitol.

Jake Billingsley, who suffers from brain damage caused by a stroke, contacted Freeman on March 25 with a request to testify in a committee hearing via telephone or video, rather than in person, on a bill that would help people with disabilities obtain legal services, emails show.

“I can perform at exceptional levels on the phone, discussing things with people,” said Billingsley, who added that he is almost entirely homebound. “But going to the Capitol to give cogent witness testimony and response would be a stimulus and cognitive overload for me.”

Billingsley’s request was forwarded to House Committee Coordinator Stacey Nicchio, who asked in an email on March 27 whether Billingsley would be willing to have someone read his testimony on his behalf. He declined because it “would not allow interaction with committee members to ask questions.”

Three weeks later, on April 17, Billingsley says he received a phone call from Gardner Pate, director of policy and general counsel for House Speaker Dennis Bonnen. Pate told Billingsley that if he testified via telephone and it was found to be outside the House rules, his testimony could kill the legislation through a parliamentary procedure, according to Billingsley. Pate promised to look into the House rules.

Billingsley wrote back to Pate that “not being allowed to interact by giving testimony” made him “[feel] like the ‘vegetable’ isolated and relegated to the corner of the room.”

In an email to Billingsley on May 8, Pate said he found that testifying via video conference is in fact acceptable under House parliamentary procedure. But by that time — more than six weeks after Billingsley’s initial request — the hearings in which he sought to testify were over. His request was listed as denied in the records obtained by the Observer.

Pate didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“[Jake Billingsley has] effectively been locked out of the process,” said Gidseg. “Not allowing him to speak on something, especially when his testimony would go so far, hurts [our efforts] and the people we’re trying to help.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect a budget rider passed near the end of the legislative session that encourages, but doesn’t require, the Legislature to caption future video broadcasts of open meetings. This story also initially reported that John Woodley was born with partial deafness. In fact, he developed partial deafness at age 2.