For three years now, I’ve been regularly visiting a special corner of the Internet — the digital library of former Attorney General K.K. Venugopal. In March 2020, Venugopal decided to digitise and upload his extensive collection of antiquarian books — a process that took, for the first lot of nearly 1,200 books, half a year. Today, the collection has almost 1,900 books, and waiting in the wings are thousands more.

Venugopal began collecting books in 1970, starting with a title on the erstwhile South Indian Railway Company. He hasn’t stopped, and when I visit him, he shows me a new auction catalogue he has his eyes on. The books on the website, www.kkvlibrary.com, are copyright free and can be downloaded, too. The oldest in the collection is a travelogue: Travels In Hindustan: The History Of The Late Revolution Of The Dominions Of The Great Mogol by Francois Bernier, dating back to 1676. In fact, historical travelogues are one of the biggest segments in Venugopal’s library — accounts of visitors to the country, mostly men, but also a few women — who turned their lens on India.

By the 18th century, Indians too were writing travelogues, and in 1790, the first account written in an Indian language was published — Varthamanappusthakam, by the Malayali Syriac Christian priest Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar. In English, The Travels of Dean Mahomet by Dean Mahomed, a native of Patna, was released in 1794 — the first English book to be published by an Indian. Later, through the 18th and 19th centuries, more Indians would write accounts of their travels to far corners of the world — Russia, China, Africa, the U.S. and Europe.

The depictions by early visitors to India are both fascinating and evocative — a product of the colonial lens and in several cases, an anthropological study of a people and a land so expansive, changeable and new to foreign eyes. Today, these accounts act like windows into a different time, both alien and familiar. We bring to you a few snippets from some of these books — portraits of people, places, and the past.

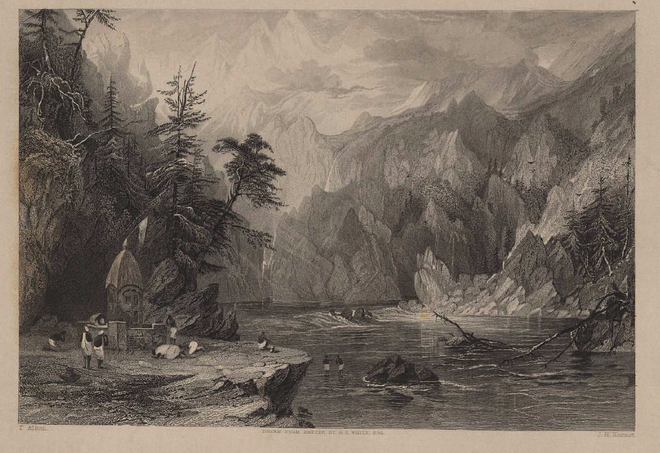

The Ganges

“The Ganges, at this place, abounds with fish of all kinds; and, amongst them, the king of the finny tribes, the noble mahaseer, or great-head, which by many persons is esteemed the most delicious fresh-water fish which ever gratified the palate of an epicure. It rises to the fly, affording excellent sport to the angler, sometimes attaining the size o f a large cod, and is taken with considerable difficulty, even by those who have been accustomed to salmon-fishing in the most celebrated rivers of Scotland. The mahaseer is sent to table in various ways, Indian cooks being famous for their fish-stews and curries ; but it does not require any adventitious aid from the culinary art, as it is exquisite when plain-boiled, being, according to the best gastronomic authority, luscious but yet unsatiating.”

— Views In India, Chiefly Among The Himalaya Mountains; Lieut. George Francis White, of the 31st Regt. (1836)

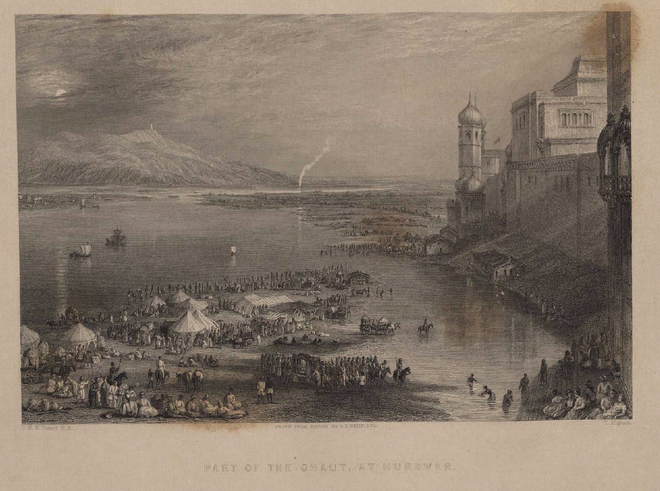

Haridwar

“A fair takes place annually at Hurdwar in the month of April, lasting nearly a fortnight, that being the period chosen by the pilgrims, who flock from all parts of India, to perform their ablutions in the Ganges… The climate of Hurdwar during the early part of April is exceedingly variable: from four in the afternoon, until nine or ten o’clock on the following day, the wind generally blows from the north or east over the snowy mountains, rendering the air delightfully cool; during the intermediate hours, however, the thermometer frequently rises to 94°; and the clouds of dust arising from the concourse of people, together with their beasts of burden, collected at this place, add considerably to the annoyance sustained from the heat.”

— Views In India, Chiefly Among The Himalaya Mountains; Lieut. George Francis White, of the 31st Regt. (1836)

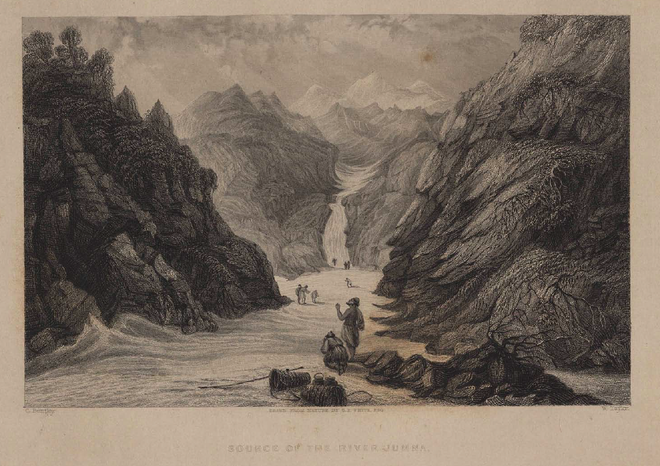

The Yamuna

“As we approached Jumnootree, which is not accessible until the month of May, we found the river gliding under arches of ice, through which it had worn its passage, and at length, these masses becoming too strongly frozen to yield and fall into the current, the stream itself could be traced no longer, and, if not at its actual source, we stood at the first stage of its youthful existence… The most holy spot is found upon the left bank, where a mass of quartz and silicious schist rock sends forth five hot springs into the bed of the river, which boil and bubble at a furious rate. When mingled with the icy-cold stream of the Jumna, these smoking springs form a very delightful tepid bath, and the pilgrims, after dipping their hands in the hottest part, perform much more agreeable ablutions.”

— Views In India, Chiefly Among The Himalaya Mountains; Lieut. George Francis White, of the 31st Regt. (1836)

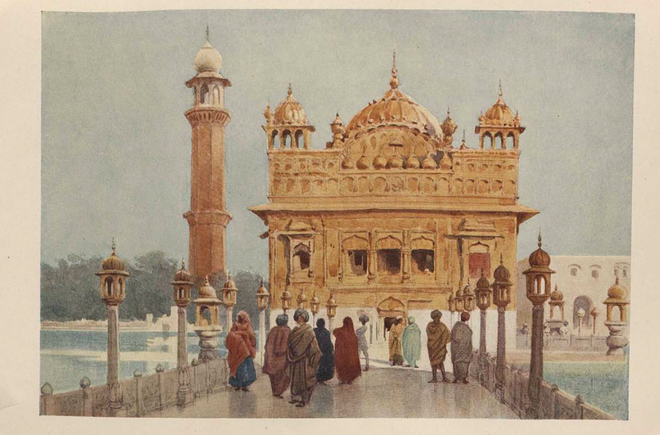

Amritsar

“Nothing, however, that I have ever seen can compare with the Golden Temple, in its own particular way, and it is quite as impossible to describe adequately its towers and minarets and other sacred spots and things, in and around its precincts, as it would be to describe a beautiful dream. The whole thing is like a dream, too strange and in some ways too beautiful to describe.”

— The High-Road Of Empire; A.H. Hallam Murray (1905)

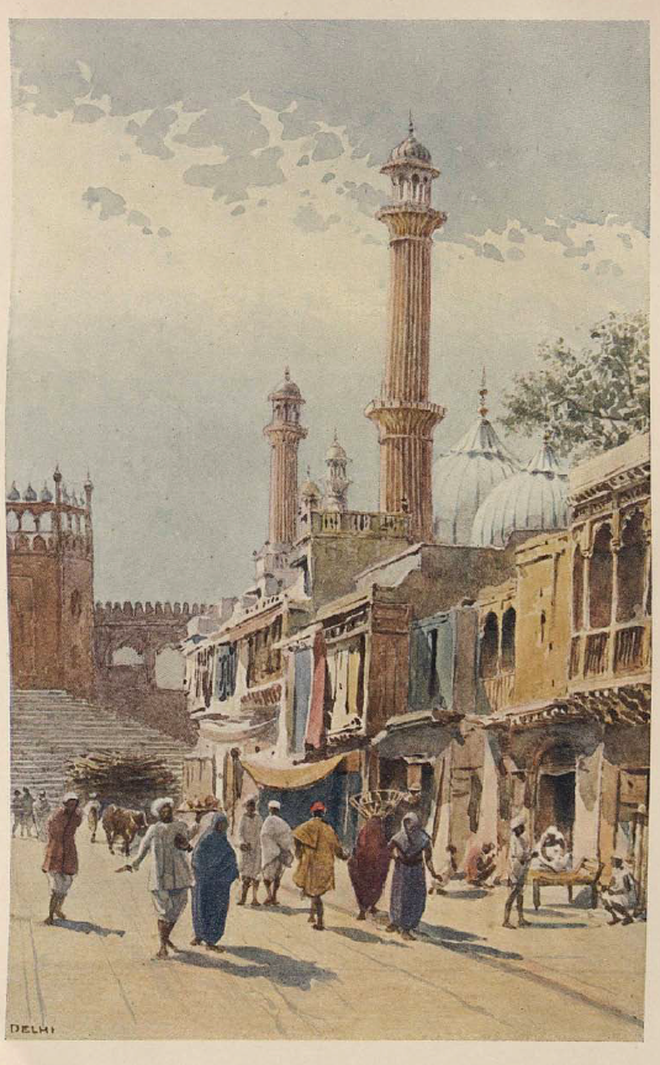

Delhi

“As a city it has marked features of its own. Unlike the other cities I had visited, it is walled, and that too… in a most substantial manner — thanks to our own engineers. Although there are many streets as tortuous and narrow as are found in other towns, I did not see anywhere that squalor and tumble-down confusion which arrest the eye in the native quarters of Bombay or Calcutta; while one leading thoroughfare, the Chandnee Chouk, leading direct from the Lahore Gate to the Palace, is really a fine street, ninety feet wide, about a mile long, with a row of trees, a canal along its center (covered, except in a few places), and with comfortable-looking veranda-houses and good shops on either side.”

— Days In North India; Norman Macleod (1870)

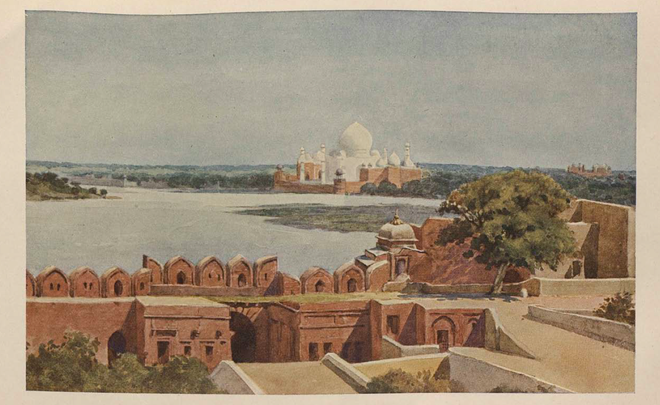

Agra

“Books have given everyone a certain amount of general information regarding the Mohammedan conquest of India under Baber in the fifteenth century... But I had never before seen anything... that gave me any true idea of Mohammedan architecture. In Agra we were as in a new world... a splendid exotic flowering in beauty and brilliancy... The famous Taj, the gem of India and of the world, the Koh-i-noor of architecture, is situated about three miles from Agra, on the west bank of the Jumna... We were conducted to the upper story, and from a great open arch beheld the Taj! All sensible travelers here pause when attempting to describe this building, and protest that the attempt is folly, and betrays only an unwarranted confidence in the power of words to give any idea of such a vision in stone. I do not cherish the hope of being able to convey any true impression of the magnificence and beauty of the Taj, but nevertheless I cannot be silent about it.

— Days In North India; Norman Macleod (1870)

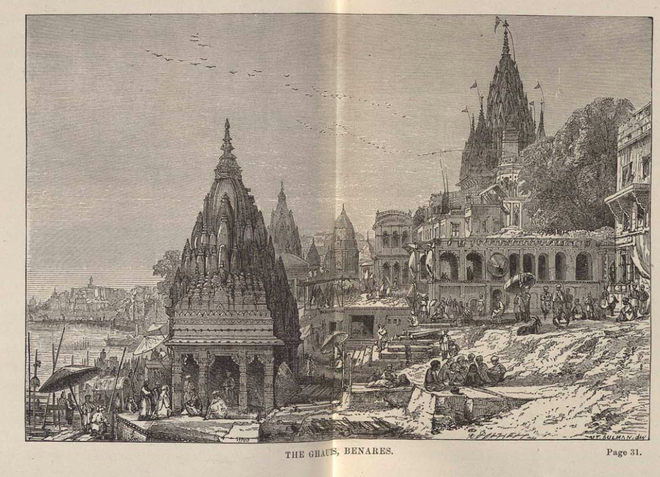

Benaras

“In its structure internally as a city, as well as in other respects which I shall presently allude to, Benares stands alone. The houses are all built of solid stone, obtained from the quarries of Chumar in the immediate-neighborhood. They are flanked by houses six or even seven stories high. Whether to gain shade from the burning sun, or as a means of defense against foes, these streets are so narrow as to resemble the closes in the old town of Edinburgh. Indeed, if our readers can suppose the closes worming through the whole city with sharp turnings and endless windings, they will have a pretty good idea of the place. There are shops of every kind and for every trade, according to the quarter of the city. All these are open to the street. There are workers in brass and iron, in silver, gold, and jewels; workers of slippers and saddlery; of arms and accoutrements; of cloths and Oriental fabrics; of sweetmeats ad nauseam; and sellers of grain of every kind.”

— Days In North India; Norman Macleod (1870)

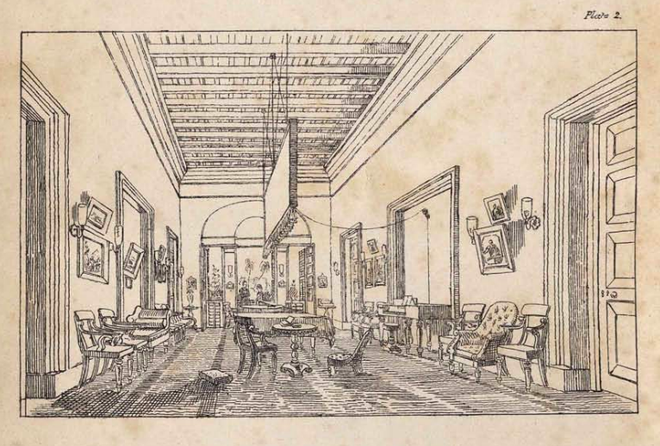

Calcutta

“Permit me, then, in greater form, to introduce you to the exterior of the house… a comfortable, well raised, lower-roomed dwelling… The rent of such a house you will doubtless consider exorbitant, being seventy roopees per month. Rent in Calcutta is indeed extremely high, but there are no taxes on the tenant.

The houses of Calcutta are of all shapes, ranging through the whole table of geometrical figures… but however big — and some resemble castles… you are aware our city is called the “City of Palaces,” their internal arrangements differ but little, consequently, in describing one, I describe all, though upon a larger or smaller scale as the case may be.”

— An Anglo-Indian Domestic Sketch: A Letter from An Artist in India to His Mother in England (1849)

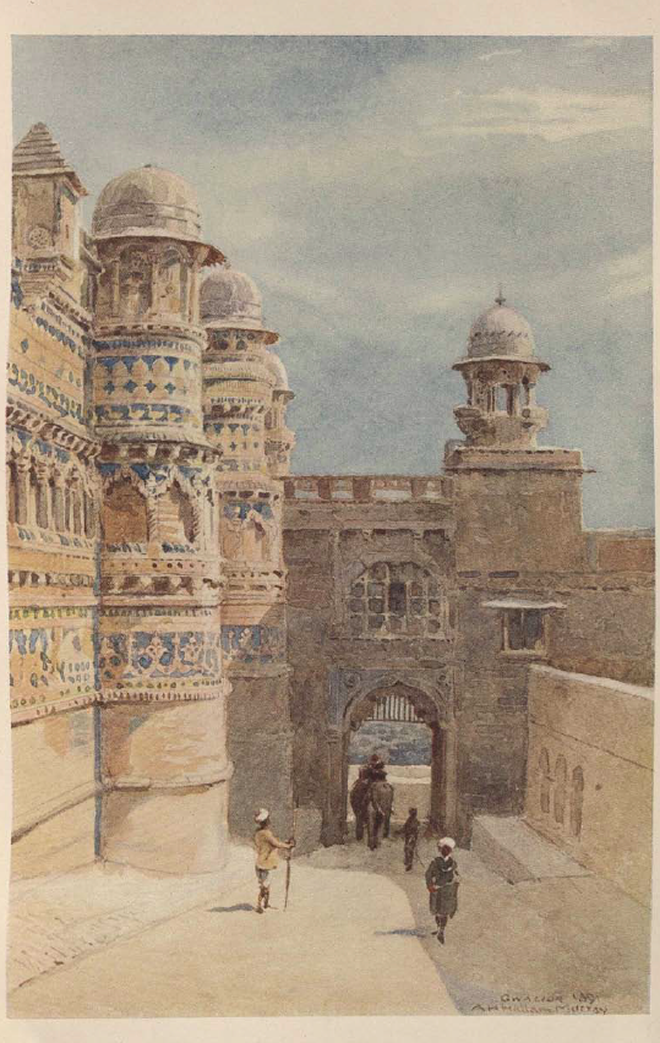

Gwalior

“It is an immensely steep, hot climb up to the top of the rock on which stands the Fort and palaces; but the elephant took us up leisurely, under the guidance of a good-looking Sikh of the Maharaja’s troops, and a policeman and two mahouts; and we had time to admire the little Jain and Buddhist carvings on the rock, and the view, constantly widening out across the plain, as we went along, under six grand gateways and past many small temples. There was one temple, about fourteen feet high, pinnacles and all, carved out of one stone most elaborately, about the year 800, in the days when our forefathers were more concerned with feeding their pigs on acorns than architecture.”

— The High-Road Of Empire; by A.H. Hallam Murray (1905)

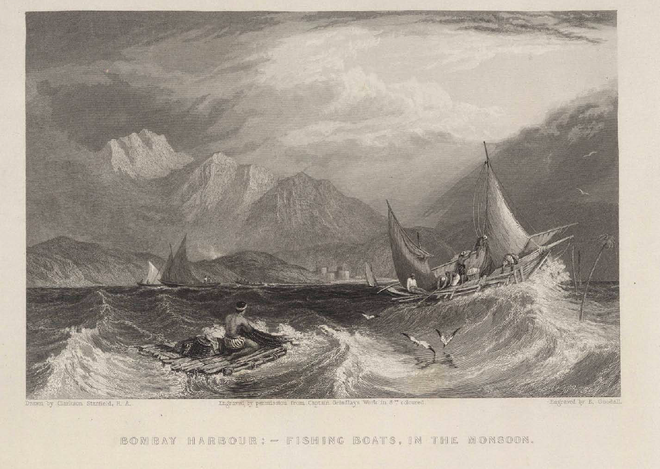

Bombay

“The Harbour of Bombay presents one of the most striking and beautiful views that ever delighted the eye of a painter… During the best season of the year, the water is smooth, while the breeze blowing in from the sea through the greater part of the day, the very smallest boats are, with the assistance of the tide, enabled to voyage along the beautiful coast, or to the various islands which gem the scarcely ruffled wave… Even during the monsoon, when many other places of the Indian coast are unapproachable, when the lofty and apparently interminable mountains which form the magnificent back-ground are capped with clouds, and the sea-birds that love the storm, skim between the foam-crowned billows, the fishing-boats breast the waves, and pursue their occupation uninterruptedly.”

— Views In India, Chiefly Among The Himalaya Mountains; Lieut. George Francis White, of the 31st Regt. (1836)

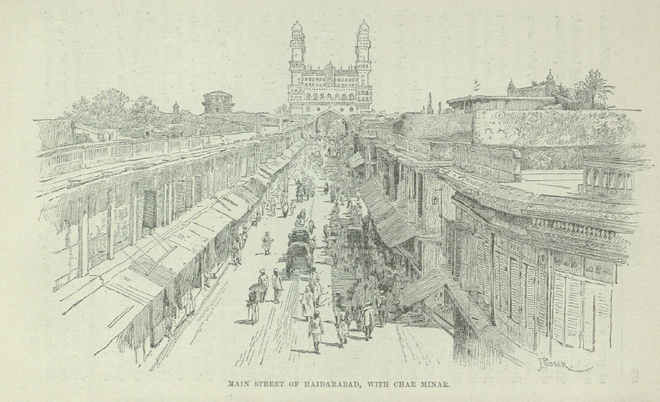

Hyderabad

“In the very centre of the city, at the junction of the four main streets, is the famous Char Minar, or four towers, built about a.d. 1600, upon four grand arches, above which are several storeys of rooms originally devoted to a college but now used as a store-house. The building is four, square, each face being 100 feet, and the minarets soar into the air 250 feet above the level of the street. This is the busiest spot in the whole city, and hours may be spent watching the amusing and picturesque scenes surrounding the Char Minar.”

— Picturesque India; W.S. Caine (1890)

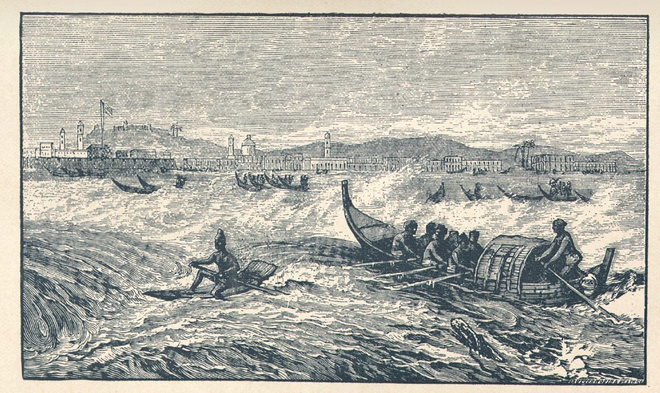

Madras

“The drive along the beach to the Capper House is the pleasantest in Madras. Here one meets the sea-breeze, appropriately called by the residents “the doctor”. Here we pass the most imposing of the public buildings of the city, in particular the University. It was strange to see on the Sunday the punkas swinging during service in the churches.

Like huge weavers beams with heavy curtains, they are kept in motion by means of cords pulled from the outside, two natives, who keep each other awake, being employed for everyone. However strict a Sabbatarian, the minister as well as the people must have the punka kept going over his head throughout the service.”

— Indian Pictures; Rev. W. Urwick (1891)

Madurai

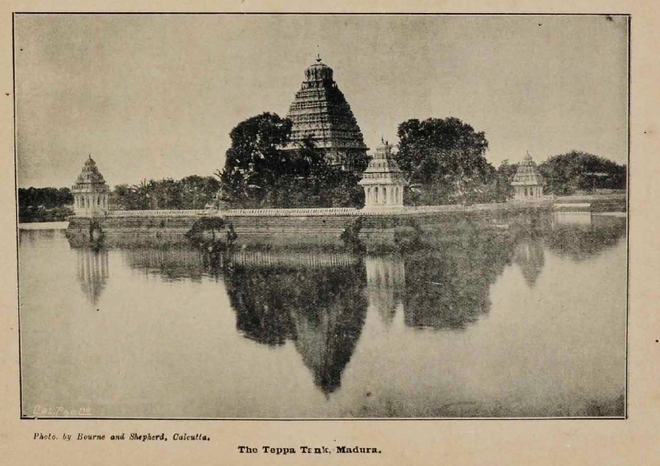

“Another celebrated building in Madura, now in great part ruined, is the Palace of Tirumala, one of the greatest of the rulers of the province, built by him in 1623. The hall is a quadrangle, two hundred and fifty by one hundred and fifty feet, and with an elaborate corridor, and one hundred and twenty-eight massive granite pillars ornamented with stucco, made from chuncim, or shell lime, which is a characteristic of the Madras Presidency. The British Government is now restoring it, and using it for legislative purposes.

On the other side of the town there is a lovely drive leading to a large sacred tank, the Teppu-kulam, with an island and temple in the centre. The road is arched over and shaded with banyan trees; and a very fine specimen of this tree is to be seen in the garden of the Collector”

— Indian Pictures; Rev. W. Urwick (1891)

swati.daftuar@thehindu.co.in