In a year of major sporting events – the Commonwealth Games, the FIFA World Cup, cricket’s T20 World Cup, the Winter Olympics – conversations on greening such events are more essential than ever. While the Brisbane Olympics are a decade away, lessons from events like these need to be applied from the start to maximise the benefits of the city’s transformation for the 2032 Games. Good planning can produce a positive environmental legacy for years to come.

In recent years, the focus on the impacts of such events on host cities, specifically the environmental impacts, has sharpened. As the costs of environmental degradation and climate change mount, Olympic plans must adapt to the host city’s sustainable development or redevelopment, as opposed to the city being developed around the Olympics.

Of course, these considerations are not new. Sustainability has been established as the third pillar of the Olympics since the 1990s.

Read more: Leaner, cost-effective, practical: how the 2032 Brisbane Games could save the Olympics

So what has been achieved so far?

Past Olympic hosts have tried to reduce their environmental impacts. Whether it’s planting trees to offset carbon emissions, cleaning up rivers, recycling materials to reduce waste, increasing public transport use, or using renewable energy, host cities have been making efforts and claims to be green for years.

And yet behind each host’s proclaimed success lies a multitude of shortcomings.

For example, host cities often need to improve or redevelop their transport systems. Most development projects in the past have been Games-specific rather than focused on improving the city for residents. The priorities are usually in areas most impacted by the event, so often don’t match residents’ ongoing needs.

We saw this in Rio de Janeiro, host of the 2016 Olympics. Projects were constructed in poorly planned locations with limited transport access. Only 15 of the original 27 venues hosted some sort of post-Olympics event. Others became deteriorating white elephants.

In London, multiple projects such as the Crossrail project were postponed before the 2012 Olympics. Residents’ needs were downgraded.

One must also wonder how the Olympics can be environmentally friendly when so many resources are diverted or newly invested in projects dedicated to an event lasting a couple of weeks at most.

Some Games, such as the 2008 Beijing Olympics, did improve aspects such as air quality that benefited all residents. However, these improvements were short-term, which is typical among host cities. Even for this year’s Beijing Winter Olympics, where organisers used renewable energy, retrofitted venues and considered a range of emissions, a more holistic approach would have improved outcomes.

Read more: Reduce, re-use, recycle: how the new relaxed Olympic rules make Brisbane’s 2032 bid affordable

What would a holistic approach look like?

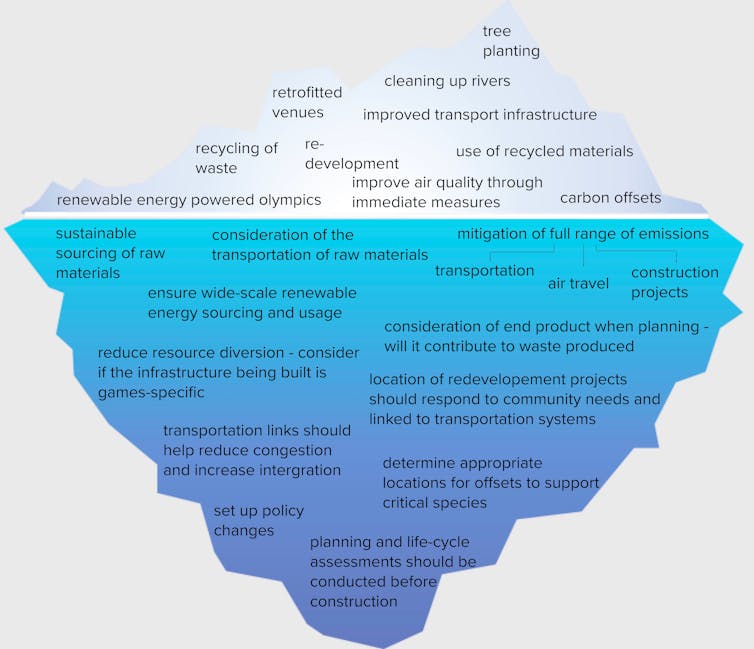

Host cities haven’t been approaching design, planning and hosting in the most comprehensive and sustainable way. They have tended to focus on the obvious tip-of-the-iceberg environmental impacts. However, many other issues are lurking beneath the surface, with interrelated knock-on effects.

For example, planting trees (as Beijing did) can help offset emissions and establish new habitat. However, it has been reported that the clearing of habitat in Songshan National Nature Reserve to house the National Alpine Ski Centre could affect vulnerable species. Planting trees as offsets does not excuse such irreversible impacts.

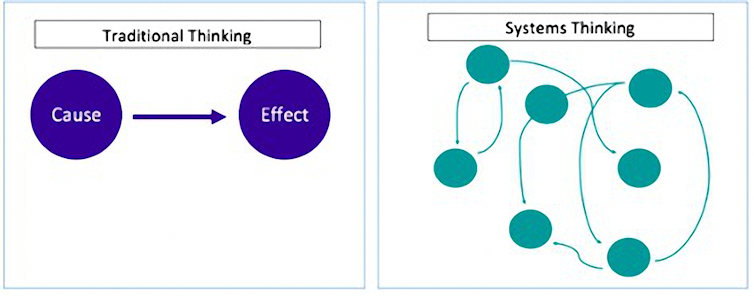

To host truly environment-friendly events, cities must consider the whole picture of emissions, resource consumption, waste production, transport links, habitat impacts and more. This requires a system-thinking approach that considers the life cycle of the product or project. It means planning where construction takes place, which venues can be retrofitted or recycled, what materials are used and where they are sourced. It also means deciding how construction projects will be powered and, ultimately, ensuring the resources invested in projects are not wasted after the event.

For the 2000 Olympics, Sydney set the standard by:

using materials with low environmental impacts and minimised waste

using solar power for venues and Olympic villages

conducting life-cycle assessments of environmental emissions and resource consumption

designing infrastructure to maximise energy-efficiency and more.

How can Brisbane do better?

So, how can Brisbane build on Sydney’s success? The detailed planning is still being resolved, but Brisbane’s more holistic approach gives the city a head-start. Its “climate-positive” commitment has four core principles:

repurposing and upgrading existing infrastructure

encouraging residents to change behaviours and be more environmentally conscious

implementing pollution and waste management incentives

better transport planning.

The master plan isn’t simply responding to selected environmental issues. Instead, Brisbane is on the path to a climate-positive Games through a combination of:

integrating public transport services

strategically locating venues across Queensland – 80% of the venues already exist

ensuring community needs across the state are met

investing in innovative solutions such as a sustainable hydrogen industry

promoting policy and behavioural changes to help solve deep-rooted issues.

However, Brisbane needs to go further by committing to life-cycle assessments of Olympic projects and following up on promised outcomes over the years.

Read more: The Brisbane Olympics are a leap into an unknowable future

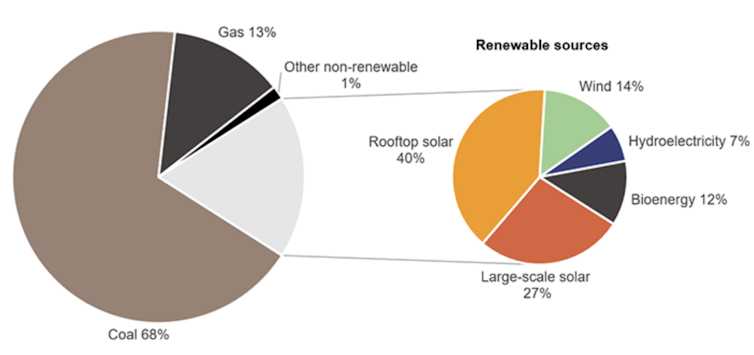

One shortcoming stands out in particular. Energy consumption and sourcing are not among the core principles for hosting the Olympics. Even if Brisbane were to achieve a zero-emissions event by using renewable energy, that doesn’t cover emissions from the next ten years of construction. And Queensland is still a mostly coal-powered state.

Brisbane is treating the Olympic Games as a platform for urban development that can transform how we travel, integrate multiple urban centres across South-East Queensland, and result in lasting changes to policies and behaviours. These goals stem from the importance of leaving a climate-positive legacy that will last.

This article would not have been possible without the research assistance of Manudi Periyapperuma and the funding support of UQ’s 2022 Global Change Youth Research Program.

Anthony Halog does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.