Anna Shackley begins recounting what she now remembers as “the worst day of my life”. It came in March last year, and played out in a hospital in Barcelona. Then still 22 years old, the Scot was undergoing a procedure to fix a cardiac arrhythmia, an irregular heartbeat, that had been detected two months prior.

“They call it an ablation,” she says of the procedure. “They go in through your artery in your leg, into the heart, and they burn the section that’s causing the extra beat.

“Everyone spoke really good English to me, but when they were doing everything, they were speaking Spanish. I couldn’t understand what they were saying, but I could tell they were getting more worried, because I was completely awake for it,” she says. “It was like three hours long. It was horrific.”

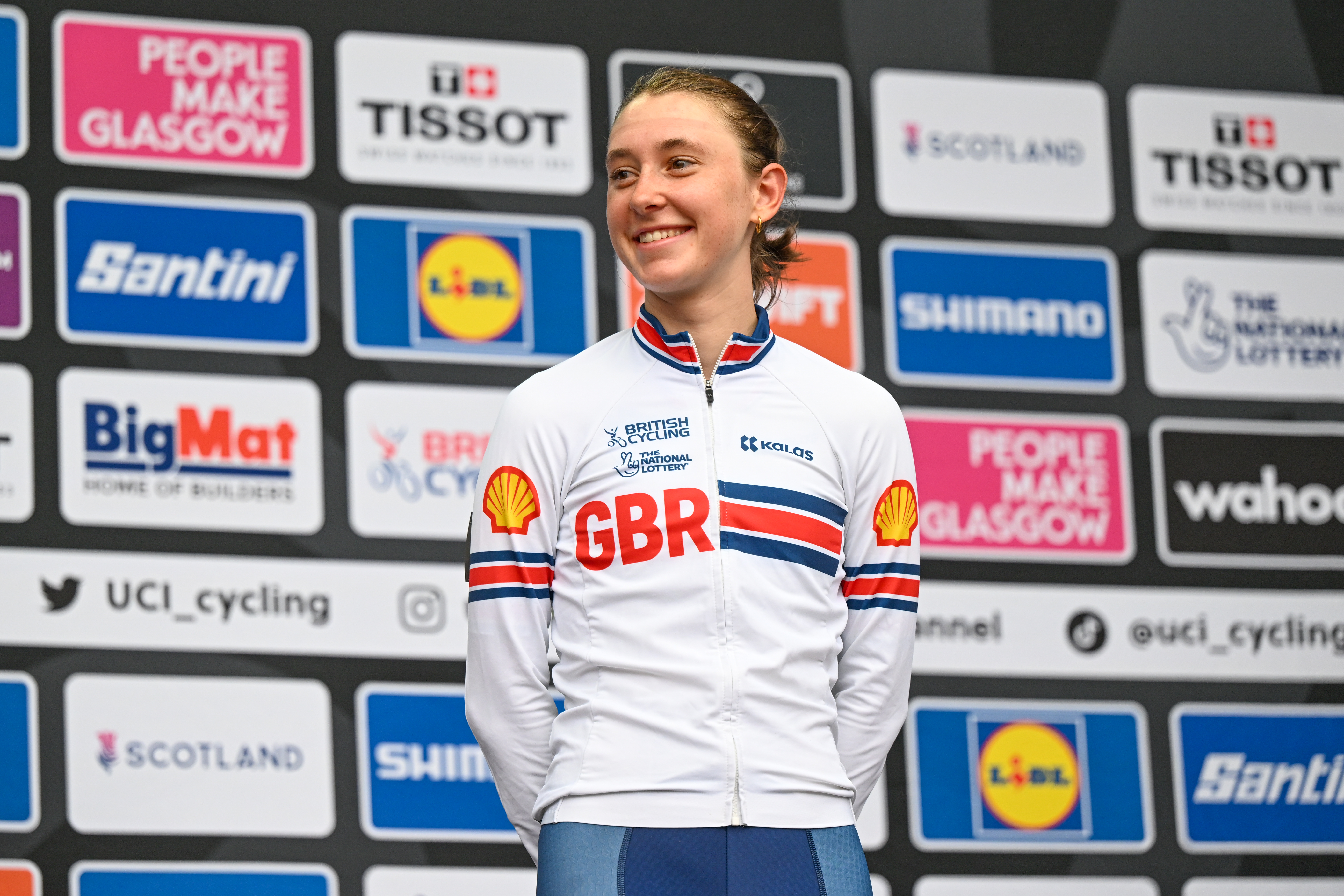

Then came the news. “They told me that it was a bigger problem,” the Scot says. The following month, the then SD Worx-Protime rider announced her early retirement from cycling. She had been a professional cyclist for three years, in which time she won an under-23 British national title, an under-23 bronze medal at the UCI World Championships, and became an Olympian.

“To say I’m devastated would be a huge understatement,” she wrote on Instagram at the time. It’s a feeling she still echoes today. “I’m happy with my career,” she tells Cycling Weekly, “but I feel like I could have given more in the future…” her voice trails off. “I feel I had so much more to give.”

Born in Milngavie, north of Glasgow, Shackley shone on the track and road as a child. She joined Scottish Cycling’s development pathway in her teenage years, and later British Cycling’s academy programme, graduating straight from the junior ranks to the WorldTour with SD Worx. The team, the best in the world, saw her as a promising climber, with future leader credentials. In December 2023, the clearcut path of her career veered sharply astray.

“Over the winter, I was having issues where I just felt like I couldn’t breathe on the bike, and I was having to stop,” she says. “Then I got Covid, and from then on, it got a lot worse. I’d have to stop and I felt my heart rate would just jump suddenly from like 120[bpm] to 180 and then back down again, having these massive spikes.”

At first, Shackley thought it was asthma, but her team medical in January revealed an irregularity with her heart. “They thought it was fixable,” she says. The ablation didn’t achieve what they’d hoped.

Even now, a year after her first diagnosis, the 23-year-old is unsure exactly what the issue is. “I still don’t have a proper name I can give it,” she says. “I just know it’s a ventricular arrhythmia, and it causes extra beats.” The doctors have told her it’s hereditary – “but no one in my family’s ever had any heart conditions”.

The extra beats, Shackley explains, come every day, and last for a few minutes at a time. “They’re only really bad if it’s sustained,” she adds, which is what happened at the end of June last year, when she had “an episode”.

“I had to get taken to the hospital and I had to get fitted with an emergency ICD [implantable cardioverter defribrillator]. I spent 10 days in the ICU,” she says.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m a bit of a hypochondriac, and having a heart problem, it made me feel obviously scared about what my life would be like in the future, and how long, basically, I’d live. But having the ICD has helped quite a lot, because I have that extra protection.”

Today, Shackley has gone from 25-hour training weeks to a mandate of no exercise at all. “I’ve just been doing walks,” she says. It took 11 months after her diagnosis before she got back on a bike, riding for half an hour leisurely with her boyfriend, careful not to exceed 100bpm. “I feel like that’s like a walk,” she says. “100’s very low.”

She also takes regular medication, which tires her muscles and makes her feel sleepy. “Sometimes I feel like I’m a cyclist without all the exercise,” the Scot laughs.

Through it all, the support she has received has filled her with gratitude. She cites Scottish Cycling in particular, who has helped her with NHS appointments, and set her up with a psychologist to guide her into retirement. “She’s been a great help for me,” Shackley says.

“It’s just been really nice to talk to someone about it. Now, I feel like I can watch my friends race and be happy for them that they’re doing really well, without being really sad that I’m not there too.

“I’ve been trying to look into maybe getting an e-bike, because I really enjoy the social aspect of riding,” she continues. “It’d be nice to get back to that.”

Shackley has big plans for the next chapter of her professional career, too. Between her hospital visits in the spring last year, she sent a message to Bob Lyons, manager of Scottish Continental squad Alba Development Road Team, and joined the team as a sports director at the Tour of Britain Women. “I felt quite useful,” she says proudly.

“When I stopped, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, but I felt like I wanted to stay in cycling. I feel like I’ve had quite a few years of all this knowledge built up, and I wanted to use it, not just be a waste.”

In October, Shackley travelled to Aigle in Switzerland to complete the UCI’s official sports director course. “I’m quite young to be a DS, I realise,” the 23-year-old says. And yet, she’s finalising a contract to work part-time for a Continental team in 2025, with a view to one day rejoining the WorldTour. Things, finally, are looking up. A sense of optimism seizes her voice.

“I feel excited to go into the year and have a job and have a routine and just have more of a normal life,” she says.

There’s also an extra motivation to succeed. During a low point last year, the Scot’s former SD Worx-Protime team-mate Christine Majerus sent her some Lego, to help take her mind off her heart condition. “It’s really therapeutic. I love it,” Shackley says. “You can switch your mind off and clip all the pieces together.” But, she adds: “It’s an expensive hobby to get into.

“I just need to get a job that pays me enough to buy some more Lego.”