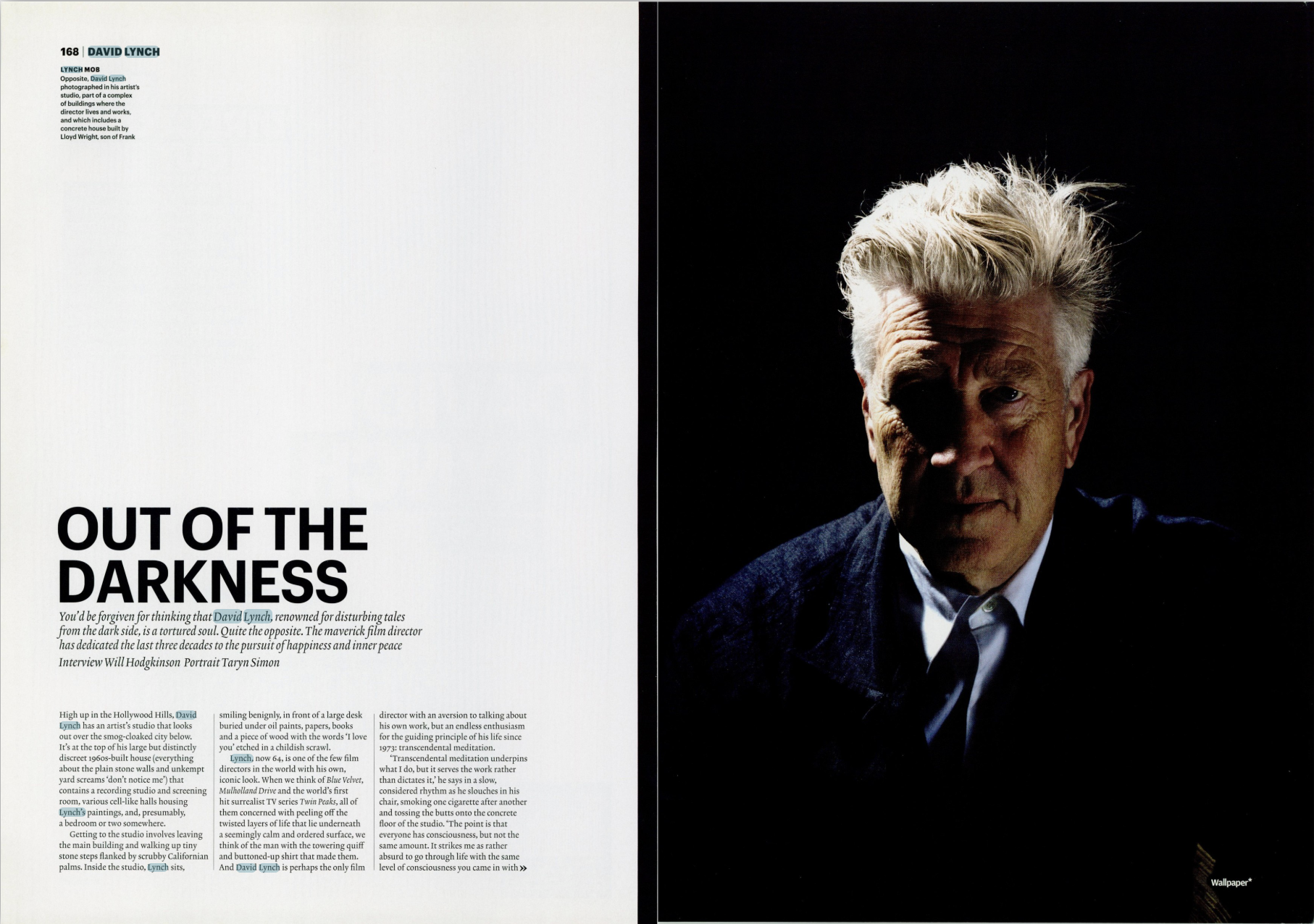

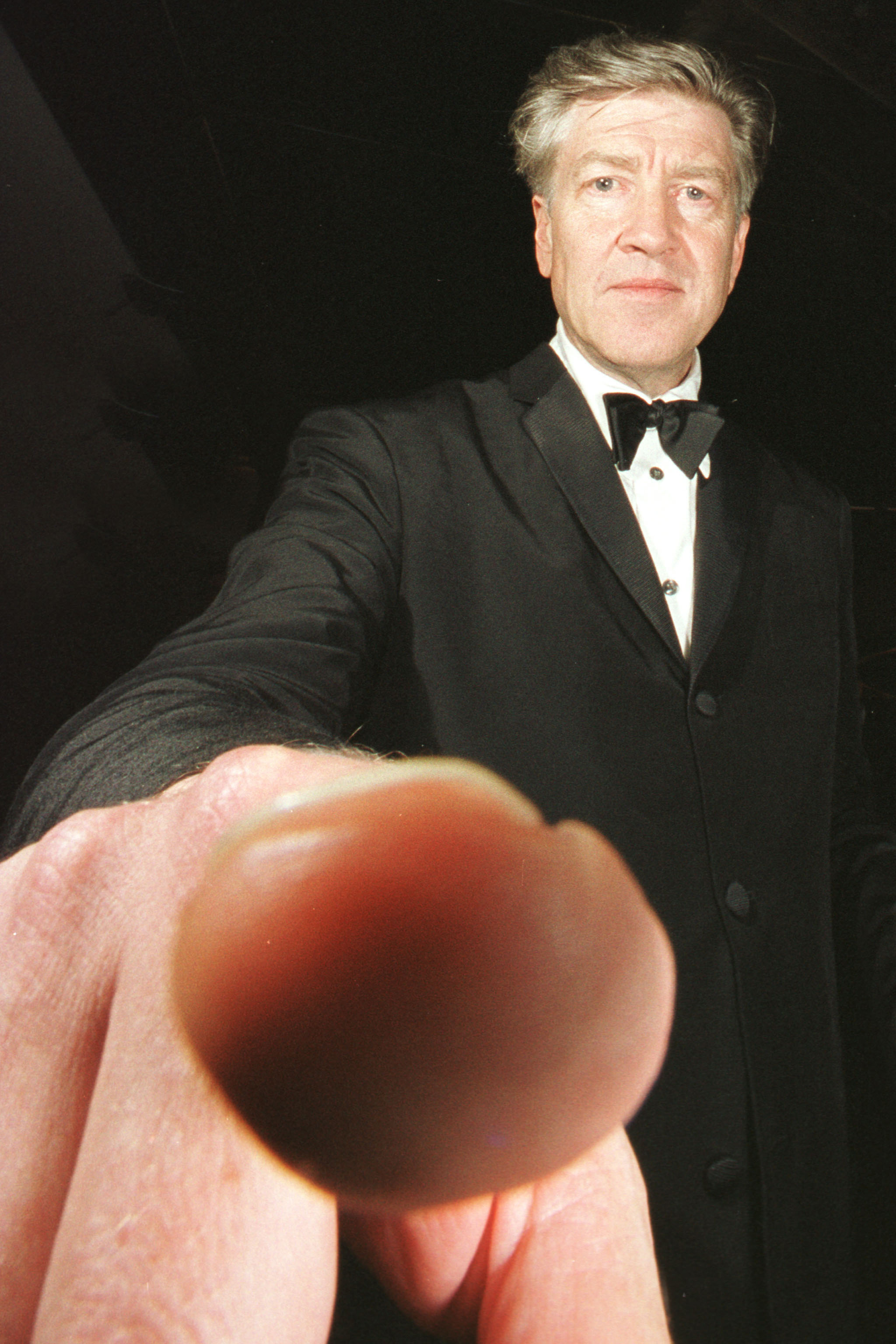

As the world mourns David Lynch, who died on 16 January 2025, aged 78, we look back on the time he joined us as Guest Editor of Wallpaper*. The following interview was first published in the October 2010 issue of Wallpaper* magazine.

You'd be forgiven for thinking that David Lynch, renowned for disturbing tales from the dark side, is a tortured soul. Quite the opposite. The maverick film director has dedicated the last three decades to to the pursuit of happiness and inner peace.

High up in the Hollywood Hills, David Lynch has an artist's studio that looks out over the smog-cloaked city below. It's at the tip of his large but distinctly discreet 1960s-built house (everything about the plain stone walls and unkempt yard screams ‘don't notice me’) that contains a recording studio and screening room, various cell-like halls housing Lynch's paintings and, presumably, a bedroom or two somewhere.

Getting to the studio involves leaving the main building and walking up tiny stone steps flanked by scrubby Californian palms. Inside the studio, Lynch sits, smiling benignly, in front of a large desk buried under oil paints, papers, books and a piece of wood with the words 'I love you' etched in a childish scrawl.

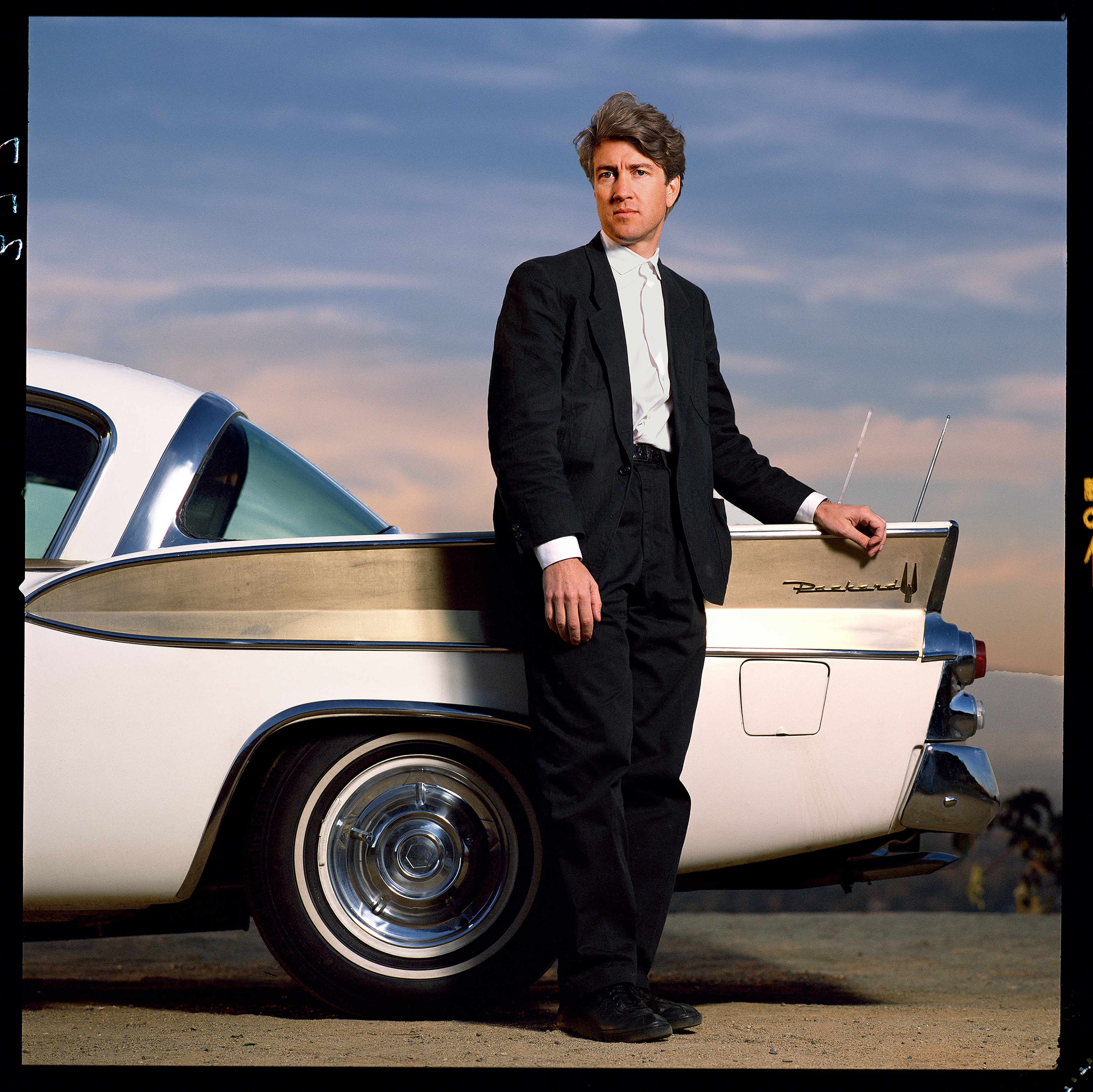

Lynch, now 64, is one of the few film directors in the world with his own, iconic look. When we think of Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and the world's first hit surrealist TV series Twin Peaks, all of them concerned with peeling off the twisted layers of life that lie underneath a seemingly calm and ordered surface, we think of the man with the towering quiff and buttoned-up shirt that made them.

And David Lynch is perhaps the only film director with an aversion to talking about his own work, but an endless enthusiasm for the guiding principle of his life since 1973: transcendental meditation.

'Transcendental meditation underpins what I do, but it serves the work rather than dictates it,' he says in a slow, considered rhythm as he slouches in his chair, smoking one cigarette after another and tossing the butts onto the concrete floor of the studio. 'The point is that everyone has consciousness but not the same amount. It strikes me as rather absurd to go through life with the same level of consciousness you came in with when there is a technique to expand it, and that technique is easy, effortless and supremely profound.'

The technique, of course, is the ancient mantra-based system brought over to the West by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1957 and which subsequently attracted such high-profile adherents as the Beatles, Mia Farrow, Jerry Seinfeld, Sheryl Crow and Def Jam founder Russell Simmons.

'It takes you to the field of unity, first time, every time,' Lynch claims of transcendental meditation. 'And when a human being really and truly experiences that...' he makes the sound and gesture of a muted explosion.

This is where Lynch's guest spot at Wallpaper* comes in. Initially sceptical at the proposition of adding magazine editor to a CV that includes film director, painter, musician, worldwide lecturer on transcendental meditation and coffee salesman (he's got his own eponymous brand), Lynch came round to the idea of using the magazine as a canvas for a series of painting that underpin what he considered to be the great goal of all human life: unity. In the past, Lynch has acknowledged the influence of such psychologically multi-layered artists as Francis Bacon, Jackson Pollock and Edward Hopper. For this project, he is aiming to project images of absolute simplicity and spiritual purity.

'I can't talk about these symbols of unity because the symbols speak for themselves', states Lynch, a phrase to chill the heart of any interviewer, before, thankfully, adding: 'These are ancient things, from many cultures, and they're beautiful to look at because the field of unity is at the base of all matter and mind. It's an eternal field, always the same, always full. Unity is the home of total knowledge and all the laws of nature.'

To put this metaphysical statement into manifest form, Lynch summons up from his computer a scientific equation for unity. It's extremely complex. I can't begin to pretend to understand it , and I'm not entirely sure Lynch does either, but in essence it gives a mathematical explanation to the higher state of consciousness that Lynch is on a mission to share with the world.

'The whole purpose of understanding unity is to expand happiness, which is not a bad thing,' he says. 'Transcendental meditation will get you to that field of unity, that state of infinite consciousness. Consciousness is tied in with intelligence, creativity, happiness, love, energy, power, peace... all positive things. That's why I want to talk about them.'

It might come as a surprise that the man associated with exposing the dark recesses of the psyche has dedicated his life to the search for spiritual peace.

Lynch, who has meditated twice a day, every day, for over three decades, sees no contradiction between making noir masterpieces like Blue Velvet – which starts with the discovery of a severed ear in a field and gets increasingly sinister from then on – and spreading the Maharishi's message of love.

'I make things that are troublesome,' explains Lynch. 'That's because my ideas come from our world, and our world has negativity and absurdities. I love absurdities. I fall in love with ideas for two reasons: firstly for the idea itself and secondly for what cinema could do to it. In the old days I had plenty of ideas, but there was hollowness in the happiness department and many worries. Negativity restricts the flow of creativity, and suffering is not the friend of creativity.'

But isn't suffering the very bedrock of artistic inspiration? 'Baloney,' booms Lynch, sounding like James Stewart in the midst of regression therapy. 'That myth started, I think, in France. I love the French, but the starving artist in the garret image is absurd. It's romantic to be hungry and poor if you're a man because that means chicks will want to look after you. But if you're starving, dirt poor and shivering, you're not going to enjoy any kind of work, even if you are able to do it. Suffering doesn't bring ideas. If it did, we could just hit someone with a mallet and an idea would pop out. People on chain gangs would be the greatest artists in the world. "Please let me go on that chain gang!" budding artists would cry.'

Lynch's assistant, who has possibly been briefed to come in and terminate the interview, pops her head around the door. But he's in full flow, so he sends her off to make some more coffee, albeit in a polite, calm way. Further talk of the importance of finding happiness through inner peace rather than material accumulation leads Lynch to explaining how great ideas come to him in the first place.

'Films start with a fragment, a piece of the puzzle,' he explains. 'The puzzle exists in the other room. I get hold of one piece, and I love it so much that it attracts other pieces to come in and join it. And pretty soon the puzzle is in my room. I certainly don't know what the film is about until further down the line.'

He cites the example of his 1976 breakthrough feature Eraserhead, an impressionistic portrait of a shy young man trapped in a nightmarish industrial town as he faces up to the birth of his bizarrely deformed, screaming child.

'I didn't know what Eraserhead was about. Then I was reading the Bible and I came upon a sentence and my head was blown off.' Whatever that sentence was, Lynch isn't saying. 'The point is that these things come later. A lot of people say: "I want to do a film about a certain thing." For me, it's not that way.'

Even if the idea comes from a piece of writing already out there, Lynch sees the process as the same. 'Books and scripts are ideas in organised form,' he says. 'There isn't a difference between an original idea and getting excited by a book or a script because it involves the same process of falling in love with the thing. Wild at Heart was a novel by Barry Gifford, and when you read a great book it comes alive in your head, just like catching an original idea. You see it all, and then you just have to turn it into a film.'

Lynch's last film was the supernatural mystery thriller Inland Empire, released in 2006. Since then he has presented a series of short, touchingly direct profiles on everyday Americans called Interview Project, which share the innocence and guileless charm of The Straight Story, Lynch's 1999 road movie about an elderly man riding a lawnmower from Iowa to Wisconsin to mend his relationship with his sick, estranged brother. He has also been painting, working with wood, and giving lectures on transcendental meditation. Given the evangelical zeal Lynch has for transcendental meditation – he's never more animated than when describing the remarkable calming effects it has had on violent prisoners and children diagnosed with ADD – it's tempting to believe that this has taken precedence over moviemaking. Lynch refutes this.

'I love to work,' he says emphatically. 'I like to stay at home. I don't like to talk in public and I don't like to travel. When I was asked to do a tour of 13 universities and talk about transcendental meditation, I thought: well, that's the end of my career. Nobody will want to hear this. And sure enough, not everybody did. But people are like detectives: they sense whether things are true or false pretty fast and for so many people this sounded true. It felt good to get that message out there.'

It's almost time for Wallpaper* to take a taxi back down the hill, to the world of concrete and frantic optimism that is West Hollywood. We know this because Lynch's assistant has arrived in the studio with a banana on a plate, which appears to be some sort of termination symbol. But there's still time for Lynch to throw in a surprise admission.

'I love plumbing,' he announces. Can he fix toilets? 'I've cleaned toilets. I can fix hot water heaters. I like pipes, pipe fitting, cutting threads ... all those things. I used to do it to make money.'

If the filmmaking, painting, lecturing on transcendental meditation, reflecting on the development of consciousness, and guest-editing dry up, it's good to know that David Lynch has a skill to fall back on. Before we say goodbye, he reiterates the one message he wants to get across in his stint as editor more than anything else: that happiness can only come from within, from finding unity.

'There's a line from the Vedas [sacred Hindu scriptures] that says something to the effect of, man has control of action alone, never the fruits of the action. If you understand that, then when your film comes out or your painting goes up on a wall, bad reviews won't hit you so hard and good reviews won't turn you into an egomaniac. Dive within; unfold higher states of consciousness until you reach supreme enlightenment. Then things that used to kill you won't kill you anymore. That can only be a good thing.'

One Love

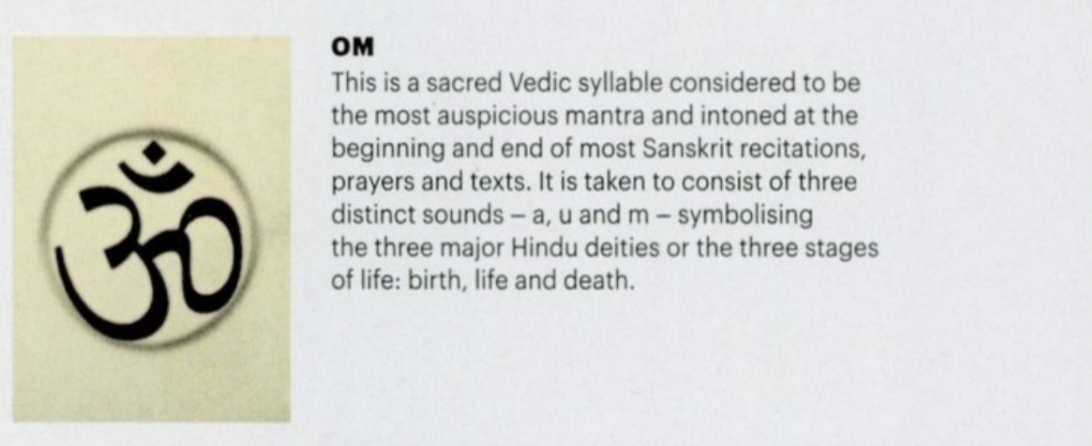

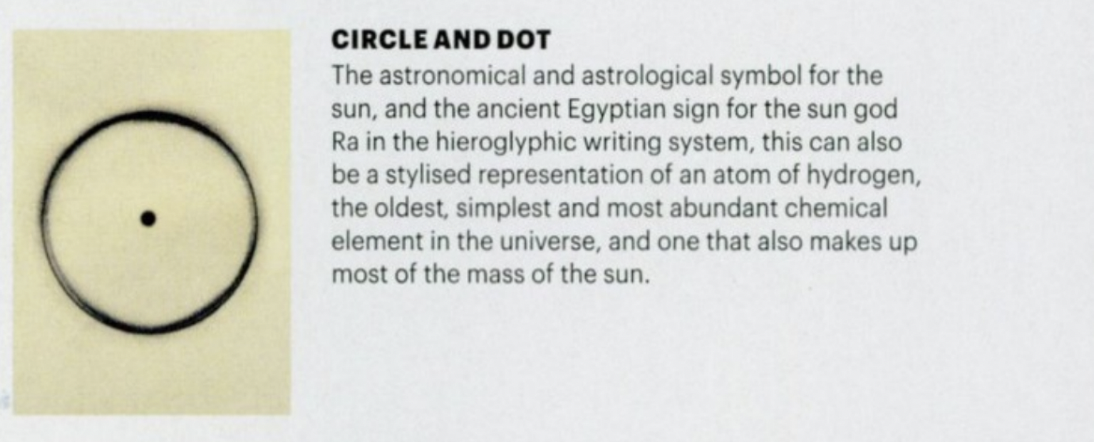

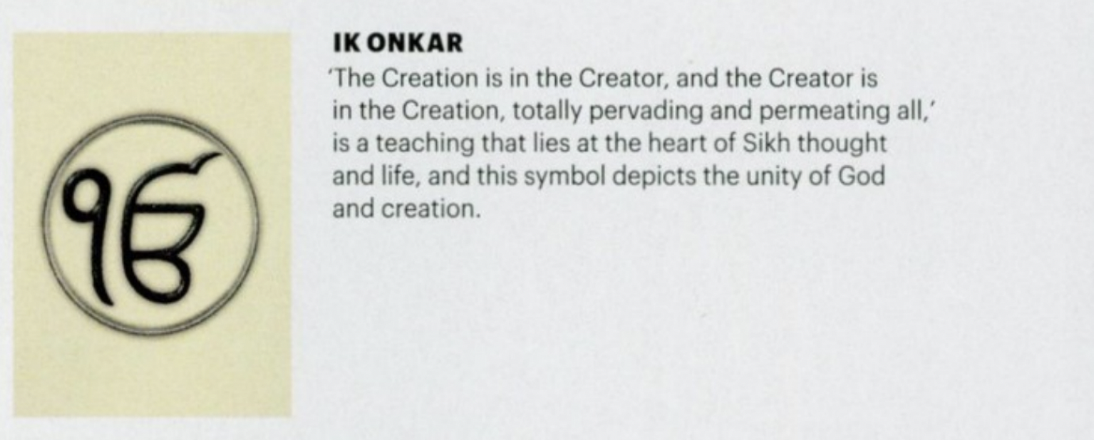

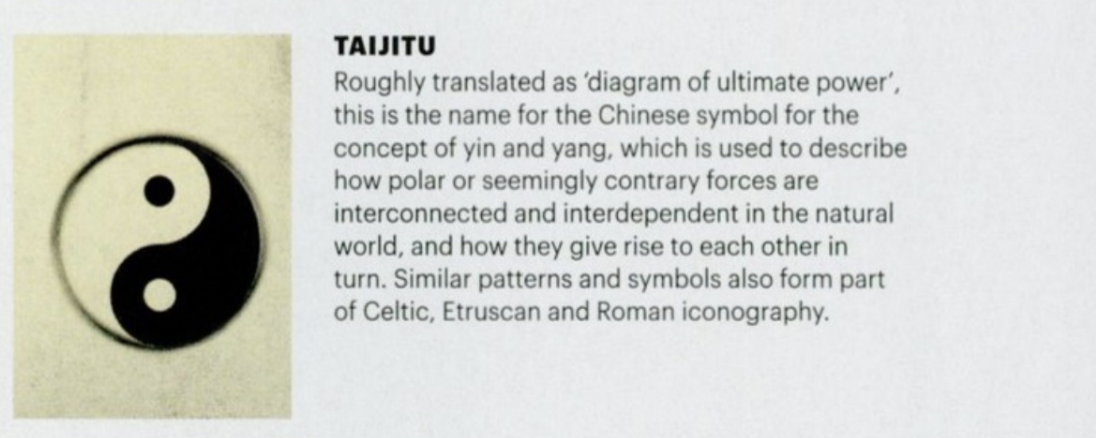

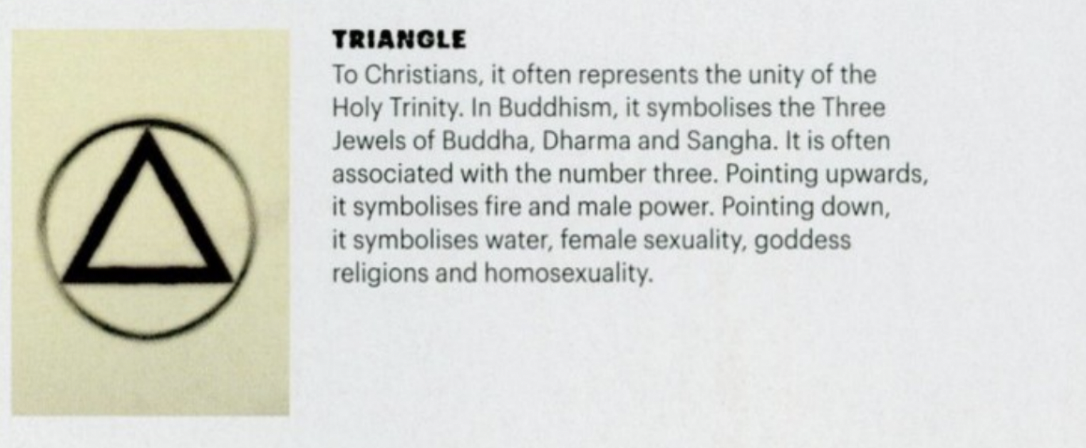

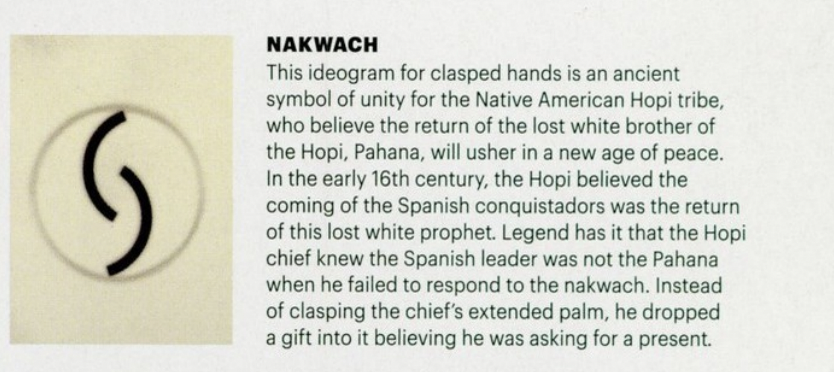

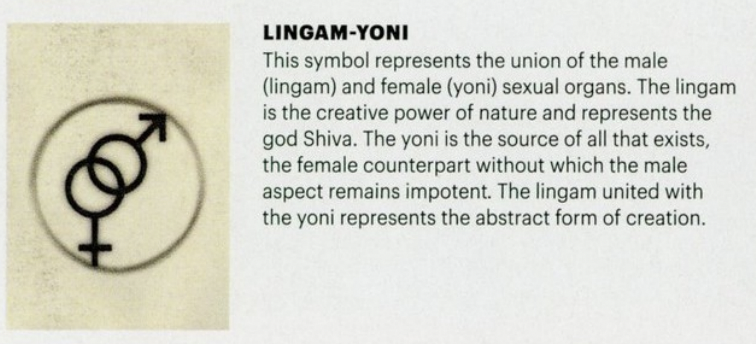

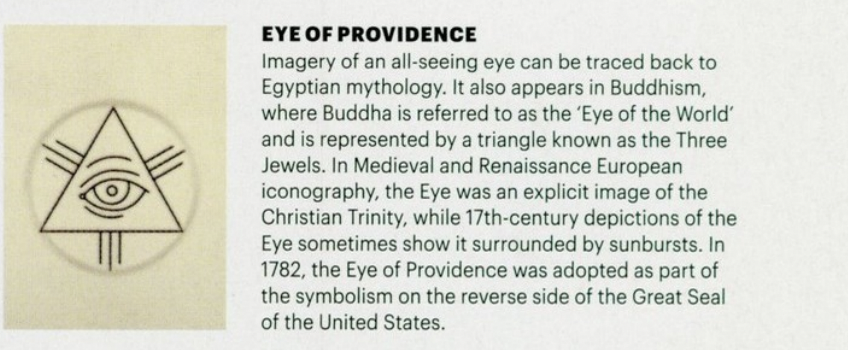

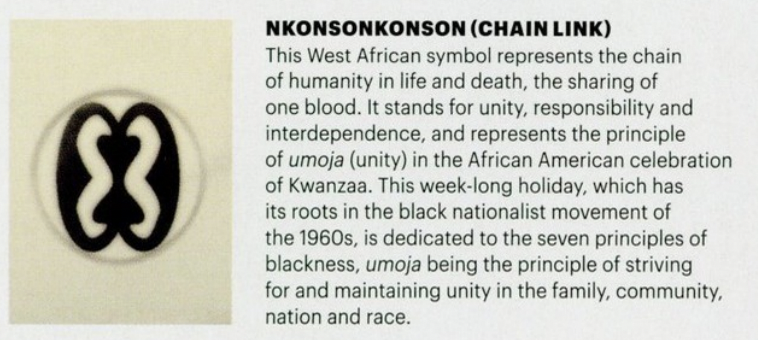

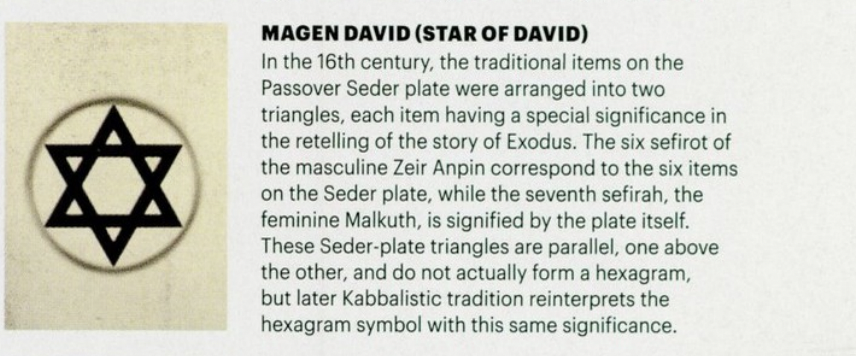

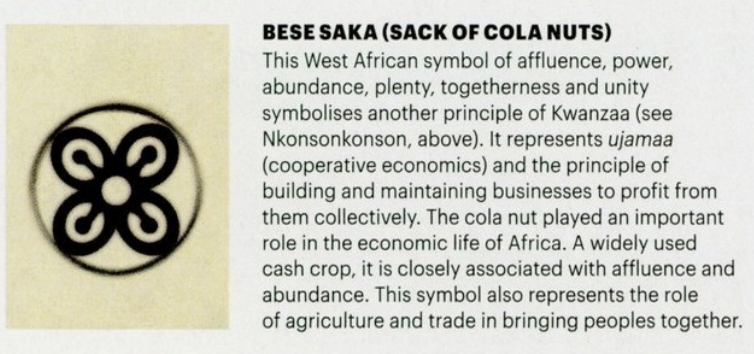

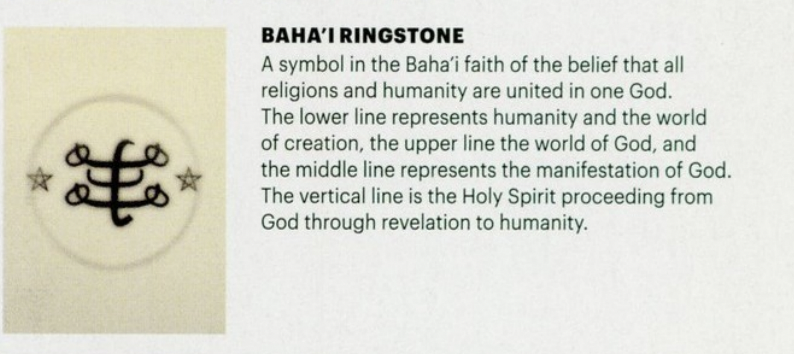

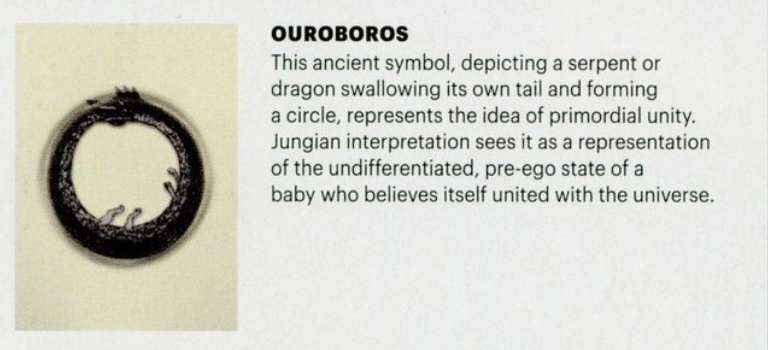

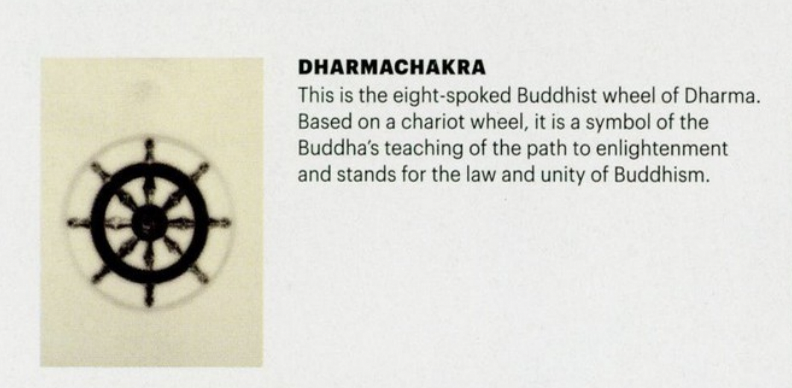

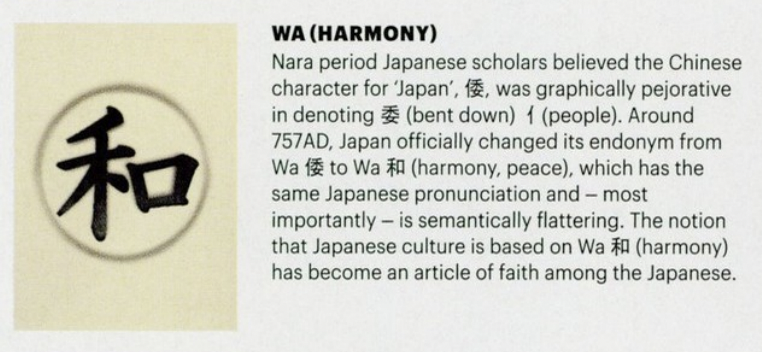

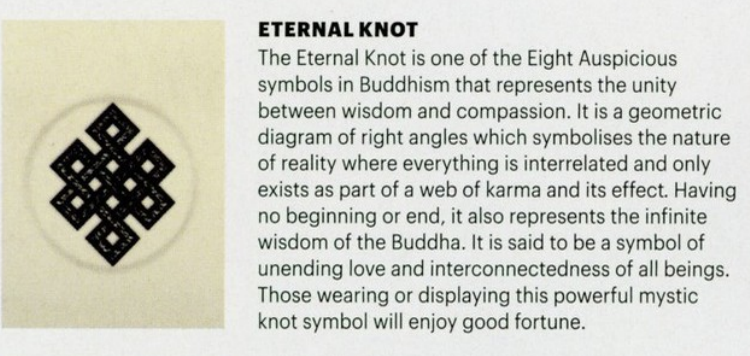

As guest editor, David Lynch chose to illustrate a number of symbols that represent unity in various religions and cultures – presented here. Lynch uses a great deal of symbolism in his movies, but much of it is often lost on the average viewer, so, after an afternoon with our ancient texts, we attempt to explain what it all means.

Words: Paul Mccann