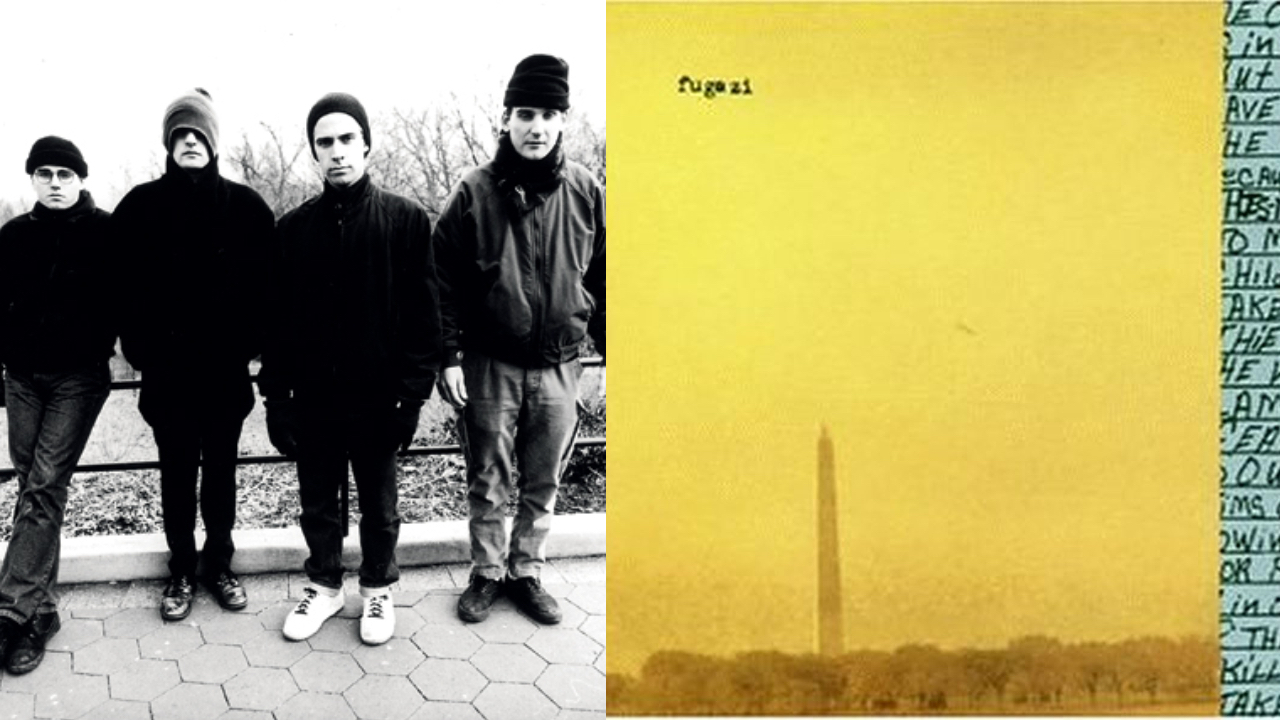

On September 24 and 25, 1993, Washington DC's Fugazi played sold-out shows at New York's 3,200-capacity Roseland Ballroom on their US tour supporting In On The Killtaker, their third full-length studio album, released three months previously. While the very idea of hosting celebratory after-show parties would have been hilarious to the quartet, vocalist/guitarist Ian MacKaye, co-vocalist/guitarist Guy Picciotto, bassist Joe Lally and drummer Brendan Canty did welcome one famous music industry legend to their dressing room in NYC, Atlantic Records co-founder Ahmet Ertegun, the man who signed Led Zeppelin, Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Rolling Stones and more.

This was not purely a social call: the record industry mogul was there to make America's greatest punk band an offer they could not refuse, or more accurately, an offer he sincerely hoped they would not refuse. Ertegun was aware that In On The Killtaker had given Fugazi their first entry on the Billboard 200 chart, and with the might of Atlantic's money and muscle behind them, he enthused, there could be no limit to what they could achieve.

“Last time I did this was when I offered The Rolling Stones their own record label and $10 million,” he told the four musicians.

Fugazi listened politely, but didn't ever entertain the offer.

“It would have been the most stupid and self-destructive thing we could possibly have done,” Guy Picciotto reflected in 2011, sitting across the table from me in Dischord House, home of the independent record label Ian MacKaye co-founded in 1980, which released every record Fugazi made. “It'd be basically like saying, 'Do you want to jump off a cliff?' It wouldn't have made sense to us.”

“He was a nice man, and we talked to him about DC [where Ertegun grew up],” Picciotto said with a smile, “but there was nothing he could offer us.”

Though they never flexed their status, within the independent record world, Fugazi were a big deal long before 'The Year That Punk Broke', the title of a Sonic Youth/Nirvana European tour documentary which became a media soundbite in the wake of Nirvana's worldwide 'breakthrough' with their 1991 album Nevermind. The DC group's debut full-length album, 1990's Repeater, sold 200,000 in its first 12 months on the racks, and speaking to me at Dischord House, Ian MacKaye recalled “a guy from Geffen was driving me nuts in 1991, just calling and calling and calling me.”

“I knew Fugazi were selling records, but I was too busy to spend much time thinking about it,” he admitted. “We never had a manger, we never toured in a bus, we never rode in a limousine, so really things always seemed kinda the same for us, regardless of how many records were being sold. At some point it became clear that there were bands who were selling a quarter of what we sold, and they were a huge deal, with journalists and managers around them, but partly because we ignored the game, and didn’t talk to people, we were left alone.”

As much as Fugazi chose to ignore the game, to quote MacKaye, the noise around Nirvana's major label debut in late '91 was such that it was all but impossible not to be aware of their dizzying ascent from the underground music scene to the mainstream. In Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad's truly essential document of the American indie underground community, Guy Picciotto told the writer that while touring Australia at the time, “It was like our record [1991's Steady Diet Of Nothing] could have been a hobo pissing in the forest for all the impact it had. Nevermind was so huge, and people were so fucking blown away. We were just like, What the fuck is going on here? It was so crazy. On one hand, the shows were bigger, but on the other hand, it felt like we were playing ukelele's all of a sudden, because of the disparity of the impact of what they did.”

"I kinda regret that quote," Picciotto told me 20 years on. "We had released a record simultaneously with them, and there was this sudden Nevermind phenomenon, but the reason I regret that comment is that it suggests that we hadn't achieved anything up to that point. 1991 was an arbitrary mid-point on a very long journey that had been going on and it got built up and marketed in a way that makes sense in sales terms, but to me, culturally, it just doesn't seem particularly significant.

Before Nirvana there was no sense that there was a bag of gold sitting around somewhere

Guy Picciotto

"I'm not denigrating the bands that exploded then or the records that were made - a lot of incredible things happened at that time - but there was a fuck of a lot going on before and since... It's not like we were the Dodo that was still wandering the earth, there were plenty of other bands working the same way we did, plenty of other people helping us maintain what we were doing, it was a true network. It wasn't like we were the last standard bearers. It was a scene. But it became strange and it distorted the discussion with bands.

"Nirvana were an anomaly, the scale of what they were able to do was profound. But the way it coloured bands' perceptions of what was going on out there was pretty destructive, ultimately... a lot of people got fucked up by it. There's always going to be an underground, there's always going to be bands playing on the margins and people finding ways for that to happen, but what changed was the discussion and what people focussed on. Before there was no sense that there was a bag of gold sitting around somewhere, there was other shit to talk about.”

Talking in a Georgetown coffee house that same week, Ian MacKaye offered his own insightful comparison on the time.

“So, okay, we’re having a conversation here, and there have been a couple of moments where they turn on the machines and we get drowned out,” he said. “And to some degree that’s 1991 to me. At times we got drowned out by the machine, but that doesn’t mean we weren’t talking and we’re not communicating, we just got drowned out at times.”

By way of an example of how things changed, MacKaye spoke about how dozens of rock band promo videos shown on MTV from summer 1991 onwards featured stage-diving and crowd-surfing, which led to more injuries at gigs, which led to increased security, and necessitated additional safety precautions being put in place... with bands expected to absorb the additional costs.

“We played one show to 4000 people one night and the barricade made more money than we did: the barricade cost more than we made,” he said with a wry laugh. “And that’s not even factoring in the 30 security staff you have to hire to man that barricade. It was just psychotic, and it had nothing to do with music: it wasn’t a physical response to music, it was like a behavioural hypnosis caused by television. Dealing with everyone else’s success was a headache for us, a real nightmare: it fucked with our thing and just gave us more work to do.“

In November 1992 [note: Ian MacKaye suggests it may have been a year earlier, though Fugazi were on tour in Australia, New Zealand and Japan in November '91, whereas they played a total of just 3 shows, two of them in DC, in the final five months of '92], in a break with their traditional working practises, Fugazi travelled to Chicago to record for the first time with an old friend. Before finding infamy with Big Black, and before acquiring a reputation as one of the world's most knowledgeable recording engineers, as a fanzine writer Steve Albini had written a brutally scathing review of the self-titled debut album by Rites Of Spring, Guy Picciotto and Brendan Canty's 'Revolution Summer' emo-core band, but a mutual respect and deep friendship had developed between the musicians across the intervening years.

“At some point I remember Steve saying, 'Hey, if you guys ever want to record something, it's on me,“ Ian MacKaye recalled in 2015 during a two-part episode of the Kreative Kontrol podcast, on which Albini was also guesting. “So we always had that in our back pocket as a possibility, which was really nice... In '91, or '92, we'd been working on these songs, but we just kinda hit a wall at some point... and I suggested to the band, like, Hey, why don't we just get out of town, let's go to Chicago for a weekend, and record two songs with Steve... I rented a minivan, and Brendan had a Volvo station wagon, so we just threw our gear in the back of the two vehicles, and Joe and I drove up in the minivan, and Brendan and Guy drove up in the Volvo, and we went right to Steve's house. We loaded in on a Friday, and I said, We're just going to do two songs, and three days later we had recorded, like, 13 songs, and it was the greatest session we ever had, we had a blast. Hanging with Steve, and working in the studio, was such a pleasure, and so enjoyable, and so fucking fucking funny... we just laughed and laughed. The session was just incredible, we had such a great time.

On the night-time drive back to DC, MacKaye recalls, he and Lally popped their cassette copy of the session into the mini-van's stereo and were surprised and bemused to hear that it sounded, in their view, “it didn't sound right.“

Back at home, the band members discussed the recording, and all four men agreed that it sounded “kinda weird.“

“And then two days later, or a day later, I got a fax from Steve, and he said, 'I think maybe we kinda fumbled on this one.' But I don't know what it was.“

On the same podcast, Albini admitted that the recording wasn't his “finest hour“ as an engineer.

“It's the luck of the draw,“ he mused, philosophically. “It's just as likely that we could have done the session and had it come out awesome, but, as it turns out, it came out in a way where we enjoyed everything about except the results.“

The versions of Public Witness Program and Great Cop recorded by Albini are nothing short of incredible

On the Kreative Kontrol podcast, MacKaye was quick to add a final thought.

“I have to say, I can remember sitting in the attic where the mixing room was, and listening to it - we were doing a playback - and I remember thinking, This is the greatest record ever made. I was so ecstatic, thinking, like, Take that Sonic Youth! [Laughs] Or whoever was a big band at the time. I was thinking, This is going to be incredible!

“But it was a very important experience for Fugazi... mostly I think we just needed to take more time recording: if we'd spent a week there it probably would have been a different thing.“

For those less invested in the process, however - that's everyone but the five men involved - there is much to recommend about the shelved session, or at least those songs which have leaked online over the years: in particular, the versions of Public Witness Program and Great Cop recorded by Albini are nothing short of incredible. But if nothing else, the weekend helped solidify some of the previously unfinished arrangements, and helped untangle some of the knottier sections which had frustrated the band in DC prior to their trip to the Mid-West.

Ultimately, the final, band-approved version of In On The Killtaker was recorded in the more familiar setting of Inner Ear Studios, by Ted Nicely, who had previously worked with the band and studio owner Don Zientara on Repeater.

Written in the wake of the 1991 Gulf War, and containing references both oblique and overt to national discord, nationalism, US history, scene politics, and the value and virtue of retaining voices uncorrupted by commerce, it's a dense, disquieting listen, which bears scant resemblance to anything else being marketed as 'alternative rock' in the early '90s. At its most aggressive, Great Cop retains the fury captured in Chicago - Ian MacKaye calling out those questioning his band's intentions and motivations with the brilliantly cutting, back-handed compliment "You'd make a great cop" - and Smallpox Champion finds Guy Picciotto referencing America's shameful, murderous treatment of Native Americans with allusions to contemporaneous military action abroad, noting "history rears up to spit in your face" and warning "You'll get yours".

Opener Facet Squared simultaneously critiques nationalism ("flags are such ugly things") and Gen X apathy ("Cool's eternal, but it's always dated"), the latter attitude also referenced on the album's most accessible track, Public Witness Program, with Picciotto spitting "I like to walk around it, I'm paid to stand around". Elsewhere, on closing tracks Instrument and Last Chance For A Slow Dance there are more oblique reflections on loss and imperfect, fractured human relationships, while Cassavetes, a salute to independent film-maker John Cassavetes, celebrates heartfelt outsider art made without interference or compromise, with lyrics - "If it's not for sale you can't buy it" - which can be read as both a caution to peers signing up to major labels and a clear and unambiguous 'No, thanks' to those seeking to buy into Fugazi's world. Ahmet Ertegun must have skipped over that one...

If one were to look at chart stats and sales info without any knowledge of context, In On The Killtaker could be seen as Fugazi's most 'successful' album, charting at number 24 in the UK, and number 153 in the US. But, speaking to me in 2011, Ian MacKaye cautioned against such an interpretation, with typically dry humour.

“One could argue that with the high tide all the boats rise: In On The Killtaker was a very popular record, and I imagine that was largely the result of the tidal interest,“ he noted. "But I imagine there’s more unlistened to copies of …Killtaker than any other Fugazi album, people sitting at home thinking, ‘Why did I buy this?’ We were just trying to steer, just trying to manage our own world.“