Sarah Clegg’s Woman’s Lore: 4,000 Years of Sirens, Serpents and Succubi is about ancient demonic figures, expressly the infamous child-killing monsters of the Near East and Mediterranean. Intimately tied to childbirth and infant and child mortality, such monsters were female in form.

Often, they were negatively connected to female sexuality. Chronicled over centuries, monsters such as the Mesopotamian Lamashtu, the Greek Lamia, and the Hebrew (and Mesopotamian) Lilith are, in Clegg’s thesis, a significant part of women’s lore, “a tradition kept alive by women, that tells the story of women’s lives, from 2000 BC to the present day”.

Review: Woman’s Lore: 4,000 Years of Sirens, Serpents and Succubi – Sarah Clegg (Bloomsbury)

Clegg begins with Lamashtu. Born of divine parents but quickly disowned because of her inherently evil nature, Lamashtu was the subject of curses written on clay tablets designed to drive her away from vulnerable mothers and children.

Included in the spells are some spectacularly graphic descriptions of her, such as the excerpt below, which comes from one of the oldest extant incantations (c. 1800 BCE):

She has hardly any palms but very long fingers

And very long claws.

The spell describes her as having the face of a dog, and as slithering along “like a snake”. This physiognomy made Lamashtu perfectly designed to wreak havoc on her intended victims; her long fingers and claws were used to tear at babies’ stomachs to generate infection and to reach into mothers’ wombs and cause premature birth and miscarriage.

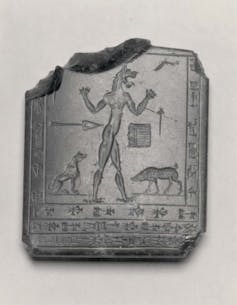

Belief in this figure of abjection and fear extended beyond Mesopotamia and there was a robust trade in amulets made of diverse materials, reflecting a belief in Lamashtu across different socio-economic groups.

Lamashtu’s body was subject to change, depending on the source. Clegg includes an amulet, from 800–500 BCE, which depicts her with the head of a lion (a traditionally male symbol in Mesopotamian culture), clutching snakes and suckling animals.

She has bird talons for feet and stands atop a donkey (this donkey, it was hoped, would carry Lamashtu to the Netherworld and away from her victims).

Her embodiment as the antithesis of the archetypal mother is evident in her suckling animals, a dog and a pig, in a parody of the maternal figure who nurtures human babies.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Enheduanna, princess, priestess and the world's first known author

Beauties and demons

The ancient Greeks and Romans had their own equivalent to Lamashtu: Lamia, “a direct descendent of the Mesopotamian child-and mother-killing demon” (Clegg notes the etymological connection between the names Lamashtu and Lamia).

Lamia was also a seducer of young men – a skill she managed by concealing her monstrously snaky lower body parts. She also ate babies and children and, like other Mediterranean monsters, such as Mormo and Empousa, was a shapeshifter.

Mythologies surrounding the origins of Lamia are redolent with themes of female loss and pain. In one version of how Lamia came into being, Durius of Samos, writing in the third century BCE, explains:

Lamia was a beautiful woman in Libya. Zeus had sex with her. Because of Hera’s envy towards her she destroyed the children she bore. Consequently she became misshapen through grief, snatched other people’s children and killed them.

While other accounts have Lamia as a fearsome and destructive monster from the start, Durius’ story highlights the vulnerability of women as subject to rape and subsequent punishment. Such plot lines are common in Greek and Roman myths, pointing to the casualisation of rape in certain socio-political circumstances.

Clegg’s first two chapters on these creatures examine women’s lore through the monstrous feminine. And, along the way, her book provides a host of related cultural history on magic, ritual, and ghost traditions, offering a series of poignant insights into women’s lives in these ancient societies. An excerpt from an incantation against Lamashtu composed for a woman to recite, reads:

I was pregnant, but unable to bring my child to term; I gave birth but did not bring a child to life. May a woman who can grant success release me […] may I have a straightforward pregnancy […]

Herein is the pain of a woman who did not carry her baby to term, the grief of still birth, and the desperation to bear a healthy child.

Such insights into women’s lived experiences are also evident in the category of demons called the Lilitus, whom, Mespotamians believed were “the spirits of young girls who had died still virgins, before marriage and before children”.

Robbed of a future, the Lilitus were forever seeking to fulfil sexual initiation or male contact, driving them to visit sleeping men. These visits were the Mesopotamian aetiology for wet dreams and night discharge. Clegg regards Lilitus as more to be pitied than hated, citing an incantation:

She [a Lilitu] is a woman who has never seen a city feast, nor ever raises her eyes, who never rejoiced with the other girls, who was snatched away from her spouse, who had no spouse, nor bore a son.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Ovid's Metamorphoses and reading rape

Feisty Lilith

Clegg’s book is divided into nine chapters, each covering a specific culture and demon or selection of demons (with some, such as Lilith, the first wife of Adam in Jewish folklore, occupying several chapters). There is also a useful timeline for readers without detailed knowledge of the chronology and a fascinating epilogue on contemporary remnants of these beliefs.

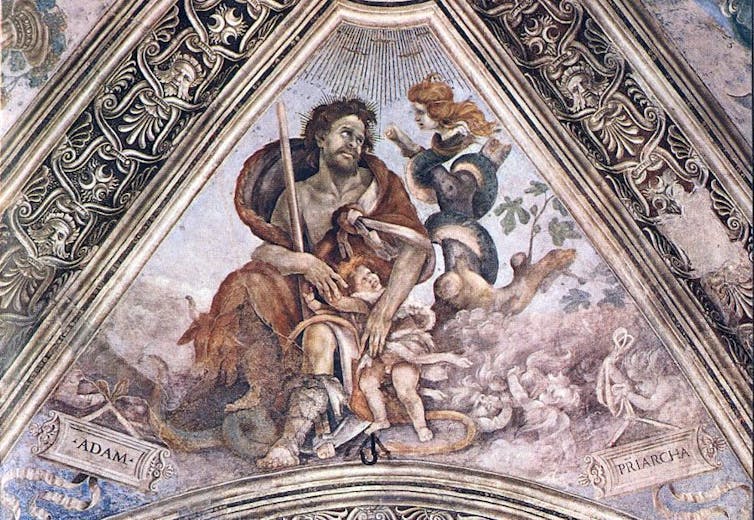

Judaic Lilith, like her sister-demons, has an aetiology that helps us understand her, albeit with a sense of fear or anxiety. As Clegg discusses, Lilith – as a prototypical feminist of sorts – flees the Garden of Eden when her husband denies her equality (in short: he refuses to let her “on top” during sex).

She wreaks her revenge by hanging outside the walls of Eden, attacking pregnant women and children, and – no surprise – seducing men.

This manifestation of Lilith, its first extant documentation appearing in the Alphabet of Ben Sira (c. ninth or 10th century CE), intricately associates her with Eve as a kind of oppositional paradigm. While the feisty Lilith refuses to submit to patriarchy, a submissive Eve accepts the order of things.

In the Kabbalistic tradition as it developed in the early modern era (c. 13th century) as illustrated in The Treatise on the Left Emanation, Lilith is permitted to justify her protest:

I cannot return because of what is said in the Torah – ‘Her former husband who sent her away, may not take her again to be his wife, after that she is defiled,’ that is, when he was not the last to sleep with her. And the Great Demon has already slept with me.

Herein, Lilith is given a voice and tells us that she did not, in fact, flee but was sent away by Adam. Additionally, once banished, a woman can never return. But, then again, who can trust the words of a demon?

Enduring spells

Clegg also discusses the ancient Greek demon, Gello who is, like the Lilitus, “a jealous ghost who murdered children and young women”. Traditionally associated with old wives’ tales – nursery stories to frighten and thereby control naughty children – Gello was the ghost of a young virgin who had died before fulfilling her social role of wife and mother. As a cultural signifier, Clegg explains:

Gello, then, was a prematurely dead girl causing the premature deaths of other girls; a hideous, warped form of reproduction, whereby instead of having the children she so wanted, Gello turned other hopeful young girls into thwarted, jealous monsters like herself.

By the Byzantine era, however, scepticism grew as to the existence of such beings. Church law, writes Clegg, insisted that these monsters were “a deception of the devil, and not to be believed”. Nevertheless, Clegg notes, these traditions continued, often among women, who continued to believe in the effectiveness of magic for protection against such forces.

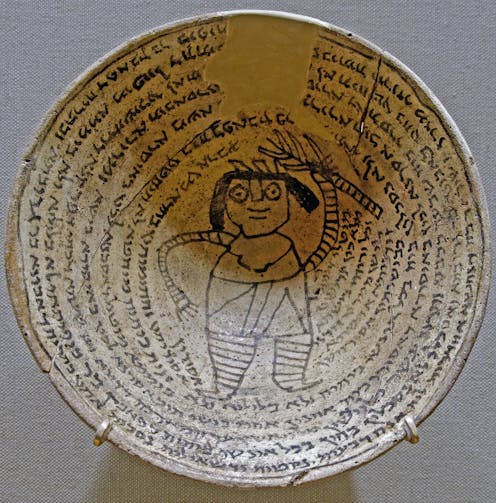

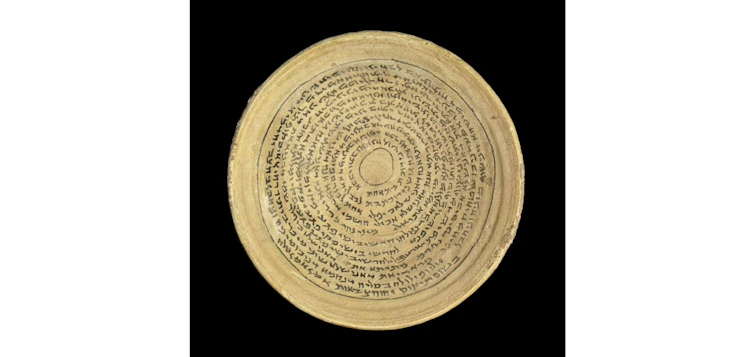

Like the curse tablets designed to drive away Lamashtu and the amulets made to protect individuals from her, there were also demon (or incantation) bowls, used in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria from the sixth to the eighth centuries CE. These earthenware bowls were inscribed with spells (mostly in Jewish-Aramaic) and magical images, such as crudely drawn pictures of the target of the spell, including Lilith.

They were designed to entice and then trap evil forces, and thus rid the bowl’s owner of danger, especially disease.

While magic was largely practised by men throughout the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean, Clegg includes several examples of women inscribing their own demon bowls.

For example, there is a cache of bowls written by the same woman, Giyonay (otherwise unknown). Giyonay writes one bowl spell to drive Lilith away from her husband and herself and others to protect members of her family.

Melusine and contemporary incarnations

Clegg also examines mermaids, particularly in Medieval traditions, tracking their connections to earlier demons, such as the Lamia who, as Clegg notes, were believed to swim the waters of the Greek islands until the 1980s.

We also meet Melusine, a beautiful, serpentine female from Europe (particularly France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries). Clegg suggests that she is also a successor to Mediterranean and Eastern demons, including Byzantine fantasies of Gello possessing a snake-tail. She is, however, more akin to the fairy or fae creatures of Europe and Britain (which Clegg does concede).

Melusine’s backstory reads like a classic fairy tale, complete with feminine deception and a narrative taboo. Told by Jean d’Arras in Roman de Mélusine (The Story of Melusine) in the 14th century, it chronicles Melusine’s marriage to the mortal, Raymond. Like most marriages between mortals and non-mortals, Melusine and Raymond’s union ends in tears. While the couple are initially happy, their marital bliss ends when Raymond breaks the one taboo that Melusine insists on: not to enter her chambers on a Saturday.

The act, which reveals Melusine in her true form as she enjoys a bath, sets in chain a series of disasters, culminating in Raymond cursing her – at which point she transforms into a dragon and flies away forever.

While Melusine may be a monster, Clegg points out the positive aspects of her, including the cultural capital she brings to the mortal family tied to her.

A child or a descendent of these fairy marriages was viewed as something to be proud of: a sign of greatness much like being a child or descendent of a god in ancient Greece or Rome.

Additionally, Melusine builds, albeit by magic, some pretty impressive infrastructure for her husband, including – or so the story goes – the very real, Château de Lusignan.

Clegg’s final chapters deal with later receptions of these terrifying, seductive, bewitching, destructive and ultimately intriguing female monsters.

In chapter nine the reader meets some of these creatures in contemporary guises. Herein, Lilith dominates. We meet her as a symbol of second wave feminism through to the latest manifestations of the same and also an icon of modern spiritual worship. We read of the origins of the Australian feminist research journal, Lilith, and the appropriation of the demon by Octavia E. Butler in her Lilith’s Brood trilogy.

Clegg also includes a revisioning of the tricksy Melusine, transformed in Serge Ecker’s 2013 statue, erected in Luxembourg for the city’s 1050th anniversary.

As Clegg rightly observes, these ancient figures:

have proven enormously adaptable to women’s causes – symbolizing everything from the need to leave home and husband to find equality to sexual freedom and LGBTQ rights.

Marguerite Johnson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.