The French Broad River winds through the mountains of western North Carolina, fed by dozens of mountain streams, and crosses the city of Asheville. At over 2,000 feet above sea level and more than 250 miles from the coast, it is an unlikely place to prepare for a hurricane.

Yet, the remnants of several hurricanes have swept through this region over the years, sending rivers in the region raging out of their banks.

When these storms hit back to back, the devastation can be enormous. In September 2004, for example, remnants of Hurricanes Frances, Ivan and Jeanne all brought excessive rain to western North Carolina in the span of a few weeks, overwhelming the French Broad and other rivers in the Asheville area.

Western North Carolina’s history is just one example of the inland risks from tropical cyclones.

In 1955, Connie, followed closely by Diane, produced some of the worst inland river flooding in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts. Diane became known as the first billion-dollar storm. The compound impacts prompted Congress to fund major studies of hurricane meteorology and protection efforts.

Vermont was caught off guard by Tropical Storm Irene in 2001, which swept away hundreds of homes. In 1998, Tropical Storm Charley traveled nearly 200 miles up the Rio Grande Valley, quickly flooding the dry Texas landscape, with devastating consequences. The remnants of Hurricane Ida in 2022 caused nearly US$84 billion in damage as its heavy rains caused flooding in states from Louisiana to New York.

I am a historical geographer who researches flood hazards and how communities both exacerbate the risk and respond. With the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 to Nov. 30, expected to be exceptionally busy, storms like these are a reminder to mountain communities and other inland regions across the U.S. to prepare.

Tough lessons from North Carolina’s mountains

Western North Carolina provides an important case study of a hurricane season risk that might seem rare but can be catastrophic. It also shows how some communities are starting to respond.

In July 1916, the Asheville area was deluged by back-to-back tropical storms that tore apart river bridges and roads, washed away businesses and left large parts of the city under water.

The first tropical storm made landfall in Mississippi and meandered into the Southern Appalachians. As it lingered over western North Carolina, 6 to 10 inches of rain fell in the mountains, running off into creeks and then into rivers, including the French Broad.

A week later, a second tropical storm moved ashore, this time in South Carolina and headed for the already saturated ground of the French Broad River basin. It dropped 12 to 15 inches near Brevard. Weather Bureau forecasters wrote that saturated soils allowed 80% to 90% of the new precipitation to run off the mountains into French Broad River tributaries.

At Asheville, the river rose to 23.1 feet – a record more than 5 feet higher than any crest before or since. The water washed out bridges and damaged most businesses and industries on the floodplain.

Dozens of people died in the flooding, and commerce was disrupted for weeks. The Santee River, which flows seaward from the Blue Ridge Mountains, destroyed some 700,000 acres of crops in South Carolina.

Responses to the 1916 storms weren’t enough

After the storms, there was talk of replacing some devastated structures with flood-proof buildings. However, the importance of rail transport and the limited amount of land for commercial and industrial uses compelled reconstruction near the river. Congress approved a flood control study in 1930, but no structural protections were built. Revised building codes and land use restrictions to reduce flood impacts came much later.

Then, in September 2004, the region was hit with back-to-back tropical storm disasters again.

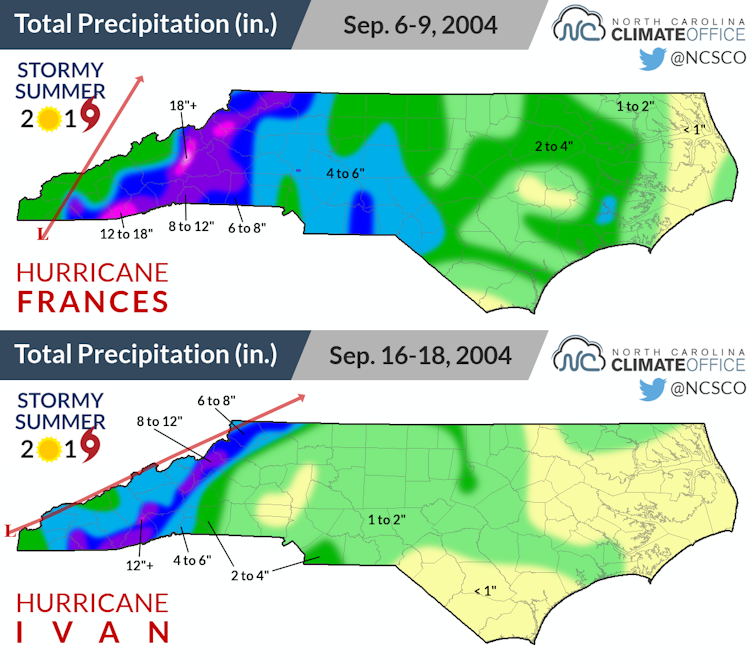

Hurricane Frances made landfall on Florida and eventually climbed the Blue Ridge Mountains into Western North Carolina. Remnants of the hurricane dumped 8 to 12 inches of rain near Asheville. Black Mountain received 14.6 inches, which flowed into a French Broad River tributary, triggering widespread flooding where the rivers meet. The torrent severed a water main and cut off drinking water to Asheville residents.

Shortly after Frances hit, Hurricane Ivan roared ashore in Alabama and moved inland, bringing 4 to 12 more inches of rain to the French Broad basin over three days. Saturated soils on the mountain slopes lost their grip and caused numerous landslides, and portions of Asheville and Brevard flooded. Remnants of Hurricane Jeanne brought even more rain to western North Carolina a few days later.

Using the past to plan for the future isn’t enough

Traditionally, officials planning for hazards like hurricanes have relied on records of past events to guide their decisions. However, this approach assumes that the climate is stable, and that just isn’t the case.

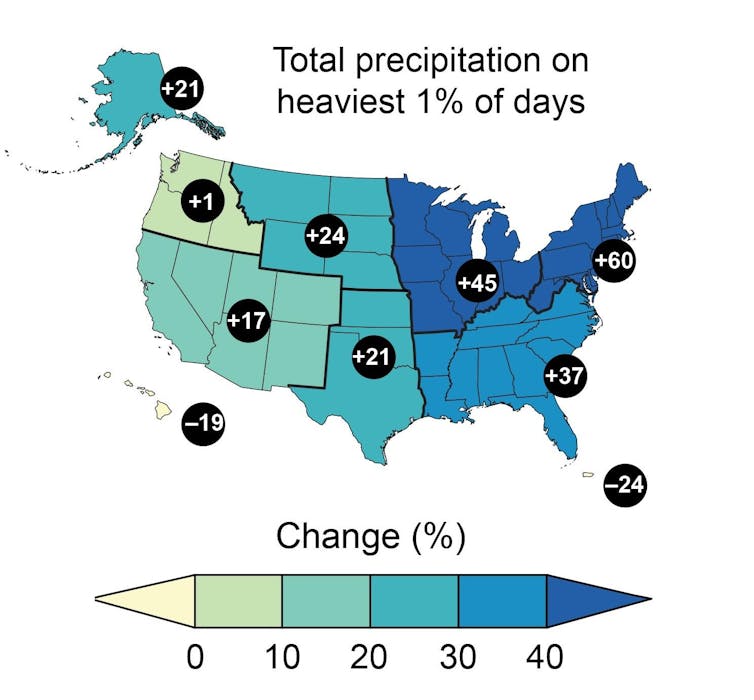

As the climate warms, the air can hold more moisture, meaning tropical cyclones – as well as inland thunderstorms – can deliver more rain.

This can be particularly troublesome as giant storms move inland and cause streams and rivers to flood. Back-to-back storms can be even more destructive. New development in areas that were once unlikely to flood may be more susceptible as the climate heats up.

Some communities are starting to consider how future risk might worsen.

In the Asheville area, Buncombe County’s hazard mitigation plan now explicitly recognizes hurricane risks and acknowledges that “future occurrences are likely.”

Following the 2004 flood, the county modified its use of a water supply reservoir to include storage of floodwaters, and it now requires new buildings constructed in areas inundated in 2004 to be elevated 2 feet above the base flood elevation. The city of Brevard, 30 miles south of Asheville, restricted construction in flood-prone areas to limit future losses.

Asheville has created green spaces along the French Broad River and has made efforts to enlarge stormwater retention behind dams on tributaries. But altering stormwater drainage systems is costly when the existing systems were designed to meet historical rainfall levels, rather than the scale of rainfall that will accompany climate change.

Extreme weather events, including mountain and inland flooding, are becoming a frequent problem across the U.S., and I believe they demand greater consideration in disaster planning at all levels. For communities, preparing for these future risks requires learning from past floods but also recognizing that future storms may produce flooding that goes beyond the scale of anything seen before.

Craig E. Colten received funding from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. No direct funding supported this particular study.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.