Before seemingly every Chinese smartphone brand was chasing “flagship killer” status with high-end handsets at shockingly low prices, Xiaomi was there first.

In the span of just a few years after its founding in 2010, Xiaomi became China’s top smartphone maker and one of the country’s most valuable start-ups, aided in part by its hunger-marketing tactics of selling limited batches of phones.

But by 2016, the company’s lustre started to fade as it focused on lifestyle products that included smart devices like wearables and not-so-smart products like luggage and umbrellas.

It was then overtaken in handsets by its larger competitor Huawei Technologies Co and rival upstarts like Oppo and Vivo, both owned by the Dongguan-based conglomerate BBK Electronics.

Now Xiaomi is back on top, and the company has lofty ambitions, with its first electric car in the pipeline. Here is a look at the rise and fall and rise of Xiaomi.

How did Xiaomi get started?

Xiaomi was founded in Beijing in 2010 by a cohort of six people, led by 51-year-old entrepreneur Lei Jun, who remains the company’s CEO.

The smartphone maker’s early growth came from cultivating a dedicated fan base and engaging with users online. Rapid iteration made Xiaomi popular in the Android community.

The start-up could move so fast because its first product was actually software – the MIUI ROM designed to work on specific handsets from other brands, allowing users with the know-how to replace their phone maker’s software. Xiaomi smartphones still run on MIUI today.

Even though smartphone ROMs catered to a niche community, it generated excitement on forums like XDA-Developers, where people gushed over iPhone-like aesthetics arriving on Android. By paying attention to online forums and listening to its users, Xiaomi was able to quickly roll out new features in high demand.

Having built up a support base of enthusiastic fans, Xiaomi released its first smartphone, the Mi 1, the following year, receiving 300,000 pre-orders for the phone in the first 34 hours.

It is no surprise given the specifications: it was running Qualcomm’s flagship processor at the time, the Snapdragon S3 – the same one in Samsung Electronics’ Galaxy S II. But at a price of just 1,999 yuan (US$300), it cost less than half of what its competitor was charging.

Low prices and regular engagement with users made Xiaomi devices widely coveted. Xiaomi users were also very dedicated to their phones. By one estimate from Flurry, Xiaomi users spent more time using apps on their phones on average in January 2014 than iPhone users.

Xiaomi also came up with a clever trick to control supply shortages and keep costs down. By selling only online, initial batches of phones were sold through so-called flash sales, or sales of a limited number of units at designated times. This tactic would eventually lead to initial stock selling out within seconds.

The tight control on stock kept Xiaomi from guessing about demand for new handsets, ensuring they were only making what they could sell. Xiaomi would also keep devices around for as long as two years, making the margins on each handset greater over time as component costs came down.

The strategy was so successful that other Chinese smartphone makers replicated it. Overseas consumers loathed the flash sale model, however, making it difficult for a company like OnePlus, which primarily targeted overseas buyers and eventually gave up the model.

Flash sales also became less important for Xiaomi as the company grew. Eventually, it found other avenues for driving sales: physical retail and smart home products.

Does Xiaomi only sell online?

In September 2015, Xiaomi opened its first bricks-and-mortar location in Beijing, and it had a familiar aesthetic: products neatly spaced out along wooden tables. But walking into any competitor’s store today – whether Microsoft or Huawei – will evoke similar Apple vibes.

Xiaomi pioneered China’s budget smartphone e-commerce model, but eventually growth would demand expanding beyond cyberspace for sales.

As other brands would also find out, giving consumers a place to try products is a good sales strategy. Rapid expansion of physical retail in lower-tier cities is one method that allowed competitors Oppo and Vivo to overtake Xiaomi for a time in 2016.

As Xiaomi expanded globally, its retail locations have also multiplied. It has been particularly successful in India, where it set a Guinness World Record for most stores opened simultaneously with 500 new shops in November 2018.

As of last year, Xiaomi had more than 1,800 stores in China and 6,000 locations worldwide.

Why does a smartphone company sell so many other things?

“Xiaomi was never meant to be just a smartphone vendor,” Lei said at the 2016 Summer Davos event in Tianjin, state-run newspaper China Daily reported at the time. “Instead, we are aiming to offer consumers a wide range of products at affordable prices.”

Xiaomi has since gone on to tout the power of its ecosystem as a driver of growth as it expanded in the internet of things (IoT) with myriad connected devices, from simple wall outlets to appliances like air purifiers and rice cookers.

In 2016, Lei said the company needed 40 different kinds of electronic products to keep consumers shopping in their store. He also noted that the company had already invested in 55 different smart hardware manufacturers.

Xiaomi now offers a lot more than just 40 different products, but they are not all electronic, nor are they all smart.

Despite billing itself as an IoT company, Xiaomi has pursued a model more akin to Japanese lifestyle retailer Muji. Some of the company’s best-selling products are “dumb” items like backpacks, luggage and umbrellas. For a time, it was almost impossible to leave home in a Chinese city without seeing people everywhere carrying Xiaomi’s iconic, boxy business backpack.

The company’s smart home ambitions are real, though. Like Samsung and Apple, Xiaomi has its own Mijia (or Mi Home) ecosystem that ties together diverse devices like TVs, projectors, smart speakers, routers and refrigerators.

Xiaomi has also used investments in other brands to bolster its offerings. Huami, the maker of the Amazfit wearables line now known as Zepp Health in English, makes Xiaomi wearables like the widely popular Mi Band, once the best-selling wearable in the world.

Xiaomi is also the principal investor in Beijing-based Ninebot, the electric scooter company notable for buying – and later shutting down – Segway in 2015 following a patent dispute.

By having so many product offerings, Xiaomi became a competitive e-commerce platform. Lei said in 2013 that it was China’s third-largest e-commerce platform, something that does not hold true today amid fierce competition in China’s e-commerce sector.

Xiaomi sells through multiple platforms now, and it remains a popular brand for many products.

Is Xiaomi just an Apple copycat?

In its early years, Xiaomi gained a reputation for shamelessly copying Apple design aesthetics. Lei even invited comparisons to Apple co-founder Steve Jobs with his Apple-like product presentations, where he typically wore a black shirt and blue jeans.

This aspect of Xiaomi remains part of the company’s DNA, as was made clear with the Mi Watch released at the end of 2019. The company’s laptops will also look familiar to MacBook users, but as with its stores, Xiaomi is far from the only hardware maker borrowing from Apple in that department.

However, Xiaomi has become more than a company delivering Apple-like devices for less money. As the company has grown in clout and revenue, it has started investing more heavily in research and development, coming up with designs and technologies that cannot be seen anywhere else.

The most obvious example of this is the company’s concept phone line Mi Mix, which is meant to show off experimental designs and features. The line has largely been focused on turning out giant phones that are almost all screen.

Xiaomi has also teased speculative technology like Air Charge, a box that can purportedly charge devices from several meters away. Other companies have been working on similar technologies, but there is no sign of commercial viability yet.

How did Xiaomi become globally popular?

With a name like Xiaomi, the brand’s global recognition might seem counter intuitive. It is not pronounced the way many Western readers might expect, and the name, which literally means “millet”, is a reference to the idiom “millet plus rifles” coined by revolutionary Chinese leader Mao Zedong, giving the brand an everyman appeal at home but not much cachet overseas.

Yet Xiaomi’s rapid rise in China helped it make one of its most consequential moves in 2013: hiring Hugo Barra.

Before Xiaomi poached him, Barra was vice-president of product management for Android at Google. His title at Xiaomi was vice-president of international, serving as the global face of the Chinese brand.

Barra was responsible for choosing new markets to expand to, starting with Singapore. But it was India, where millions of people were being brought online for the first time, that became the company’s highest priority.

By the time Barra left Xiaomi in 2017, Xiaomi was the third-most used smartphone brand in India, and today it is No 1, according to numbers from StatCounter.

Xiaomi has also managed to weather a backlash in India against Chinese technology brands better than many of its competitors. This is in part because of some clever marketing, spearheaded by Xiaomi India managing director Manu Kumar Jain, who was hired by Barra.

Xiaomi now promotes its devices as “made in India”, where it assembles many devices sold locally – although many of the components inside those phones are still sourced from China.

During Barra’s tenure, the brand also broke into the top 10 smartphone companies in Europe, where Apple and Samsung devices are much pricier than in the US.

Xiaomi forges ahead of Huawei in global smartphone market

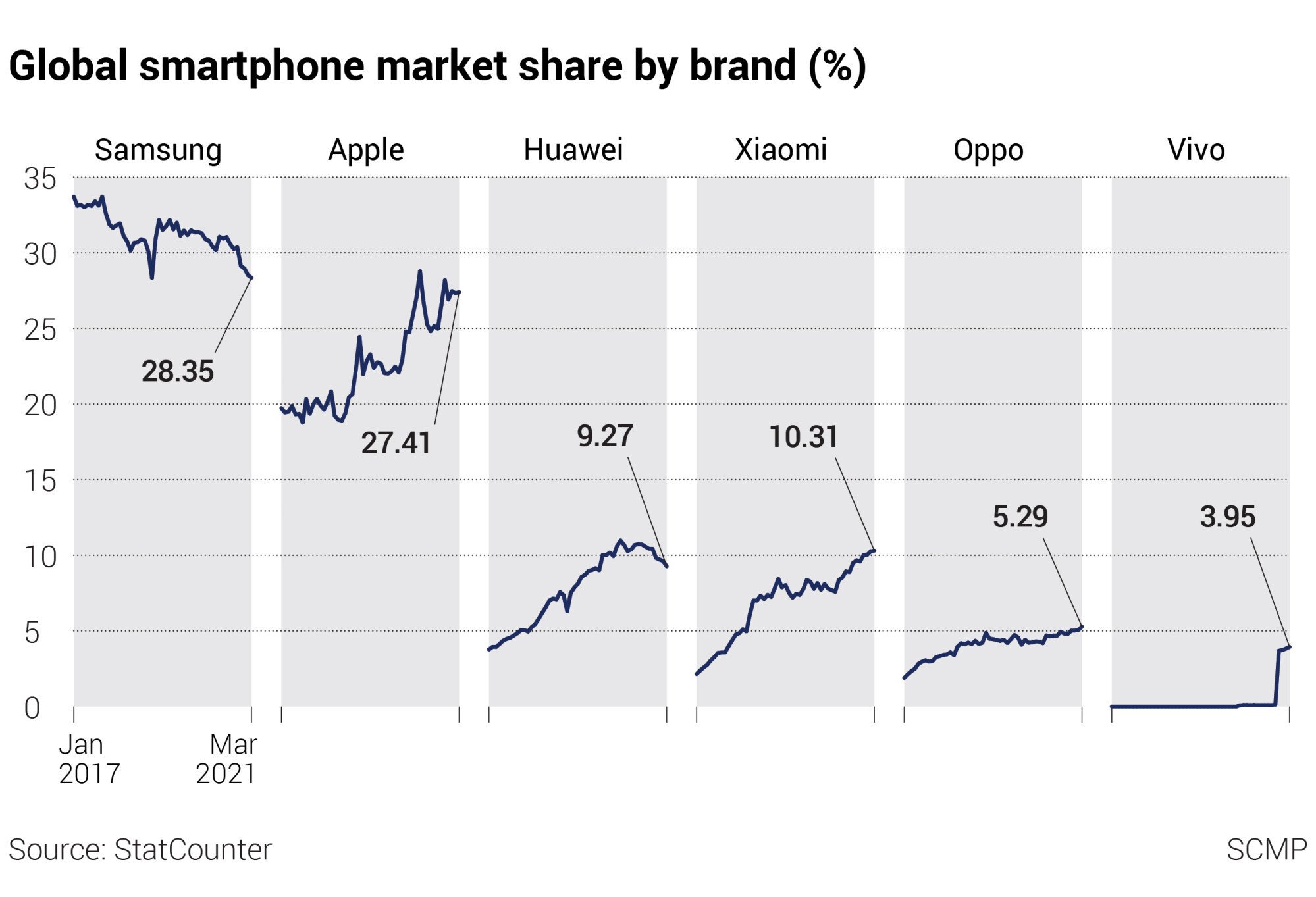

It is now in fourth place behind Samsung, Apple and Huawei, which has seen a sharp decline in shipments globally amid US sanctions, further opening the door for Xiaomi.

Although Barra eventually absconded to Facebook to head its virtual reality efforts, he helped raise Xiaomi’s profile considerably, leaving it in a good position for global growth.

A year after Barra left the company, Xiaomi went public on the Hong Kong exchange amid the ensuing US-China trade war. The company’s debut failed to reach the US$100 billion valuation Lei was hoping for, reaching about half that value.

After an initial dive in its share price, Xiaomi traded at less than half its debut for much of the following year. Despite continued revenue growth, Xiaomi’s stock has largely remained anemic, with the exception of a sharp spike in the beginning of 2021.

Although Xiaomi has not been able to get people excited about owning a piece of the company, consumers are still willing to own its products, as the company has continued to grow both revenues and its global footprint.

As the most recognisable Chinese smartphone brand today with the exception of Huawei, Xiaomi has been taking advantage of the troubles facing its rival, which was cut off from Google apps and services by a US trade blacklist in 2019. In the fourth quarter of 2020, Xiaomi was the third-largest smartphone vendor in the world, behind only Apple and Samsung.

Why is Xiaomi making cars?

Tech companies are piling into the electric vehicle (EV) business, and Xiaomi is no exception. Rivals Baidu and Huawei are already working on their own EV projects, and Apple has also reportedly been eyeing the market for a few years.

Cars are already increasingly giant electronics. In 2017, electronics accounts for 40 per cent of the cost of new vehicles on average, according to Deloitte, up from 20 per cent a decade earlier.

Lei seems to have adopted the view that cars are just larger gadgets. When unveiling Xiaomi’s electric car ambitions, he referred to smart cars as “smartphones with four doors”.

Lei said the company’s first EV will be an SUV costing between 100,000 yuan and 300,000 yuan. By comparison, a Tesla Model 3 starts at about 299,000 yuan in China, while Xpeng Motor’s P7 costs 240,000 yuan.

Electric cars are a new frontier for tech companies. Like the many IoT products Xiaomi already sells, cars are getting smarter, and that is opening the door to tech companies that want to be the brains behind these vehicles.

That could mean more opportunities to sell digital products and services to customers through the vehicles they drive, which they are likely to keep longer than a smartphone.

For some tech companies, getting into the car business could just be making the operating system the car runs on. This has been the approach of Huawei, which has signed up 18 partners to use its 5G HiCar system and has a complete intelligent automotive solution called HI.

Xiaomi boss stakes legacy on EV pursuit after bullish stock, bond run

Xiaomi plans to sell cars under its own brand, but it is not likely to be going it alone. Earlier reports said the company was working with Great Wall Motor, but the carmaker denied the rumours.

While Xiaomi might not yet be prepared to make an entire car itself, it does know how to make a lot of what goes into a smart car. The dashboard of modern electric vehicles are essentially large smartphones. It also works with suppliers of another very important component: batteries.

China dominates the lithium-ion battery market as a leading source of the necessary components. This supply-chain advantage could be one reason Tesla was so eager to get its Shanghai Gigafactory up and running. It could also be an asset for Xiaomi, a Chinese company with a long relationship with local suppliers.

What else has Xiaomi been up to?

Xiaomi remains committed to its ecosystem as it diversifies into new areas and continues to push up market. Beyond EVs, Xiaomi unveiled its most premium TV yet last year: a US$2,000 OLED set.

The company is also trying to break into social media by overhauling its MiTalk messaging app with live audio features, making it work similarly to the viral app Clubhouse, which is now banned in China.

Despite these efforts, and still billing itself as an IoT company, smartphones remain central to Xiaomi’s business strategy. Its phones are also increasingly well received.

The company’s MIUI Android skin, once panned for being riddled with bugs, is now complimented by some reviewers as one of the better options available. Its latest flagship phone, the US$1,000 Mi 11 Ultra, has been favourably compared to the latest iPhones and Galaxy phones.

The company has also signalled that it is committed to bringing 5G connectivity to everyone. Last year, it said all phones from its budget Redmi brand that cost more than US$210 would have 5G onboard.

In recent years, smartphones have made up around 60 per cent of Xiaomi’s revenue, while IoT and lifestyle products have hovered between 25 and 30 per cent. Internet services have still not topped 10 per cent of revenue for a full year.

Fortunately for Xiaomi, it bet on a good product category from its inception. With Huawei’s fortunes looking dire, Xiaomi’s position as China’s reigning smartphone king is currently unchallenged.