Tom Brady had questions—so, so many questions. They arrived early on several consecutive mornings in October 2019, delivered before sunrise, over email. Usually, this process works the other way. But, in this instance, Brady was the one writing, which made for an odd twist: He had questions he needed answered. And what he asked opened a window into his brain, how it processed the task in front of him, why details mattered because of how they added up to something greater, a lot more.

Already an NFL superstar, entrepreneur, documentarian, celebrity pitchman and recovery guru, this particular task was to pen the foreword for the book I co-authored with Jim Gray, Talking to GOATs: The Moments You Remember and the Stories You Never Heard, a memoir of the sportscaster’s life and career. With apologies to book editors, this is generally a perfunctory exercise, where the name matters more than the words, which are typically written quickly with minimal effort.

By now, the world already knows Tom Brady does not do “minimal effort.” He wanted to bat around concepts. He wanted to see an outline. Then he wanted to read the proposal. Then he wanted to read the chapters that had been completed. Two days later after his final inquiry, another email arrived, titled “BradyGray forward.” Other than the header, he filed a clean piece, introducing the nickname Jack Nicholson gave Gray long ago—Scratchy. “You just keep scratchin’,” the Academy Award–winning actor would say to Gray over almost two decades of interactions and their mutual love of golf. Editing Brady was like coaching him. It’s best to step back, admire and get the hell out of the way.

Two things Brady wrote stand out now after the quarterback officially announced his retirement via Instagram on Tuesday, after 22 NFL seasons and seven Super Bowl rings crowding out the fingers on his hands. The first is he took information from the rest of the book and applied it to his personal experience with the subject, stitching together facts, teasing stories to come and painting a vivid picture of a friendship and how it came to be. Let’s just say Brady wrote a lot better than anyone at Sports Illustrated could play quarterback. The second is the open to his seventh—of course, seventh—paragraph:

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

To my mind, it’s not what people do in their 20s that leads to greatness, or a lasting legacy. It’s what they keep doing, year after year, at a consistently high level.

That’s Brady. Not the Instagram followers. Not the supermodel wife, Gisele Bündchen. Not the worldwide fame, the handful of controversies he confronted, the lives he changed, the records he set or the older people he inspired. Not even the Super Bowl rings. No, Brady is process, him doing the same things, year after year, at a consistently high level. That he developed his process long before every team in every sport created their own, while other elite athletes followed suit with individual teams of recovery specialists, only speaks to Brady’s influence—and not just in the NFL, or in sports, but also in a wider sense, the kind that leads to greatness, or a lasting legacy.

I first began to understand what drove Brady in 2014, when then editor Chris Stone assigned me to a Brady profile roughly nine months into my first year at SI. Touching down in Boston on a red-eye from Seattle, I drove straight to the TB12 Performance Recovery Center, the space Brady and his body coach, Alex Guerrero, had opened a short walk from Gillette Stadium.

Guerrero revealed the depths of Brady’s routines that morning, all the pliability, recovery pajamas and resistance bands he is known for now. He also mentioned a snack Brady preferred, the kind of detail that could make Brady seem robotic, deliberate, obsessed: avocado ice cream. Still waiting on that royalty check. Brady laughed at the detail but not the sentiment. Where most truly elite athletes take great lengths to emphasize they are more than their lucrative day jobs that mere mortals would kill for, Brady dropped the whole façade. Football did define him. “Football isn’t what Tom does—football is Tom,” Guerrero said then and firmly. “This is who he is.”

Asked how long he wanted to play, Brady, then in his 15th season with the Patriots, had not yet settled on the number he would trot out in subsequent years (age 45). Instead, he answered in one word: forever.

Three years later, in 2017, Brady’s routines defined him. They were starting to define sports, too, copycat proof of his vast and spreading impact. TB12 was no longer a name slapped onto a facility Brady could access easily from his “office” down the block; it was a brand that would become a book and explain the ethos of an icon defined by time. Time stolen, turned back and utilized.

I spent a few weeks that spring talking about Brady with older athletes across many sports, from UFC champion Daniel Cormier to Bruins defenseman Zdeno Chara to NASCAR driver Jimmie Johnson. One anecdote stood out. It came from Didier Drogba, the soccer superstar, at that point the fourth-leading goal scorer in Chelsea’s storied Premier League history. Drogba had met Brady the year before at the Canadian Grand Prix in Montreal after striking up a conversation on the infield. As Formula One cars zoomed past at more than 200 miles an hour, two athletes were nerding out on process and forgot why they were there. They compared notes on their stretching routines to improve muscle elasticity in what Drogba referred to then as "the same language”—known to only a handful of athletes of their respective calibers on earth. When Brady asked about endurance training, Drogba told him the key was not more workouts but more rest. Their bodies were like race cars, he said, motioning to the track (and perhaps never having seen Brady run at the NFL scouting combine).

Near the end of the interview, Drogba delivered a vague clue: He and Brady had made some sort of bet in Montreal; their wager centered on championships and longevity. But he wouldn’t say exactly what it was. I tried to glean more details, through Brady, his confidants and relatives. No one knew. Or no one would say. I figured I’d ask him whenever he retired.

Thing is, he never retired. He kept coming back. He went to Tampa in 2020 and won another Super Bowl last February. He set career quarterback records for passing yards, completions, touchdown passes, games started and Pro Bowl nods. He amassed a number of avocado ice cream references that will never be broken. He never played for a team with a losing season. He won Super Bowls in three decades, with two franchises—and lost three along the way. He dealt with Gates—from the serious (Spygate) to the absurd (Deflategate)—health issues (his mother Galynn’s cancer) and the inevitable point in every season when half of pro football pronounced he was done, finished and, finally, too old. He kept coming back, remember? Kept winning. Kept raising the Lombardi Trophy over his chiseled chin.

Only now, his children were getting older and his life was changing, along with the perception of him and—way more important—his perception of himself and what he wanted. He became more of a mentor to his teammates, an older uncle to some, a father figure to others, a de facto assistant personnel executive and coach. He wanted to spend more time at home. Would he find that time?

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

He stuck around so long it became impossible to define him by any one specific moment, trend or thing. He was NFL history—from the tuck rule, to his records, to his longevity, his career lasting well past the day last August when he turned 44. He was offensive evolution, in both the surgeon’s accuracy quarterbacks would come to display and the explosion in passing numbers that didn’t start with him but that he elevated, and then elevated more. He was rule changes, for acceptable air pressure in footballs, how officials handled quarterbacks and how—and how low—the defenders could (legally) hit them. He defined decades of pro football with every element that makes the NFL the NFL: rivalries (hello Colts!), villains (hello Patriots!) and controversies (just ask Twitter).

More recently, Brady continued the trend of elite-but-older athletes finishing their careers in other places for other teams. The difference between him and them was the same as the difference between him and those who hung on with the same team: He didn’t just keep coming back; he kept winning, kept dominating, kept slinging.

Compared to other older quarterbacks, Brady did not walk away because his skills diminished. He did not retire because of a decision dictated by a growing tally of birthday candles and introductory physics classes. He wasn’t Peyton Manning at the end in Denver, throwing wobblers as strong defense led the Broncos to a title. He wasn’t John Elway in the later years, also in Denver, reliant on an elite running game to triumph. He wasn’t Joe Montana after Montana headed to Kansas City, good but injured in the playoffs. No, not Brady, not after years of analysts predicting his drop-off or claiming they had uncovered evidence of his decline.

Barring a Favre-ian change of mind in the months ahead, Brady’s final touchdown throw should be obvious, everlasting proof. The backdrop: Two weeks ago, on second-and-7, late fourth quarter, down 14 against the Rams—the game and season all but over. Brady took the snap in the shotgun and dropped further back with typically precise footwork, as smooth as a ballroom dancer. His defensive nemesis, Von Miller, came streaking around the edge. Help arrived, allowing the old man at quarterback to step into his throw and heave the ball down field. The pass arced so far and high, the ball disappeared from the view of the camera that was supposed to track it. According to ESPN Stats and Info, the pass traveled 56.7 yards, following a parabola and dropping into the exact spot where wideout Mike Evans was headed on a go route, a step ahead of All-Pro corner Jalen Ramsey, and landing in Evans’ hands for an easy score. According to the same ESPN service, Brady attempted that particular pass despite a measly completion probability of 26.4 percent.

Think about that. Elway retired at 38; Manning, 40; Montana, 38. None threw that kind of poetic masterpiece in their final season, let alone for their final touchdown, let alone at 44 years old. None provided that one, final emphatic answer to his critics.

It’s what they keep doing, year after year, at a consistently high level.

Brian Lanker/Sports Illustrated

Last February, Brady lifted Tampa Bay into the same place he always lifted teams: to the Super Bowl, held in the Bucs’ home stadium—another NFL first. It seemed fair (and fantastical) to wonder: Maybe he would really play forever. As part of our reporting for the Super Bowl LV cover story, reporter Jenny Vrentas and I spoke with aging specialists, goat farmers, Hall of Famers and a certain soccer star who still would not reveal the answer to the clue he had provided in 2017. Bruce Arians, Brady’s coach in Tampa, told us what Brady had not said out loud. “Tom is playing for his teammates right now,” he said. “He wants those guys to experience what he’s experienced six times. I think personally, too, he’s making a statement. You know? It wasn’t all coach [Bill] Belichick.”

That was Brady, too: still driven by his place in history, even with it secured, by slights real and imagined—not by what he had done but how he did it, day after day, year after year, season after season. Finally, he settled in front of a laptop screen at Bucs headquarters one afternoon. He started with some small talk, exchanging pleasantries, how’s the family. After all of that, I finally had my chance. “What did you say to Drogba on that infield?”

Turns out, Drogba asked the same question as everyone else in the sports world. “How long do you plan to play?”

“I don’t know,” Brady recalled telling him. “I just want to keep going. I just want to win.”

Drogba reacted like a reasonable person would be expected to. Come on? How many championships? When’s the expiration date on forever? At that point, Brady had won four Super Bowls, a number that only a few of the best-of-the-best NFL luminaries ever grasped. That number seems small now, in hindsight. Brady made it small because he almost doubled it. That afternoon, he told Drogba he felt great and one number mattered to him more than any other: six, or the tally of titles seized by Michael Jordan. “If I get a sixth,” Brady said, “I can retire as a GOAT.”

He got a fifth. And a sixth. And, on that afternoon, over Zoom, he eyed the number the soccer star had spit back at him.

“If you really want to be the GOAT, you gotta try for seven,” Drogba had said.

Brady laughed then but thought, “Man, you’re f---ing crazy.” Then he beat Drew Brees and the Saints in the Buccaneers’ playoff opener. Then he toppled Aaron Rodgers and the Packers in the divisional round. Then he dominated the Chiefs and Patrick Mahomes in the Super Bowl. And, after out-performing those three future Hall of Fame contemporaries, he came back. He still wanted to win; but, more than that, he wanted to compete and train, year after year, at a consistently high level.

That he chose to return this season, winning SI’s Sportsperson of the Year for the second time and leading the hobbled Bucs back to the divisional round, was less surprising than the moment he decided to step away. Sure, pundits, observers and his inner circle knew this day would eventually come. They understood that “forever” wasn’t literal beyond his legacy and season-by-season approach. The forever really happens now.

After he stated numerous times he planned to play until age 45, needing to play only one game next season to achieve it, that’s when he retired—not when everyone predicted he would, but when most believed, until recently, he would return. Perhaps, it was a fitting end to T.B.E. or—with apologies to Floyd Mayweather Jr.—The Brady Era.

In the coming days, there will be plenty of words typed about his legacy, his impact on how we view the aging process, what’s possible when you’re supposed to head off to the golf course and reminisce about the glory days.

But that’s not the most fascinating part of all of this. What is? Tom Brady made the spectacular routine, branched into all sorts of business, evolved from lovable to disdained (or adored) to respected (and sorta lovable again). Maybe he’ll take up writing in retirement. Regardless, what made him and all that possible was he made it all look routine, almost boring. It was the toiling in the shadows, the strawberries in the garbage, the transformation of body and mind. It’s what they keep doing, year after year, at a consistently high level, that led to greatness, a lasting legacy.

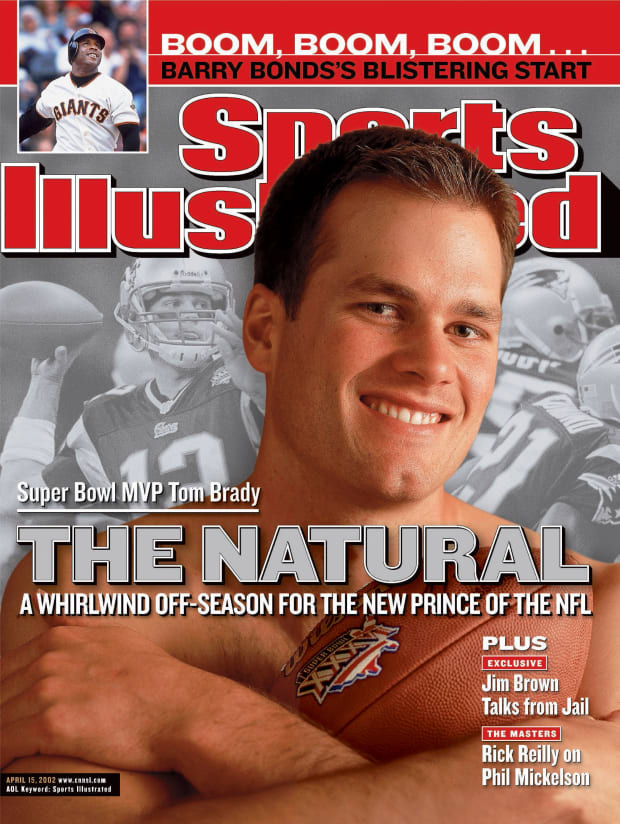

- Photos: Every Tom Brady Sports Illustrated cover

- Sportsperson Outtakes: Tom Brady, In His Own Words

- SI Vault: The Ultimate Teammate

- Tom Brady's Exit, And The Void That Comes With It