The Rangers and Diamondbacks combined to throw 1,490 pitches in the World Series. They did so without a single pitch timer violation.

You didn’t notice? That’s the point.

The 119th World Series was unlike any of the 118 that came before it. It was the first one in which MLB decided its champion while playing with a clock, also known as the pitch timer, also known as the greatest product innovation to a baseball game since Harry M. Stevens sold hot dogs at the Polo Grounds on a cold Opening Day in 1901 (or so the legend goes).

And you didn’t even notice the clock.

Why? It was irrelevant. Fox made the proper decision not to show it on the screen. (Discloser: I am part of the broadcast team.) The pitch timer has become such an accepted part of baseball that it literally faded out of sight.

Watch MLB with Fubo. Start your free trial today.

Jayne Kamin-Oncea/USA TODAY Sports

Take a bow, players and umpires (the maestros of starting the timer with that twirl-of-the-hand flourish). You made such a swift transition to a faster-paced game that nobody said anything about the pitch timer over the seven days of the first World Series played with a clock. Amazing, especially when you recall all the fuss about it in spring training.

“I think it’s verification that the clock helps players play the game in its best form,” commissioner Rob Manfred says. “They deserve credit. They have adjusted very well. I think the umpires used really good judgment as far as when to be really firm about the rules and when to use discretion.

“The season and the postseason are validation that we have the rules right and they make the game better for the fans.”

The pitch timer in the postseason was a home run, which you can see in a stunning comparison here of the past two World Series walk-off homers. The postseason data and the aesthetics were immensely improved by the pitch timer. Let’s start with the data:

Postseason Pace of Play

| G | RPG | 9-Inn. Time of Game | |

|---|---|---|---|

2023 |

41 |

8.2 |

3:02 |

2022 |

40 |

7.3 |

3:23 |

2021 |

37 |

8.6 |

3:37 |

The Highlights:

- Postseason games this year were 21 minutes shorter than last year—with a 12% increase in runs.

- The games this year shaved 35 minutes off game times from two years ago.

- Three World Series games were played in less than three hours—only the second time that’s happened in 27 years and the first time since 2006.

- Every nine-inning World Series game was played in less than 3:20, the first time that has happened this century. It broke a streak of 23 straight years with at least one nine-inning game taking 3:20 or more, with an average of 3.3 equivalent showings of The Irishman every World Series.

- There were 11,829 pitches this postseason…and seven pitch timer violations. It works out to one violation every six games, or about one every 1,700 pitches.

- The four-hour nine-inning game is dead. In the past 10 seasons, there were 41 nine-inning postseason games that lasted four hours, including at least one every year. This year? None.

Postseason Game Play

| SB Att. | SB% | SO% | Avg. | BABIP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2023 |

1.6 |

85.1% |

23.8% |

.241 |

.288 |

2022 |

1.1 |

77.3% |

27.0% |

.211 |

.263 |

The Highlights:

- Stolen base attempts increased by 45%.

- The success rate in the postseason (85.1%) was higher than in the regular season (80.2%), which was a record high.

- Without shifts, the 25-point increase in batting average on balls in play was driven by a 39-point increase by lefthanded hitters, up from a 14-point increase in the regular season.

People resist change. It’s human nature. Remember when the timer and the new rules debuted in spring training? A spring game between the Braves and Red Sox ended in a 6–6 tie on a pitch timer violation on the batter, Atlanta prospect Cal Conley, with the bases loaded and a full count. Immediately people howled about such a scenario sullying the World Series.

The more games they played, the more the players adjusted. The rate of violations per game dropped steadily throughout the year. It went from .87 in the first 100 games down to .17 in the last 100. Sixty-seven percent of all games had no violations.

Still, some among the players, fans and media warned that postseason games “needed” more time on the clock than the regular season standards (15 seconds with the bases empty; 20 seconds with a runner). The argument was that the clock would rob postseason moments of “drama.” It was nonsense, which I proved when I took one of the most dramatic at-bats in history—Kirk Gibson’s home run off Dennis Eckersley in 1988 World Series Game 1—and showed the eight-pitch at bat included no violations of a theoretical 20-second clock.

The clock doesn’t force players to play unnecessarily fast; it returns the game to a pace that was common in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

The dawdling that infected the game was a more recent trend that added slog, not drama. Still, upon canvassing opinions from players this summer, Manfred, through his Competition Committee, would have to decide whether to keep the same regular season rules in the postseason or add time to the clock. He chose the former.

“I thought a lot about the postseason just because in talking to players throughout the year it was raised frequently,” Manfred says. “We talked about it internally as well. And there were two things that convinced me to leave the clock alone.

“Number one, I do think people generally are reluctant to play the postseason under different rules. It doesn’t make a lot of sense. And number two, players had made such a great adjustment to the timer that we had some feeling of confidence it would not be a problem.”

He was right. Consider Justin Verlander. He is 40 years old. He has been pitching in the majors for 18 years. And yet there he was, winning ALCS Game 5 in Texas, comfortably adjusted to the pitch timer. Before each pitch, the Astros ace would get his sign from catcher Martín Maldonado via PitchCom, the wireless communication device, then take a quick sideways glance at the pitch clock, halfway between the dugout and home plate, to gauge how much time he had remaining.

It’s what players do: they adjust, whether it’s the slide rule at second base, the anti-collision rule at home, PitchCom, a new batting stance, a new pitch, etc. Baseball is fluid and so must be those who play it.

As for the aesthetics, if you’re a fan, this is the kind of baseball that you wanted, at least as far as years of polling by MLB has shown. You can reduce this new era of baseball to five words: more action over less time.

Did you notice the “baseball is too slow” trope was nowhere to be heard this October? People always need something to complain about, so the bellyaching this year was about the playoff format, in which the top two division winners earned byes—and five days off. The Braves, Dodgers and Orioles all were bounced in the LDS with a combined record of 1–9, so people blamed it on the rest rather than their opponents, the Phillies, Diamondbacks and Rangers.

Stop, people. It didn’t bother the Astros (3–1 vs. Minnesota). And as Texas manager Bruce Bochy said, “I’d much rather have the days off than have to play on the road, best of three.” Every manager would say the same thing, which tells you the format is not a problem. It’s called baseball, folks. Things happen.

“We always look back at what goes on in the season,” Manfred says about a review of the format. “It always happens among ownership and I’m sure it will happen with the Competition Committee.

“I want to be clear about this: I think the format has worked out well. I really do. There is enough incentive to the division winners. For the players, playing every day is hard. I understand the layoff issue. I’m going to steal from C.C. Sabathia and repeat that if it comes down to having to win two out of three on the road or having days off, they’ll take the days off.

“That’s number one. Two, this is only the second year [of the format]. Teams are going to figure out what to do as far as managing the issue.

“Let me say I’m always prepared to have the conversation. But unpredictability in the postseason is not a bad thing. If you’re just going after the same result you got after 162 games, you might as well go home in September.”

Were we supposed to get the Braves vs. Orioles in the World Series? Do you want competitive balance (which people rightfully squawk about when it comes to payrolls) or do you want 1949–58, when the three New York teams (Yankees, Dodgers, Giants) won nine of the 10 titles and occupied 16 of the 20 World Series slots? Half the teams in baseball have played in the past 10 World Series; nine franchises have won those 10 titles.

By the get-the-top-seeds-through crowd thinking, the Rangers should never have beaten the Orioles. That’s baloney. Texas, actually, was in first place more days than Baltimore (160–77). The two teams split their season series. Texas scored 74 more runs than Baltimore. It had a better run differential by 36. Though Baltimore won 101 games and Texas 90, based on runs scored and allowed the Rangers’ expected win total was higher (96–94). The point is that the difference between the two clubs was marginal.

And then baseball happened. When they played three games in October, Texas won them all by a combined score of 21–11. The Rangers went 11–0 on the road in the postseason. To argue that such a team should have lost to Baltimore in the first round is folly. Texas earned it.

The Rangers were so good they robbed us of the drama of a long World Series. We got only one possible elimination game, which is the height of Fall Classic tension. But what we did get all October were more balls in play, more runs and more hits over less time—and more people who had to go to school or work the next day who could be awake for the end of games.

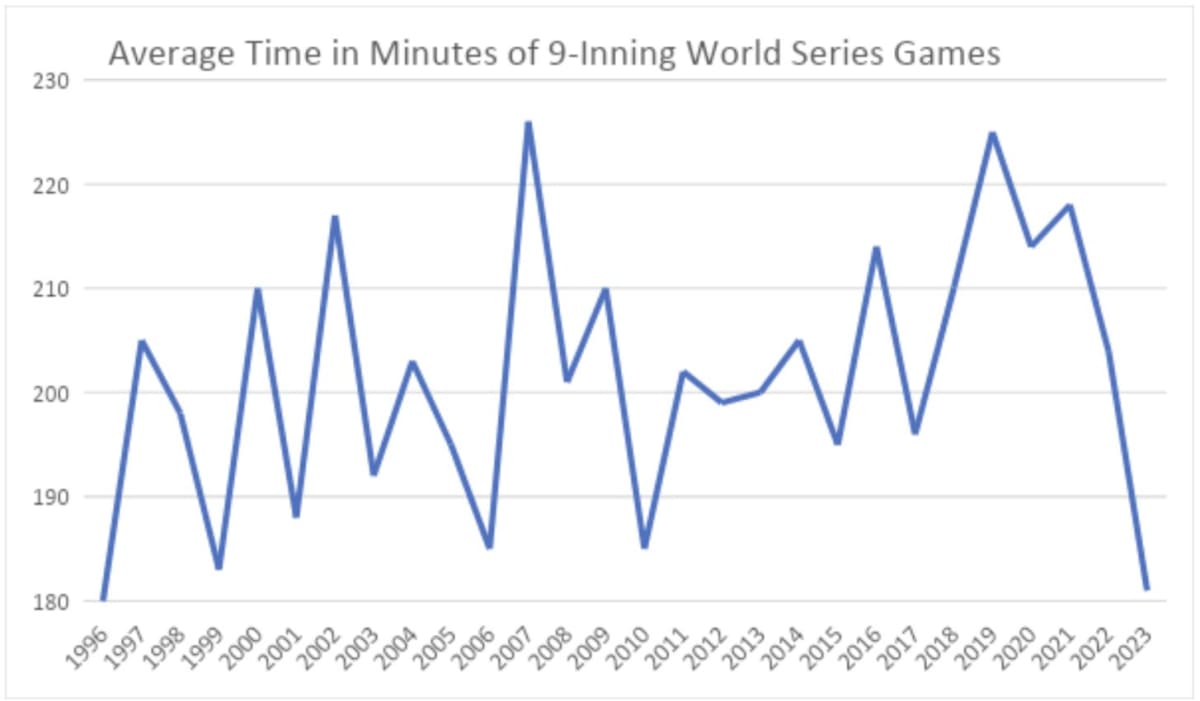

Finally, here is a chart with the average time of nine-inning World Series games by year. What you see is a steady rise in slower games from 2010 to 2021, in which 33 minutes of nothingness was added to your typical World Series game, which is when those “baseball is boring” memes took root. What the pitch timer did was excise that half hour or so of nothingness in a virtual snap of the fingers. In one year, it returned the World Series to what it was in 1996, without controversy, without a violation and probably without you even noticing it.