When the Trump administration announced in February 2025 that it was cutting 10% of staff at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it seemed that a small but storied program within it called the Epidemic Intelligence Service – also known as the CDC’s disease detectives – would also be cut. A few days later, the program was reinstated. And in March, Epidemic Intelligence Service officers traveled to Texas to support the state’s public health officials in fighting the ongoing measles epidemic.

But after another massive upheaval at the CDC in April, the unit’s future is uncertain. As of now, applications for the program’s next round of fellows has been postponed.

The Epidemic Intelligence Service is a dynamic crisis response team. Just as firefighters rush into burning buildings to save lives, this team’s specialists mobilize both domestically and internationally to help curb disease outbreaks. But first and foremost, it is a training program that has produced some of the most highly trained and regarded public health experts in the country who have gone on to work at local and state public health offices, academic departments and international health organizations.

We are public health experts – one an experienced professor who served in the Epidemic Intelligence Service from 1994-1996, and the other an early career trainee who was accepted to its incoming class of 2025-2027. Although it’s not clear how the administration will enact its new vision for the CDC, we hope a continued urgency to identify and fight infectious disease threats – the essence of the Epidemic Intelligence Service – remains a national priority.

A program rooted in national security

The Epidemic Intelligence Service is a two-year fellowship open to physicians, scientists and other health professionals. The program accepts 50 to 80 people each year.

The Epidemic Intelligence Service was founded in 1951, just five years after the launch of the CDC, in response to Cold War-era concerns about biological warfare. Alexander Langmuir, its founder, was the CDC’s chief epidemiologist and has often been called the father of shoe-leather epidemiology – on-the-ground, out-of-the-office disease investigation through extensive field work and engagement with affected populations.

In a report announcing the unit’s establishment, Langmuir and a colleague wrote that one of the “problems that would emerge in the event of biological warfare attacks” was “the dearth of trained epidemiologists.” They recognized the urgent need for a specialized team capable of rapidly identifying and responding to potential bioterrorism threats.

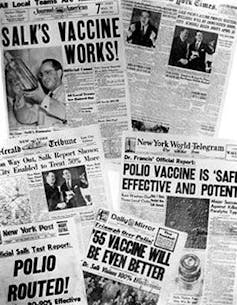

The new division soon evolved to address a wide range of civilian public health threats. In 1955, as one of its first major actions, the program’s officers were tasked with investigating an outbreak of polio in children that started just as the first mass vaccination campaign against the disease launched. Within weeks, Epidemic Intelligence Service officers helped trace the outbreak to a few batches of a vaccine manufactured by a California company called Cutter Laboratories in which the virus had not been properly killed. The incident led to increased safety regulations in vaccine production and boosted public confidence, paving the way to eliminating polio from the U.S. in the ensuing decades.

The Epidemic Intelligence Service has led the way in tackling many of the most historically significant outbreaks of the past 75 years. Starting in 1966, the unit’s officers were deployed to West Africa to assist in a worldwide smallpox eradication campaign that laid the groundwork for eliminating the disease 13 years later. In 1976, the disease detectives were sent to investigate an outbreak in Philadelphia of a mysterious deadly illness. They helped to characterize what would eventually be known as Legionnaires’ disease, a previously unknown bacterial cause of pneumonia.

And in 1981, a tip from an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer serving in the Los Angeles County Health Department led to the first description of a new disease that would become the global epidemic of HIV-AIDS. The program’s officers went on to help lead foundational studies on prevalence, prevention and treatment of AIDS around the world.

Beyond vaccines and immunization

Even from its earliest days, vaccine-preventable and infectious diseases were far from the Epidemic Intelligence Service’s only focus. During the program’s first 15 years, its officers were involved in a wide swath of epidemiological investigations in areas including lead paint exposure, a cancer cluster’s connection to birth defects, family planning practices and famine relief.

These activities established the group’s priorities of addressing chronic diseases and population health – goals that have also driven its involvement in disaster response efforts, including hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria and Katrina, as well as the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

The Epidemic Intelligence Service has also played a key role in keeping the nation’s food supply safe. It investigates major outbreaks of foodborne illnesses, helping to identify which foods are implicated so that contaminated products are removed from shelves and disseminating investigation findings that inform food safety policy. For example, officers investigated a 1993 outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 linked to undercooked hamburgers at several Jack in the Box restaurants. The outbreak sickened more than 700 people and resulted in the deaths of four children. It also led to major food safety reforms including expanded meat and poultry inspection nationwide.

A legacy of impact

The importance of an expert, nimble team of disease detectives has only increased. Over the past few years, Epidemic Intelligence Service officers have responded to countless public health threats.

The program’s officers were involved at every stage of the COVID-19 pandemic response, conducting outbreak investigations on cruise ships, in prisons and in many other settings. They investigated the outbreak of monkeypox in the U.S. in 2022. Most recently they have investigated cases of avian influenza and are working to help describe and control the ongoing measles outbreak in Texas.

Perhaps the Epidemic Intelligence Service’s most significant legacy has been in building a worldwide network of deep epidemiological expertise. To date, the program has trained more than 4,000 disease detectives, and its officers have collectively conducted thousands of outbreak investigations.

The unit’s impact has been global. It has been called in to investigate outbreaks on six continents and has served as a model for epidemiology programs developed in dozens of countries.

All of these activities, at home and abroad, have shaped health policy in crucial ways that in turn protect people’s health. It is increasingly clear that disease outbreaks will continue to occur in the U.S. and abroad. In our view, the Epidemic Intelligence Service’s history provides rich evidence of its value.

I am currently a member of the EIS Alumni Association Executive Committee.

Casey Luc does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.