After 65 years, Philadelphia police announced in December 2022 that they had identified the remains of Joseph Augustus Zarelli, a 4-year-old boy who was murdered in 1957. Because no one had ever come forward to reliably identify Joseph, he became “America’s Unknown Child,” a moniker that captured the tragic anonymity of his early death.

Recent advances in DNA analysis and forensic genealogy provided the needed breakthrough to build a genetic profile that connected the boy to surviving members of his mother’s family. But linking that genetic profile to Joseph’s identity required finding his name, a piece of information stored alongside his mother’s on his nearly 70-year-old birth record in the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s vital records system.

While the revolutionary science of genetic genealogy has received well-earned recognition for its contribution to solving this long-standing mystery, the integral role of the more staid vital records system has mostly gone unnoticed.

Vital records are the stalwart administrative backdrop to life’s milestone events: birth, adoption, marriage, divorce and death. When a child is born in the U.S., the parents and hospital staff complete and sign a certificate of live birth that includes nearly 60 questions about the parents, the pregnancy and the newborn. A local registrar issues a formal birth certificate upon receiving the record as proof of a live birth.

Other vital events follow a similar process. Collectively, the U.S. vital records system comprises records of hundreds of millions of events dating back to the beginning of the 20th century.

As a family demographer, I use information from these vital records to understand how childbirth, marriage and divorce are changing in the United States over time. The scope and quality of these records reflect remarkable administrative coordination from the local to the national level, but examples from other countries illustrate how much more the records could yet tell us.

Vital records mark unique events

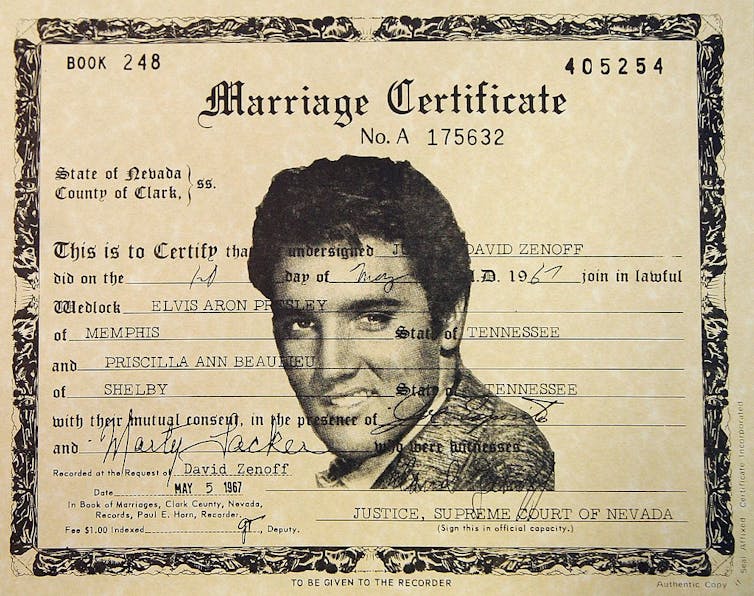

Originally, vital records were intended to publicly register events in order to legally recognize the status of the people involved. The two people named on a valid marriage certificate, for example, share the legal protections and obligations of marriage until death or divorce. But over time, vital records have also come to serve as proof of identity. For both purposes, the integrity of the vital records system is critical.

Practically speaking, the system requires a perfect symmetry between people and events. Every recorded event needs to be associated with a unique person or pair of people, in the case of marriage and divorce, and every person or pair needs to be associated with a unique recorded event. Because of this singularity, a valid birth certificate is required as proof of an individual’s unique identity to obtain a Social Security card, driver’s license or passport.

The uniqueness of each event also underlies how birth, marriage, divorce and death rates are calculated. Double-counted events will artificially inflate these rates, while uncounted events will reduce them. Valid rates are important because governments and businesses rely on accurate measures of population change for planning and investment.

America’s local approach to vital records

In the U.S., the vital records system isn’t a single entity. Rather, there is a collection of state and local vital records offices operating independently but in cooperation with the federal government.

Each U.S. state and territory, as well as New York City and Washington, D.C., is its own vital registration jurisdiction, amounting to 57 areas in all. And within each jurisdiction, local offices receive and process records and issue certificates. Nationally there are over 6,000 local registrar offices issuing birth certificates in the city or county where a birth occurred.

In nearly all states, marriage licenses and divorce decrees are certified and filed at the courthouse in the county where the event happened. This local registration system explains why Nevada has the highest marriage rate in the nation: of the over 77,000 marriage licenses issued in 2021 in Clark County – home to Las Vegas, America’s wedding capital – more than 60,000 couples provided a home mailing address outside of Nevada.

This highly decentralized approach has at least two significant implications. First, because different agencies are responsible for recording different events, there is no straightforward way to assemble an administrative profile for an individual over a lifetime. This challenge is further complicated when records are stored in different jurisdictions as people move and experience events in different places. Name changes – for example, through marriage – and inconsistencies in spellings, dates or other details also potentially impede record matching.

Second, in the absence of a single national repository for vital records, it takes substantial coordination to produce national statistics about vital events. Currently, U.S. jurisdictions send individual-level birth and death records to the National Center for Health Statistics annually, and these records provide the basis for national birth and death statistics overall, including demographic characteristics like age, sex, race and ethnicity. This coordination is costly, time-consuming and often delayed.

In part because of the administrative burden, states stopped sending detailed individual-level marriage and divorce records to the National Center for Health Statistics in 1995, and now provide only annual counts of these events. As a result, the only accessible way to examine national demographic patterns in marriage or divorce is through surveys, which are subject to nonresponse and reporting errors.

Centralized approaches to vital recordkeeping

In contrast to America’s decentralized system, many countries in Northern Europe have centralized and integrated the collection and maintenance of administrative records related not only to vital events but also to circumstances like change in residence, employment and health care. This approach ensures that residents are continuously registered to receive mail, vote, pay taxes, enroll in school and receive benefits such as housing subsidies at the correct address. It also means that public agencies have full information about their population to inform planning and budgeting.

A centralized system also facilitates rapid turnaround of population statistics. At peak periods during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the U.S. lagged behind many other countries in estimating national death rates as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention awaited reported counts from public health offices in individual states overwhelmed by the pace and volume of deaths.

Vital records integrated with population register data also allow social scientists, epidemiologists and other researchers to use deidentified linked records to study how early life conditions shape an individual’s life over time. Using linked records from the Netherlands, for example, researchers have demonstrated that children who were in utero during the 1944 Dutch famine were more likely to have health problems throughout their lives than those born earlier or later.

The U.S. has made some progress toward developing a more centralized and integrated vital records system. A national file linking births to infant deaths has helped scientists study how risk factors like preterm birth and low birth weight contribute to infant mortality. And public health and medical research studies can obtain cause of death information for participants in the National Death Index, a compilation over 100 million death records since 1979.

But further progress is unlikely to happen any time soon. The current system, while cumbersome and incomplete, is well established and reliable. And at a time when the majority of Americans lack trust in government, there is little political will or public enthusiasm for a change.

For Joseph Zarelli, the durability of the local vital records system in Philadelphia was enough to answer a question that went unanswered for 65 years: A certificate of live birth registered in 1953 reconnected America’s Unknown Child to his name.

Paula Fomby receives funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.