It’s testament to the covert, simmering influence Gary Numan has wielded over musicians - electronic or otherwise - for almost five decades now that many readers might sooner recognise some of his most iconic synth-laden hooks from their deployment in more contemporary music.

The Sugababes’ repurposing of, more or less, the whole instrumental track of Are Friends Electric? for the song Freak Like Me gifted the pop trio one of their first number one, while Basement Jaxx’s sampling of the unmistakable, pulse-width modulated three-note melody of M.E. provided the core of hit single Where’s Your Head At?. Even Wu-Tang Clan’s GZA repurposed Films for 2013’s Life Is A Movie, while J Dilla’s own take on Cars appearing on his 2016 album The Diary— only the lyric is playfully changed to "Trucks".

Of course, Are Friends Electric? is not, strictly speaking, a Gary Numan song. Credited to Gary Numan & Tubeway Army, it appeared on the band’s second album, 1979’s Replicas. Are Friends Electric? became the band’s first number one hit and helped send Replicas to the top of the UK album chart.

In the corner of the studio control room, Numan spotted something he hadn’t come across before: a Moog Minimoog Model D synthesiser

The mammoth Minimoog synth that constitutes the heart of the song has by now taken on a near-mythological association with Numan; his epiphanic discovery of the instrument paving the way for a trailblazing career epitomised by the sonic explorations of The Pleasure Principle.

That discovery came shortly after Numan entered the studio with the then-guitar band Tubeway Army to record their eponymous first album. “I’d just been signed and I’d written all of these punk songs, but my heart wasn’t really in it,” he would later tell The Quietus. In the corner of the studio control room, Numan spotted something he hadn’t come across before: a Moog Minimoog Model D synthesiser.

“I’d never seen one before. I’m pretty geeky so I was fascinated by it,” Numan said. “I didn’t know how to set the Minimoog up, so I just pressed a key for whatever it was set on, and it made that famous Moog sound, that famous low growl and the room vibrated. It was the most powerful thing. It was like an earthquake and I just loved it. And before the band was even finished setting up the gear I was in there working on changing the songs we’d arrived with into pseudo-electronic songs.”

"It was the most powerful thing. It was like an earthquake and I just loved it"

Numan was convinced he had hit a winning formula, but Martin Mills of Numan’s label, Beggars Banquet, was hesitant. A heated meeting ensued, and finally Numan was given the green light to proceed with the Tubeway Army album, which was released in November 1978. Bridging the gap between the driving, Ramones-esque post-punk of early singles like That’s Too Bad and a burgeoning brand of synth-pop, the album saw a modest release of a few thousand copies in the first instance (with its original cover earning it the unofficial title of The Blue Album) and a subsequent reissue the following year in the wake of Replicas’ success, which sported a new cover image of Numan’s face and peaked at number 14 in the UK album chart.

Replicas saw Numan’s immersion in electronic music yield further fruit, but behind the scenes Numan was by no means the confident hitmaker implied by such strident new-wave songs. For one thing, he was well aware of the British press’ tepid reaction to this sound, later summarising: “They had been pretty harsh with the first couple of albums, saying it wasn't real music.”

"I didn't see any songs on there that were capable of being hit singles,” he told The Daily Telegraph in 2019. “There are no boxes ticked by Are 'Friends' Electric? You can't dance to it, it has no chorus, it's too long…"

Numan and Tubeway Army co-founder, bass player Paul Gardiner, continued to play together; but the rest of Tubeway army was reshuffled, replaced and expanded to constitute a backing band proper for Gary Numan as a talismanic solo artist. Momentum was at hand. Replicas hit shelves in April 1979. A matter of months later, in the September of that year, The Pleasure Principle was released. The album, a pageant of driving synth-led tracks including Metal, Films, M.E., Cars and Engineers, presented a winning coalescence of Numan’s sonic, visual and conceptual creative visions.

The album, a pageant of driving synth-led tracks including Metal, Films, M.E., Cars and Engineers, presented a winning coalescence of Numan’s creative visions

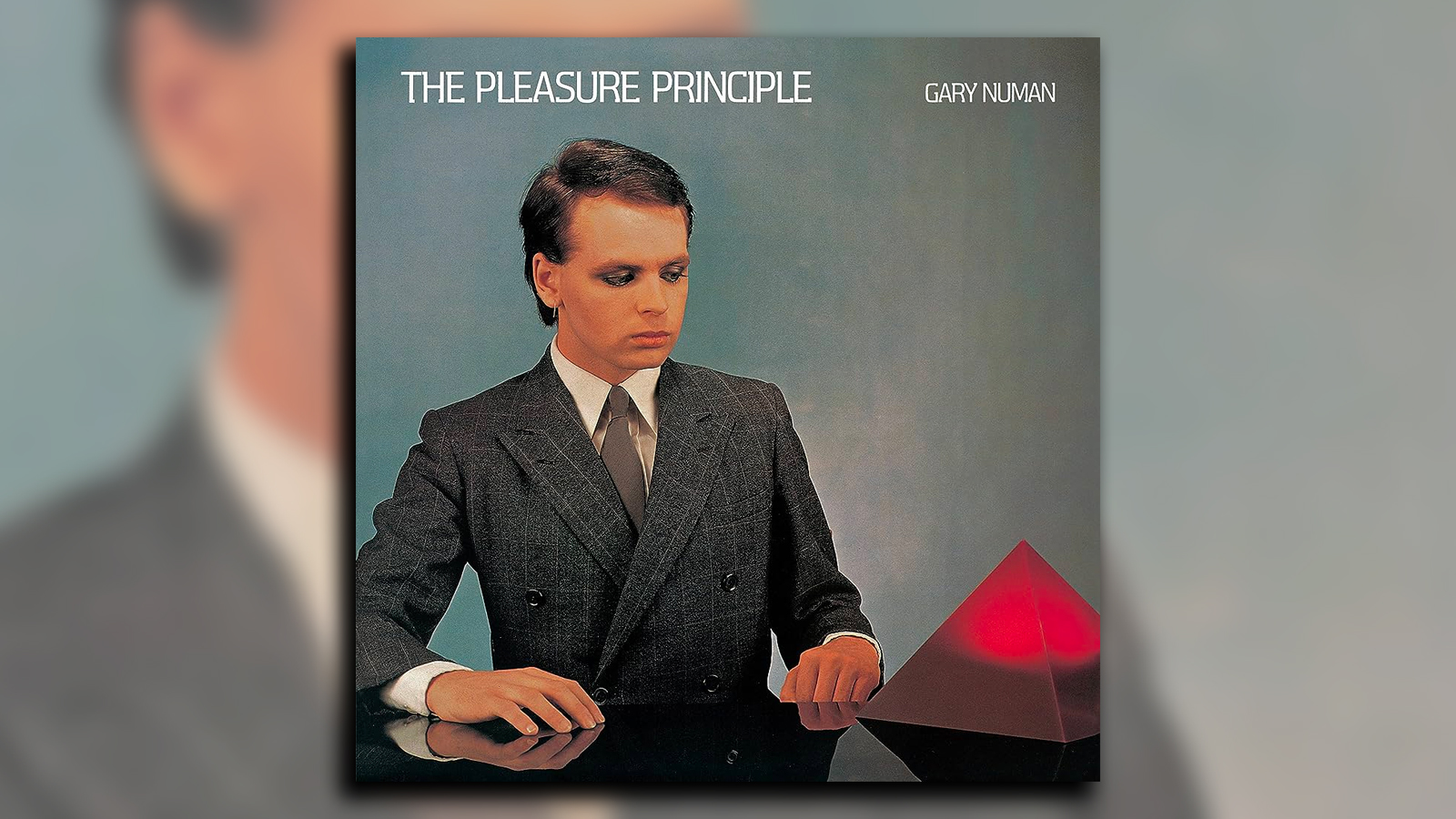

This was not least demonstrated by the album’s title and cover art: a reference to French Surrealist painter Rene Magritte’s 1937 painting The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James), the album art echoes Magritte’s painting with Numan depicted in the same dress and pose as Edward James— only this time he’s gazing down at a glowing perspex pyramid, as if it were a postmodern crystal ball revealing a dark future.

The title, The Pleasure Principle, also pertains to a Freudian theory about the driving force behind humanity’s most basic needs and urges. This contemplation of natural, primal instincts stood in stark contrast to Numan’s standoffish and robotic stage persona, simultaneously imagining a dystopian world where the relationship between technology and humanity has reached a nightmarish terminus.

Numan also explored that thematic territory in his lyrics, taking not a little inspiration from the likes of Philip K. Dick, William Burroughs and JG Ballard, whose 1973 novel Crash explored a nightmarish, fetishised union between human sexuality and car accidents. "Here in my car / I feel safest of all / I can lock all my doors / It’s the only way to live in cars", sings Numan in the album’s breakout hit. It’s grim subject matter to be sure: shopping his manuscript for the novel around, JG Ballard famously received a note from one publisher, simply reading: “This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do not publish.”

"I used to have a picture in my mind of this sad and desperately alone machine standing in a desert-like wasteland, just waiting to die"

M.E. studies a similarly dystopian vision, purportedly an acronym for Mechanical Engineering. “The song M.E. is sung from the point of view of the last living machine on Earth,” said Numan in one interview. “The people have all died, the planet is laid waste and its own power source is running down, I used to have a picture in my mind of this sad and desperately alone machine standing in a desert-like wasteland, just waiting to die.”

Beggars Banquet’s Martin Mills may have had his reservations about synthesiser-led pop in the past, but this time around he and Numan found themselves on the hunt for more synths to furnish the arsenal. “I remember going out shopping with Martin Mills at Beggars Banquet looking for other keyboards,” Numan told MusicRadar in 2021. “That’s when we found the Polymoog.” Having appeared in 1975, the Polymoog would itself come to play a key role in the making of The Pleasure Principle, not least on tracks like ‘Films’ and ‘Cars’, which made famous use of its ‘Vox Humana’ preset. Numan would eventually come to own a modest collection of two Polymoog 203a’s and six 280a’s.

Gary Numan's career in gear: "Honest to God, you could buy that and not need anything else"

The ARP Odyssey also found a warm reception in the Numan camp. “The ARP Odyssey was also phenomenal,” Numan told MusicRadar in 2021. “I veered more towards that than the Minimoog, but I’m a fan of Moog and think they’re a great company. Actually, I’m a fan of all the hardware companies. The Minimoog is arguably the most important synth ever. Not the best, but the most important. It was the machine that made electronic music accessible, and it still sounds great today.”

Numan’s band was soon touring with a total of 22 different synthesisers across five locations onstage. “They were horrifically expensive, but I owned all of them,” Numan confessed in 2016, in an interview with Reverb. "I didn’t want people showing up with their own gear and sounds, introducing an unknown quantity, and of course I couldn’t expect anyone to go out and buy a Polymoog. I’d find the right person and then supply the gear."

Synthesisers aren’t the only instruments giving The Pleasure Principle its unmistakable character, however. The album’s second single, Complex sees the appearance of Ultravox’s Billy Currie on violin, joining an arrangement whose flanging, guttural pulse-width-modulated synth sounds find themselves in the minority amongst acoustic piano, drums and bass guitar. Currie also appears on Conversation, assuming something of an acoustic foil to the track’s rich and punchy synthetic textures.

Songwriting, arrangement, synthesis, risk taking; The Pleasure Principle remains a masterclass in all of the above

Currie would remember first meeting Numan by chance while attending a Visage concert at the Drury Lane Theatre, London - a band he would soon join. “Gary invited me to play on the British tour he was about to embark on. I was happily surprised how much he was into synthesisers and how much he was into Ultravox!” He later wrote. Viola, played by Chris Payne, is also deployed to phenomenal effect on The Pleasure Principle, not least on M.E. where it enters in unassuming pizzicato to delicately harmonise the weighty central synth hook; later becoming bowed with folk-style flourishes to boot.

Rather than any kind of gimmick, acoustic stringed instruments perfectly compliment the soundstage of what is, at the end of the day, a very live-sounding album. Short, roomy reverbs and very much un-quantised drums combine with Numan’s coarse vocal delivery to retain every bit of the foundational punk ethos that underpinned his approach. Songwriting, arrangement, synthesis, risk taking; The Pleasure Principle remains a masterclass in all of the above.

"I wanted to make the point of where you could have an album that would be acceptable to the public and still be considered proper music, even if it didn't have guitars all over it." Numan reflected in 2010, in an interview with St. Louis, Missouri outlet The Riverfront Times. “I thought it was trying to prove that electronic music was valid in its own right - it just wasn't a little one-off thing, not this temporary offshoot that would all fall away given time.”

"I still think I could have done a much better job of proving the point.”