A new report by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) into the state of the River Thames has reached the surprise conclusion that it is in rude health and now home to 115 different fish species and 92 types of wildfowl.

Among the creatures now traversing its 215-mile length from the Cotswolds through the heart of London to the North Sea are seahorses, eels, seals and even sharks, including tope, starry smooth hound and spurdog, according to the study, the first “health check” the capital’s bisecting waterway has undergone in 60 years.

The most eye-catching of these visitors are perhaps the tope sharks, which can grow up to six feet long and live for half a century, and the spurdogs, which release venom from their fins as a defensive deterrent when challenged by predators.

There are also now 600 hectares of salt marsh along the length of the Thames, a crucial habitat for a range of marine wildlife and a plus in the fight against the climate crisis because of their role in capturing carbon.

While the above is great news, the report was not entirely positive, also pointing to global heating driving up the river’s water temperature by an average of 0.2C per year and to sea levels continuing to rise as they have since monitoring of the tidal Thames began in 1911, both worrying omens for the future.

And while the water quality has improved, with an increase in dissolved oxygen and a decrease in phosphorus content evident, nitrate levels remain high, which the Environment Agency blames on industrial and sewage effluent still being allowed to seep into the river.

“The Thames estuary and its associated ‘blue carbon’ habitats are critically important in our fight to mitigate climate change and build a strong and resilient future for nature and people,” said Alison Debney, ZSL conservation programme lead for wetland ecosystem recovery.

“This report has enabled us to really look at how far the Thames has come on its journey to recovery since it was declared biologically dead, and in some cases, set baselines to build from in the future.”

That claim that parts of the river were once so polluted as to be unable to support natural life dates back to 1957, when a team of scientists from the Natural History Museum in Kensington examined the Thames, their grim conclusion duly reported by Alwyne Wheeler in his article “The Fishes of the London Area” for the London Naturalist.

A century beforehand, the Thames had been notorious for its murky colour and noxious smell, with tens of thousands of Londoners regularly taken ill with cholera after washing and bathing in its waters between 1830 and 1860 and forced to continue for want of alternatives.

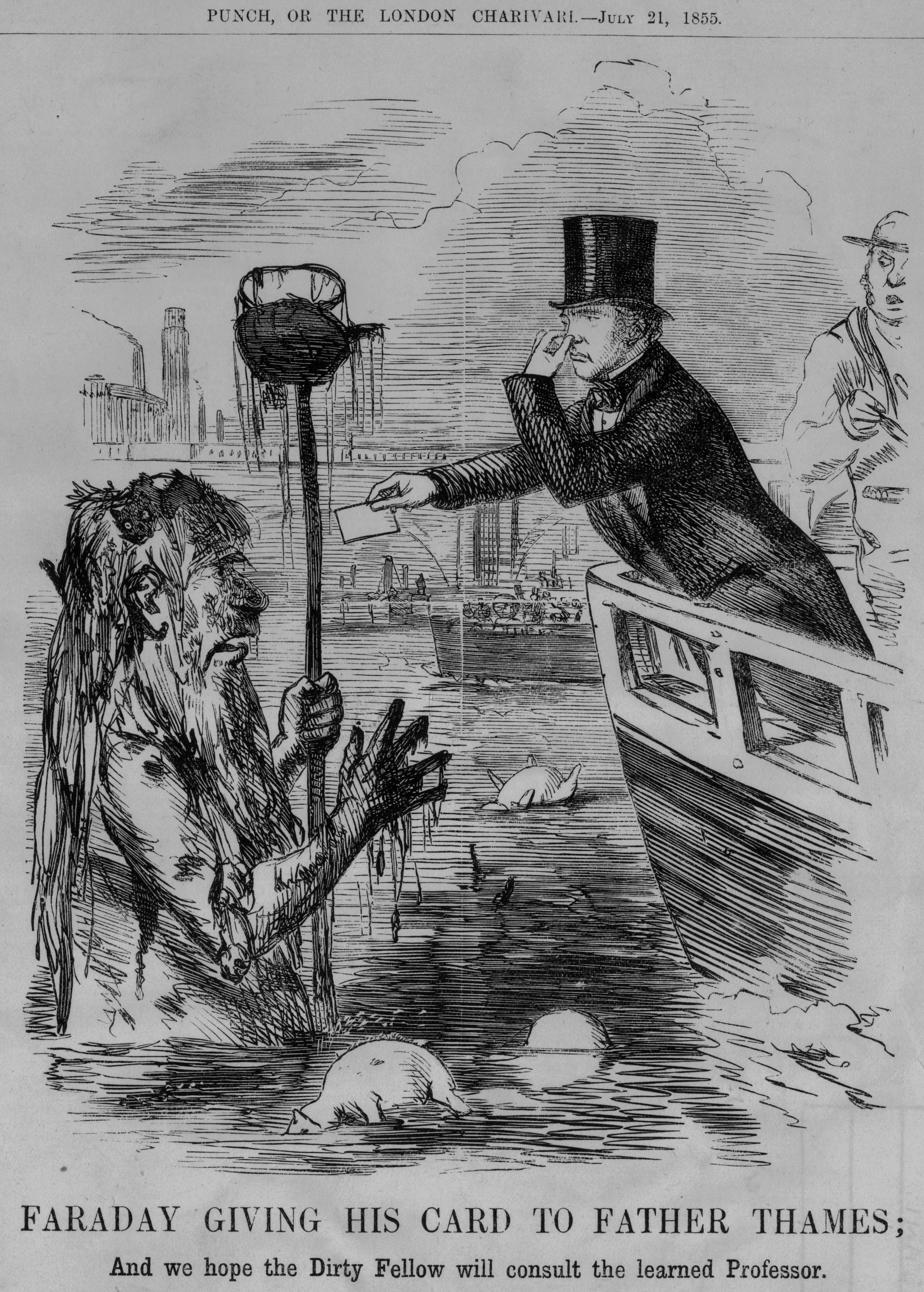

The great British scientist Michael Faraday was so disgusted by its filth after undertaking a boat trip in 1855 that he wrote a stiff letter to The Times complaining: “The whole of the river was an opaque pale brown fluid… surely the river which flows for so many miles through London ought not to be allowed to become a fermenting sewer.”

The satirical magazine Punch responded to his outrage by running a cartoon of Faraday encountering “Father Thames”, a squalid Neptune figure, and handing him a business card.

Faraday’s intervention was clearly ignored, however, because three years later, the “Big Stink” erupted, when the odour wafting from the Thames became so vile and oppressive as to drive MPs from the Houses of Parliament, causing the wheels of government to come grinding to a halt until the curtains had been soaked in chloride of lime, an episode only relieved by late summer rainfall and one that would no doubt have appealed to the sense of humour of novelist Charles Dickens, himself a former lobby journalist.

“Through the heart of the town a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river,” he wrote damningly of the Thames in Little Dorrit (1857).

Enough was enough and civil engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette was deployed by the Metropolitan Board of Works to redesign the capital’s sewage system so that effluence would be channelled eastwards beyond the city limits and no longer dumped directly into the water.

Work on his new system of subterranean pipelines and outlets was carried out between 1859 and 1875 and also saw the construction of pumping stations and the Victoria, Chelsea and Albert Embankments to ease the removal effort and bolster its banksides.

While Sir Joseph’s designs would bring an end to the cholera outbreaks, another disastrous episode occurred with the sinking of the paddle steamer the SS Princess Alice after she collided with the coal ship the Bywell Castle on 3 September 1878.

Between 600 to 700 people died in the accident and many of those not drowned subsequently passed away from illnesses associated with the water, still heavily compromised by pollution.

By the Second World War, treatment plants were in common use to clean the waters of the Thames, but their destruction by Luftwaffe bombers during the Blitz caused noxious waste to be spilled back into the river and kill off much of its fish and marine plants, a major ecological setback for the capital leading to the nadir identified by the Natural History Museum team in 1957, a period when only eels were thought to thrive from Fulham downriver to Tilbury.

Subsequent reinvestment in sewage treatment infrastructure and tighter regulation on industrial dumping since the 1960s, coupled with the waterway’s reduced role in cargo transport in more recent decades and greater stocktaking of the river’s fauna and flora by men like Alywynne Wheeler, has seen the Thames gradually clear and recover its vigour, the recovery resulting in its becoming a happy home for venomous sharks in 2021.

Although that could prove to be a mixed blessing...