Of the destinations across England’s tour of South Africa, Port Elizabeth is perhaps the most one-horse of cities. And, of the places you’ll go across four Tests, three ODIs and three T20is, the most authentic.

What you see of it in a week of following cricket, where your days are occupied and your nights limited yet loose, is confined to a coastal strip that feels like it should be so much more. Barney’s, Beer Shack, White Tiger are three establishments that saw the most trade on a road running alongside the coast where walking is actively discouraged.

That advice, as bleak as it may be, is one of the reasons Port Elizabeth gives travelling Englishmen and women the most accurate, bitter taste of South Africa.

The qualities of it are not really qualities at all. Organised crime and drug abuse, particularly heroin, has been on the increase here over the previous decade. In 2016 a march took place in Shaudeville to protest against gangsters in the area who had been working their ways into schools to further protection rackets and even sell drugs on the premises.

Various England fans were robbed at knifepoint down Beach Road either between establishments or right outside their hotels in fading daylight. And as the WhatsApps came through of various incidents – three in the space of 24 hours, five in the space of 48 – the underlying sense was the warnings to stick together and not meaner about at night were stuck to rigidly for the first three weeks and then let slip where and when it was needed most. With the Pound in town, there is usually a spike in these incidences as the reward of the crime increases while the risk remains the same.

But the core of Port Elizabeth is quintessentially South Africa. This is a proud nation that tries to avert your eyes from its rough-and-ready bits while drawing character from them, and this city does the same. The locals are straight-talking, happy to call you a fool for sticking to the strip when "Central" is just a 10-minute cab away. The advice and experiences here are the realest you will get if you’re not from these parts and willing to stick around and listen.

That's not the case in Cape Town where, like New York, Melbourne or London, the city is tailor-made for you to step onto the carousel and pretend you’re part of the hustle. But in Port Elizabeth, like the rest of the country, the hustle happens around you.

Just as England’s cricketers found when they stepped into this tour before Christmas, battles for governance may be parked for the cricket to save face, but the toughest conversation never stops. And that conversation, as ever, is around transformation.

“You know he only averages 30 since then?” It was not the first time this number – Faf du Plessis’ average since the start of 2018 – was put in front of me. It had done the rounds on Twitter, retweeted online and then orally across various mediums. But it was the first time the subject was broached in the back of a cab as we made our way to the pre-match press conferences a day out from the third Test at St George’s Park.

This is not the kind of sporting nation where they gun for the captain. But du Plessis was in the sights of many prominent black Africans – and, subsequently, black Africa – for his comments prior to the first Test.

When quizzed on the absence of Temba Bavuma, he sighted the opportunities of 39 caps and an average of 31. More clumsily – English is not du Plessis’ first language – he prefaced this with a jarring soundbite: “We don’t see colour and I think it is important that people understand that opportunity is very important – an opportunity for everyone.”

Faf might not see colour, but they see his numbers.

The origin of the question was rooted in a foreshadowing that Cricket South Africa’s own transformation targets would not be met in the series. A benchmark of selecting an average of six non-white players, including two black Africans, in the national team across 12 months, as per the policy introduced in 2013.

Four non-white players – Zubayr Hamza, Vernon Philander, Keshav Maharaj and Kagiso Rabada – were picked in the first three Tests. By the fourth at The Wanderers, Maharaj and Hamza were dropped and Rabada unselectable through suspension. In came Bavuma to hold the fort as the sole black representative.

Bavuma has unwittingly become the modern poster-boy for transformation. He is not simply a cricketer from a township – Langa, just outside of Cape Town – but South Africa’s first black Test batsman and, against England in 2016, their first black centurion, and still their only.

But from being prepped to be lauded as a victor, he has had more turns as the victim. Though neither sat well with him, age has given him a perspective he has been able to use for the highs and lows. Take, for example, his words after his 98 against England in the opening victory of this ODI series.

“The awkwardness and uncomfortability from my side is when you are thrown into talks of transformation.

“Yes, I am black, that’s my skin. But I play cricket because I love it. I’d like to think the reason I am in the team is because of performances I have put forward in my franchise side, and also for the national team, whenever I have been able to. The discomfort was there, having to navigate myself around all those types of talks. Players get dropped, I am not the last guy to get dropped. That’s something we’ve come to accept.”

The clarity of those words is reflective of the current discourse going on among the country’s coming generations. There is a wokeness like never before brought about through those who demand answers for the societal flaws in place well before they became sentient.

A country once reluctant to confront its own history of apartheid is now doing so on a daily basis. Conversations around race are raw, painfully honest yet refreshing. So much so, that they can be jarring to outsiders.

This was evident with those of us in the English touring party who shirked at the idea of having to type the words “black” and “coloured” into our previews. The quest for more palatable synonyms is in its own way a coping mechanism.

Invariably, the most productive considerations stem from white privilege.

In “Will South Africa be okay?”, a book by political journalist Jan-Jan Joubert, the chapter entitled “What is the role of whites in South Africa?” calls for whites “to reach out beyond our own enclaves and cheerfully, amiably and reflectively put shoulder to the wheel together with every other South African to best enjoy and help build up our country”. He supplements this thought with a valuable caveat lost among some of his peers: “There are no guarantees of reciprocity, and that is also not what it’s about – decency is its own reward.”

While in conversation with Indian newspapers The Hindu, Deccan Chronicle and The New Indian Express, Proteas legend Jonty Rhodes turned the conversation onto himself: “I certainly benefited from the fact that I wasn’t really competing with 50% of the population.

“You talk about white privilege and it raises a lot of heat and debate on social media but it is the case. I’m very aware of that. My cricketing statistics as a player were very average when I was selected.”

There is, of course, blowback when a group must ask tough questions of themselves. There remains part of South Africa, not simply just South Africans, who regard its whiteness as its best trait. Derogatory terms like “coon” occasionally sting your ears when in certain company.

The worst element of these objections are felt in cricket, more so than in rugby which is also regarded as a predominantly white sport.

Last year’s World Cup success guided by Siya Kolisi, himself a township boy from Zwide outside Port Elizabeth, has built on the inspiration of him and other black African Springboks. But the bonus the sport has over cricket is ease. From grassroots to the green shirt, the fundamental of picking up the ball and running straight remains. Perhaps even kick it 20 or 30 times.

Despite CSA’s network of hubs in harder-to-reach places and independent foundations that look to improve access to the game by building new or rejuvenating old training facilities in impoverished areas, the public school system continues to prop up South African cricket.

It is why, even with the drain through retirements and players turning their back on international cricket to make a better living in England, there is a steadfast belief the talent will keep coming.

There are around 35 high schools that consistently pump out those who leave at 18 ready for the rigours of provincial and professional cricket. The quality of facilities, coaching and simply the stock placed in the game supersedes what other schools could offer as a hobby let alone a a priority.

Even those vaunted players of colour are not quite original products of their environment. Makhaya Ntini, the country’s first black African Test player, went to Dale College. Hashim Amla went to Durban High. Kagiso Rabada is a former St Stithians Boy. Lungu Ngidi honed his cricketing education at Hilton College. And Bavuma, pitched as the boy whose front elbow was pushed highest at Soweto Cricket Club, is regarded as notable alumni at St David’s Marist, Sandton.

Some see the antidote to this disparity in bursaries to those within townships with clear talent. The most worthwhile idea – and, sadly, most far-fetched – is to improve those institutions within these areas themselves. But how do you undo centuries of deprivation and neglect, the sort that existed well before apartheid?

It is a quandary that rattles many heads, particularly Dr Ali Bacher's.

“If there’s a good young talented cricketer and he’s in the townships and he stays in the township unless he’s got Brian Lara’s genes, he’s not going to make it,” he tells the Independent.

Bacher has been many things to cricket in South Africa. He played 12 Tests and captained his country, but his name, for better and worse, was made as an administrator for CSA’s former iteration, the United Cricket Board of South Africa.

It was Bacher who organised the rebel tours of the 1980s when South Africa was a no-go sporting state during apartheid. Though he was able to reassess and take the team through readmission, there remains deep regret.

“I’ve acknowledged for decades that I was heavily involved in those tours,” he says. “It’s not something to get away from.

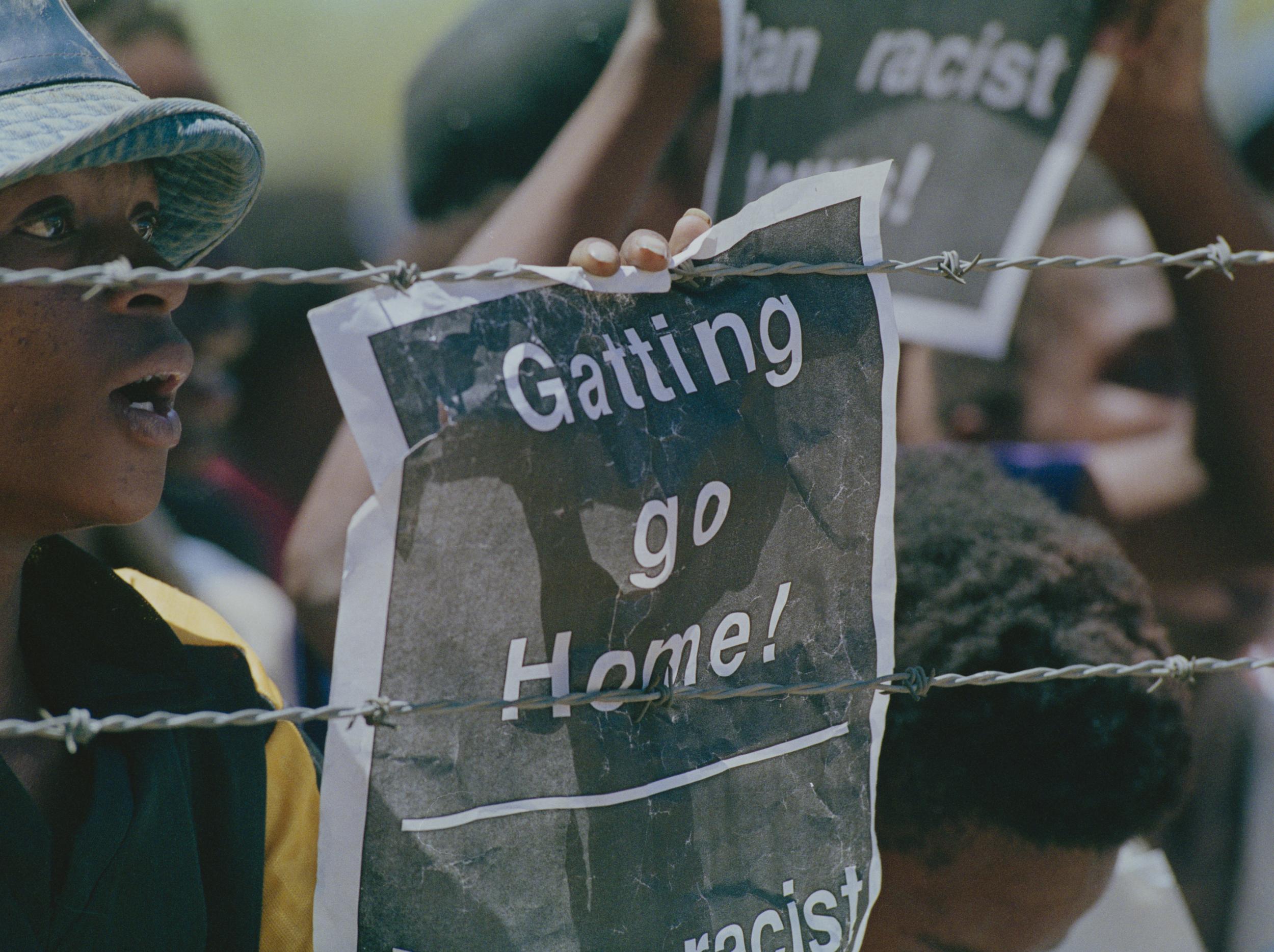

“But when Mike Gatting’s team came to South Africa and I saw the anger – I mean, it was hatred, really – by the majority of people, I knew in that moment.”

Gatting’s tour in 1990 was the seventh and last of the rebel tours, met, as Bacher alludes to, with a vitriol unseen before which shakes him to this day. Players were given “honorary white status” and, for their first of those seven times, their palms lined with silver by the apartheid government rather than sponsors.

The tour was shortened as threats of violence, even murder, intensified. Such was the gross mistiming that when Nelson Mandela was released from prison on 11 February, some of the English journalists covering the tour were reassigned to report on his release.

“Maybe I was naive,” says Bacher. “But if I had known it would elicit that type of reaction, I would have thought twice.”

Bacher, now 77, might be the best example of the moral struggle among modern South Africans. His stock as a man of the game, and indeed a man outright, varies wildly across each cross-section.

To some, including modern white South Africans, the rebel tours are a blemish he will never wash away. The about-turn from 1991 onwards, too little too late.

For others of an older generation, he is remembered, if not revered, as the one who did what he could to bring cricket home.

But it is telling that even for Bacher, he’s not really sure which suits him.

“Maybe what I did showed that you can’t have international cricket without having the majority of South Africa behind it? Or perhaps history will show it was a necessary tour for the future well-being of South African sport? I have these conversations with myself and my friends. I never know which.”

There, ultimately, might be the unshakeable feeling you get from South Africa, both inside and well beyond its cricket. This is a braver and more open country than ever before. And yet, after the false dawn of the Rainbow Nation there remains an awkward uncertainty as to where they go now and what happens next.