Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

I have a question about ice on the Moon. How is this possible? – Olaf, age 9, Hillsborough, North Carolina

We’re lucky to live on a water world. More than 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water.

Earth is about 94 million miles from the Sun. That’s within the Goldilocks zone: the place in our solar system where a planet has just the right temperature for water to exist in oceans and rivers as a liquid and as ice in the north and south poles.

Earth also has an atmosphere more than 6,000 miles (9,650 kilometers) thick that’s filled with oxygen for us to breathe. This atmosphere, along with a huge magnet in the center of the Earth, helps protect us from the Sun’s harmful radiation, mostly solar wind and cosmic rays.

But the Moon hardly looks like a water world, or even a place with a few puddles. It has a worn-out internal magnet and an atmosphere so weak it’s virtually a vacuum. There are no clouds or rain or snow, just a sky that’s only the blackness of space, with a surface baked by the Sun. The Moon’s temperature reaches 273 degrees Fahrenheit (134 Celsius) by day and goes as low as -243 F (-153 C) at night.

But as scientists who study space and work to develop technologies that look for the water, we can definitively say: Yes, the Moon has water.

The discovery

For a long time, astronomers and other scientists thought Moon water was unlikely. After all, the Apollo astronauts brought back many rock samples from the Moon, and all were dry, with no detectable water.

But visits by recent spacecraft showed that some water is there. In 2009, NASA smashed a spacecraft – the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS – into the Moon’s surface, inside Cabeus crater. When that happened, water ice was ejected.

This confirmed to scientists that water ice was in the bottom of the craters. But determining how much water is there will be difficult. The 10,000 or so Moon craters are essentially big holes, with areas so shaded the Sun never shines inside. These places are really cold, well under -300 F (-184 C). Once these frozen water molecules get stuck in the craters, they pretty much stay forever, unless some heat or energy dislodges them. They are unlikely to naturally evaporate or sublimate as vapor – it’s just too cold in there.

But that doesn’t mean water is stored only in craters. In 2023, scientists using SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, looked for water on the Moon’s surface in areas that were not as cold as the craters. And they found it – not on top of the soil, but probably inside the soil grains.

No one knows yet how much water the Moon has or how deep it goes. But one thing is certain: There’s much more than scientists first thought.

Comets and volcanoes

How did the Moon get its water? No one is certain yet, but there are some theories.

Eons ago, comets – which are basically frozen, dirty snowballs – crashed into Earth, leaving their comet water. That’s one of the ways Earth developed its oceans; perhaps that’s how the Moon got some of its water too.

Other scientists think ancient volcanoes on the Moon released water vapor when they erupted billions of years ago. Eventually, that vapor descended to the surface as frost. Over time, layers of that frost accumulated, particularly at the poles; much of it may have found its way inside lunar craters as ice.

Drinking water for astronauts

Water is heavy. Transporting it to the Moon by spacecraft would be costly. So it makes more sense for astronauts to figure out a way to use the water already on the Moon.

But Moon water is not drinkable as is; it would have small pieces of the lunar soil and possibly other molecules mixed with it. Astronauts living in Moon colonies would need to purify any water they collected. This is a tricky process that would require considerable effort and resources.

There is a plan to drill for the water and look for it, the way people hunted for underground gold during the 19th century gold rush. The analogy is not a bad one – water on the Moon might eventually be more valuable than gold on Earth.

And not just for drinking. Water, of course, is two parts hydrogen, one part oxygen; it can be split. This is a win-win: Astronauts can use the hydrogen for rocket fuel and the oxygen for breathable air. Using the Sun as a power source, the water splitting is probably doable.

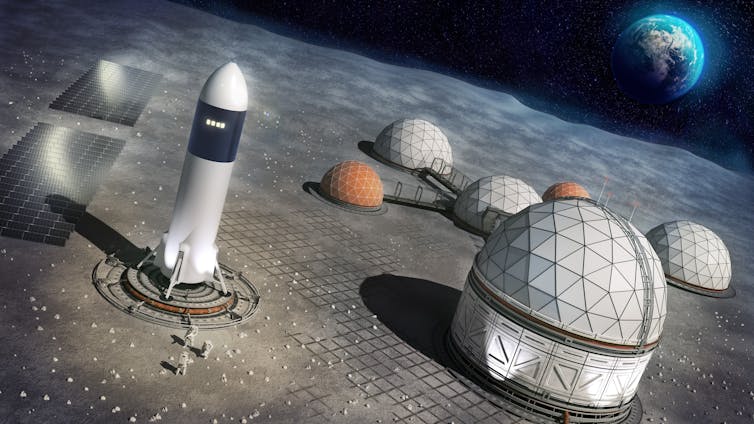

Returning to the Moon and establishing a permanent base are enormous commitments requiring decades of work, billions of dollars, the cooperation of many nations, and many new technologies yet to be developed. But as the world enters this dramatic new chapter of space exploration, pioneers run the risk of destroying or polluting a unique environment that has been in existence for billions of years – and many scientists feel a deep obligation not to repeat the painful lesson we’re now learning here on Earth.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Thomas Orlando receives funding from NASA and DOE.

Frances Rivera-Hernández and Glenn Lightsey do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.