The West Coast of Canada is known for its wet autumn weather, but the storm that British Columbia’s Fraser Valley experienced over the weekend was one for the record books.

A weather system called an “atmospheric river” flowed across the southwest corner of the province and, over a period of two days, brought strong winds and near-record amounts of rain, which caused widespread flooding and landslides. So far, one person has died.

Hope, Merritt and Princeton, which were particularly hard hit, received 100-200 millimetres (or more) of rainfall. And all of the highways connecting Vancouver to the rest of the province were closed due to washouts and landslides, isolating the city from the rest of Canada, at least by road, with significant economic impacts.

What is an atmospheric river?

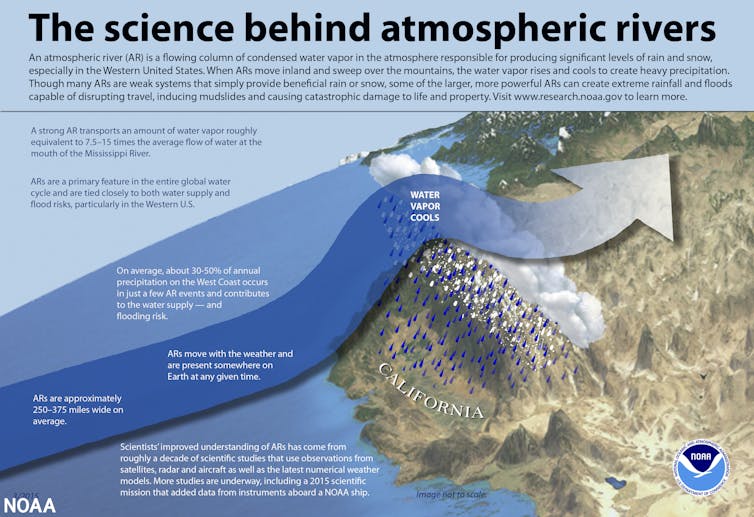

An atmospheric river is a band of warm, moisture-laden air many hundreds of kilometres long and hundreds of kilometres wide that borders a large cyclonic low-pressure system.

The term has been applied to bands of moisture-associated weather systems that move inland from the Pacific Ocean. An atmospheric river can reach the coast anywhere between southeast Alaska and Northern California.

Because of the large amount of moisture conveyed in these weather systems, the term has become a metaphor for a terrestrial river. However, atmospheric rivers are not carried in a channel like a real river and can dump prodigious amounts of rain over large areas.

Was it a record-breaking rainfall?

The weekend storm was noteworthy for both its duration and its intensity. It rained continuously over much of the storm track for more than 24 hours and the rate was higher than normal autumn rains.

In both cases, rapid runoff exceeded the carrying capacity of streams and rivers, causing them to spill out onto floodplains. In addition, flat areas like the Sumas Prairie area between Abbotsford and Chilliwack had already been saturated with October and early November rainfall, were unable to drain away the water and were consequently flooded.

Furthermore, snow at high elevations melted under the warm rainfall, exacerbating the flooding. Rainfall on Nov. 14 set records for many places in the region. For example, Abbotsford recorded 100 millimetres of rain that day, exceeding the previous record of 49 millimetres set in 1998. Hope had 174 millimetres, five times the amount in the record year of 2018.

Did summer wildfires make the situation worse?

B.C. had its second worst wildfire summer season in 2021, with more than 1,600 fires charring nearly 8,700 square kilometers, mainly in the southern part of the province. Only 2017 saw more forest lands burned.

Soils in forested landscapes are hydrophobic after severe fires — they repel water. Super-heated air during a wildfire disperses waxy compounds found in the uppermost forest litter layer. The compounds coat mineral grains in the underlying soil, making it hydrophobic. The water-repelling layer is typically found at or a few centimetres below the ground surface and is commonly covered by a layer of burned soil or ash.

Many areas burned during the 2021 wildfires, such as around Merritt, were deluged by rain the weekend of Nov. 13. It is possible that runoff from these burned grounds was greater and more rapid because of the hydrophobicity of the soil.

Is this related to climate change?

Scientists are generally reluctant to attribute single extreme weather events to climate change, but the exceptional events of recent years are shifting opinion.

Examples of such exceptional events include flooding in western Germany and eastern Belgium and in Henan Province China, both in July 2021; extreme heat and wildfires in Siberia in 2020 and 2021; and the “heat dome” over western North America at the end of June 2021.

These events are so far “off scale” in comparison to past historic extreme events that climate modellers assert that they would not have happened or would not have been as severe were it not for climate change.

Such events are consistent with predictions made by atmospheric scientists that weather extremes will become more frequent and more severe as Earth’s climate continues to warm.

John J Clague does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.