No one ever thought to listen to what women had to say.

As cases were argued in courts across the country, the fight for legal abortion was always heard from the perspective of the male doctors in the room and their right to practice medicine.

The women forced to go through an unwanted or unsafe pregnancy were never even part of the conversation.

That all changed in 1970 when attorney Nancy Stearns brought a legal case in New York that finally gave women impacted by abortion restrictions a voice in the courts for the first time.

“It had never been done before,” Ms Stearns tells The Independent.

“Up until our case, abortion laws had always been challenged and the courts had formulated their opinions in the context of the criminal prosecution of doctors or the people referring women for procedures.

“It was always seen through the eyes of the doctor and the impact on women was barely even discussed.

“We wanted to bring women into the court to say ‘this law impacts me and this law impacts other women’. So we devoted the case just to the impact on women.”

And so, in the case of Abramowicz v Lefkowitz, Ms Stearns and her fellow attorney and activist Florynce Kennedy brought the first legal challenge to abortion laws in American history where women were the plaintiffs.

For the first time, the legal challenge was based on a woman’s right to abortion and not a doctor’s right to practice medicine.

And for the first time, women had a voice in the fight for abortion access in the US courts.

The lawyers didn’t want to just give one woman a voice either.

“We wanted to get as many women as we could to come in and say this is hurting me. That either ‘I’ve had to get an illegal abortion in the past’ or ‘I had to go through a whole pregnancy and give my child up for adoption’ or ‘I lost my job because of being pregnant’: all those things that restrict women,” she says.

It was a strategy borrowed from the civil rights movement with Ms Stearns having worked at the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee – the student-led arm of the civil rights movement founded by John Lewis – before she went to law school.

“And there were a couple of reasons for doing this,” explains Ms Stearns.

“One – so that no woman would carry the fight for all women just on her shoulders.

“And two – so that women together could say to the court ‘there’s lots of us out here already impacted by restrictive abortion laws and we will be affected again’.”

In total, more than 300 women joined the same case challenging a New York law that banned abortion with the only exception being when the mother’s life was at risk.

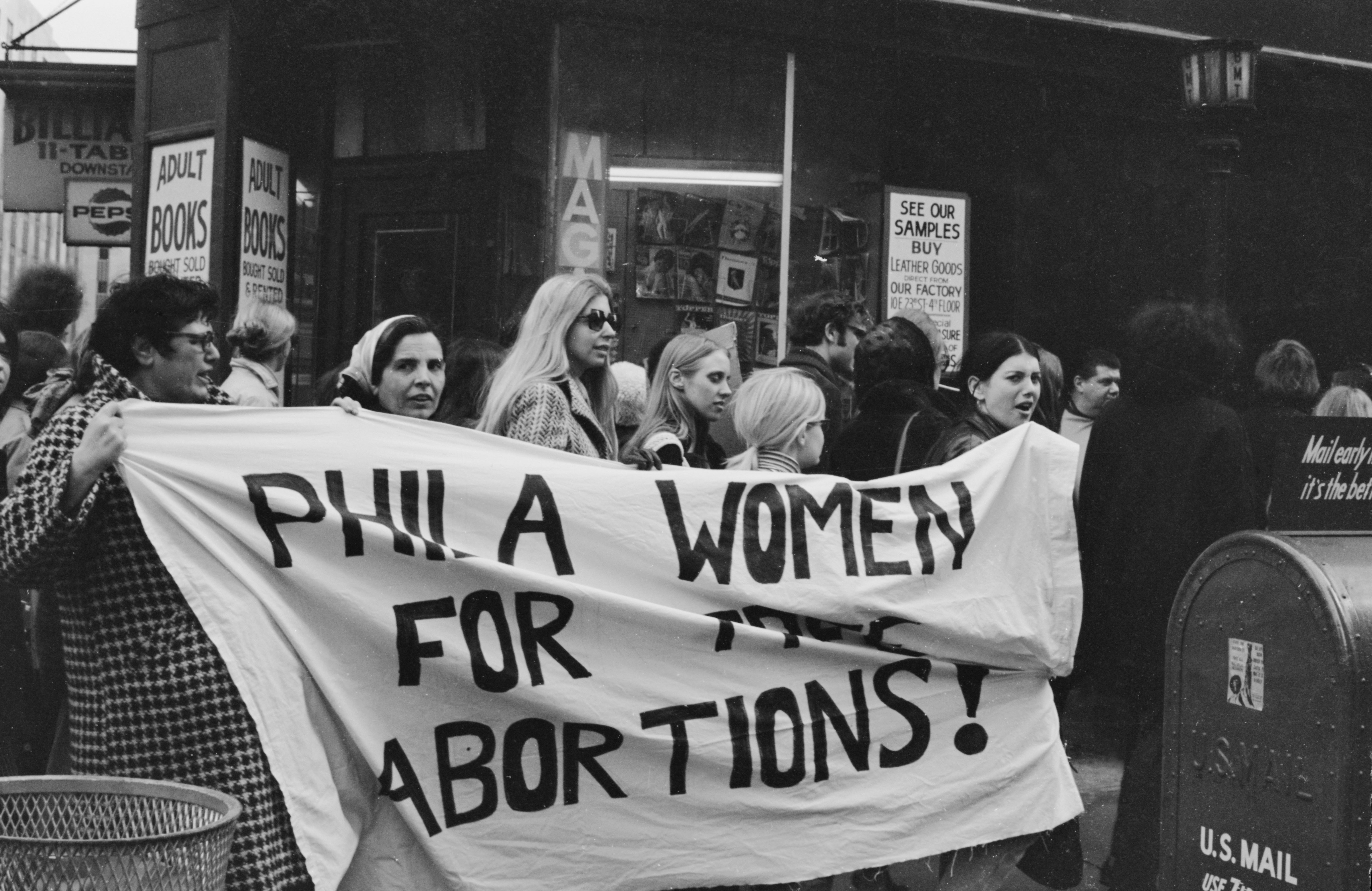

In January of 1970, many of those women packed into a courtroom in Manhattan and shared their personal stories in testimony unlike anything ever before heard in a court of law.

Silenced again

But, five decades on, the voices of women are being ignored by the courts once more.

On 24 June, the US Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to abortion and pushed abortion access back in time to the early 1970s.

In ruling on the case of Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the six conservative justices sided with a Mississippi law that outlaws abortion at 15 weeks of pregnancy.

In the decision, they also overturned Roe v Wade – the landmark decision which ruled that Americans had a constitutional right to abortion and which came just three years after Ms Stearns brought the legal challenge in New York.

Now, the power over whether a woman can make decisions about her own body lies with the lawmakers in individual states, with around 36 million women estimated to soon be living in places where they no longer have access to the medical procedure.

Despite the Supreme Court’s decision to shatter 50 years of precedent around abortion access, Ms Stearns insists that women will not “be silenced” by the ruling.

“Women are not going to be silenced,” says Ms Stearns.

“Now that they have a voice women will not stop fighting.”

She adds: “But many women are going to be harmed and some are going to die [because of the Supreme Court’s decision].”

While it was Roe v Wade that led to women across America having the fundamental right to abortion access, Ms Stearns’ case in New York actually came first.

And – as well as being the first case to challenge abortion laws on behalf of women – it was also fought on a never-before-seen argument that access to legal abortion is fundamental to women’s equality.

Equal protection challenge

In Abramowicz v Lefkowitz, the attorneys were challenging restrictive abortion laws based on a women’s constitutional right to equal protection and liberty.

But the case wound up never reaching the Supreme Court.

In April 1970 – just three months after the crowd of female plaintiffs flocked to the Manhattan court – New York lawmakers legalised abortion in the state up to 24 weeks of pregnancy.

With abortion now legal, the case was no longer relevant and was dismissed.

Ms Stearns then turned her attention to the fight for abortion in other states including Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Jersey, using the legal challenge of a woman’s constitutional right to equality and the activist-style strategy of bringing multiple women on board as plaintiffs as a prototype for the cases.

In Connecticut, more than 800 women joined the case of Abele v Markle, challenging the state’s abortion law which only allowed the procedure when the life of the mother was in danger.

The attorney also took on the case of Shirley Wheeler who was the first woman in the US to be convicted for having an abortion in Florida in 1971.

It was at the same time that Abele v Markle was making its way through the courts that the Supreme Court heard the case of Roe v Wade.

In that case, the attorneys challenged the abortion ban in the state of Texas in a different way.

For one, the case was based on one individual woman – Norma McCorvey, an unmarried 22-year-old woman who had fallen pregnant with her third child and was known under the pseudonym Jane Roe.

But – perhaps more significantly – the abortion ban was challenged on the constitutional right to privacy through the 14th amendment.

“We were arguing equal protection and the right to liberty which you also get through the 14th amendment,” says Ms Stearns of her cases.

“But we argued a lot of different rights. We also argued [under the eighth amendment] that it was a cruel and unusual punishment to make women go through nine months of pregnancy that they didn’t want to.”

They also argued that banning abortion was unconstituional under the first amendment which says that church and state must be separate and which prohibits the federal government from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion”.

That argument was that forcing women to carry a pregnancy was based on a religious belief that a foetus is a human being from conception.

Roe was also partly argued on liberty – and Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion on Dobbs v Jackson focused heavily on ruling that the right to abortion does not fall within that constitutional right.

Ms Stearns explains that the right to privacy and the right to liberty are tied closely together and, that back when Roe passed, it was perhaps an easier argument than focusing on the right to equal protection.

An easier argument

Roe came just years after the case of Griswold v Connecticut, where the Supreme Court ruled that married couples were free to buy and use contraception under the right to privacy.

By contrast, no case had ever been won under equal protection based on discrimination on the grounds of sex.

In fact, one year after Roe passed, the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination against a woman because she was pregnant was not protected by the right to equal protection on the basis of gender in Geduldig v Aiello.

“The equal protection argument was a hard argument to make to judges at the time because they couldn’t understand that reproductive life is central to a woman’s life and that if they don’t have control over it they will never be equal in society,” says Ms Stearns.

“They couldn’t understand that because at that time all the justices in the Supreme Court were men and almost all the judges in the lower courts were also men. So none of the courts got it.”

However, questions have been raised around whether the US could be in a different position on abortion rights now if the precedent-setting case had been argued differently.

When asked if she thinks the right to abortion access would have still been overturned if it was her case and the equal protection argument that landed on the desk of the Supreme Court first, Ms Stearns says she “do[es]n’t have the answer” .

“The reason I don’t know is because Roe was partially privacy and partially liberty,” she says.

“And if these judges don’t believe there is liberty they could also say that on equal protection too.”

‘A sad place to be’

But what she is almost certain of is that there is no point in trying to challenge abortion bans in the Supreme Court based on the right to equality now.

“Not in this court,” she says.

“The court just dismissed the rights of half the population because of their own personal beliefs. What underlies this is [the justices’] religious beliefs and it’s not so important to [the justices] that women’s rights are harmed. They don’t see this as women’s rights.”

She adds: “And that’s a very sad place to be. But that’s where we are unfortunately.”

The Supreme Court has now become a group of people ruling on their own personal views and religious beliefs rather than ruling on the law, she says – something that is a direct violation of the oaths they took when they became judges.

“It runs counter to being a judge,” she says.

“Judges aren’t supposed to be making decisions based on their personal morals and views.”

She adds: “You’ve got judges who I think have religious beliefs that the foetus is a human being from conception and they’re not going to budge.”

She points to the dissent from Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan which questioned the majority’s reasoning in last month’s ruling.

“The Court reverses course today for one reason and one reason only: because the composition of this Court has changed. Stare decisis, this Court has often said, “contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process” by ensuring that decisions are “founded in the law rather than in the proclivities of individuals.” Today, the proclivities of individuals rule. The Court departs from its obligation to faithfully and impartially apply the law. We dissent,” it reads.

Echoing the dissent, Ms Stearns says that “the Supreme Court is now a political institution that depends on the personal opinions of the people on it.”

And as long as the court make-up stays as it is, Ms Stearns isn’t sure how lawyers will be able to successfully challenge abortion bans before the Supreme Court today.

“I’m not sure I’d see a point to it as long as these judges are controlling it,” she says.

Though she doubts it would make any difference to a Supreme Court ruling, she says that raising the religion argument in the court would at least expose to the American people that the justices are ruling on their personal beliefs rather than the law they took an oath to apply.

“If the religion argument was raised now in the Supreme Court they’d say it’s about morals not religion but I think it’s worth confronting these people with it,” she says.

“Basically say ‘this is a religious question and I know you’re not going to admit it but I’m putting it before you’.”

She adds: “This is now a political issue and a political court.

“This is a political fight and we need to figure out how to fight it.”