In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

Insects have always been intimately connected with agriculture. Pest insects can cause tremendous damage, while helpful insects like pollinators and predators provide free services. The relatively young field of agricultural entomology uses knowledge of insect ecology and behaviour to help farmers protect their crops.

One of the most influential agricultural entomologists in history was an insatiably curious and fiercely independent woman named Eleanor Anne Ormerod. Although she lacked formal scientific training, Ormerod would eventually be hailed as the “Protectress of British Agriculture”.

Eleanor was born in 1828 to a wealthy British family. She did not attend school and was instead tutored by her mother on subjects thought to increase her marriageability: languages, drawing and music.

Like most modern entomologists, Eleanor’s interest in insects started when she was a child. In her autobiography, she tells of how she once spent hours observing water bugs swimming in a small glass. When one of the insects was injured, it was immediately consumed by the others.

Shocked, Eleanor hurried to tell her father about what she had seen but he dismissed her observations. Eleanor writes that while her family tolerated her interest in science, they were not particularly supportive of it.

Securing an advantageous marriage was supposed to be the primary goal of wealthy young women in Eleanor’s day. But her father was reclusive and disliked socialising; as a result, the family didn’t have the social connections needed to secure marriages for the children. Of Ormerod’s three sisters, none would marry.

The Ormerod daughters were relatively fortunate; their father gave them enough money to live comfortably for the rest of their lives. Their status as wealthy unmarried women gave them the freedom to pursue their interests free from domestic responsibilities and the demands of husbands or fathers. For Eleanor, this meant time to indulge her scientific curiosity.

Foaming at the mouth

Ormerod’s first scientific publication was about the poisonous secretions of the Triton newt. After testing the poison’s effects on an unfortunate cat, she decided to test it on herself by putting the tail of a live newt into her mouth. The unpleasant effects – which included foaming at the mouth, oral convulsions and a headache – were all carefully described in her paper.

Omerod’s first foray into agricultural entomology came in 1868, when the Royal Horticultural Society asked for help creating a collection of insects both helpful and harmful to British agriculture. She enthusiastically answered the call and spent the next decade collecting and identifying insects on the society’s behalf.

In the process, she developed specialist skills in insect identification, behaviour and ecology.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Flos Greig, Australia’s first female lawyer and early innovator

During her insect-collecting trips, Ormerod spoke with farmers who told her of their many and varied pest problems. She realised that farmers were in need of science-based advice for protecting their crops from insect pests.

Yet most professional entomologists of the time were focused on the collection and classification of insects; they had little interest in applying their knowledge to agriculture. Ormerod decided to fill the vacant role of “agricultural entomologist” herself.

In 1877, Ormerod self-published the first of what was to become a series of 22 annual reports that provided guidelines for the control of insect pests in a variety of crops. Each pest was described in detail including particulars of its appearance, behaviour and ecology. The reports were aimed at farmers and were written in an easy-to-read style.

An early form of crowdsourcing

Ormerod wanted to create a resource that would help farmers all over Britain. She quickly realised this task would require more information than she could possibly collect on her own. So Ormerod turned to an early version of crowdsourcing to obtain data.

She circulated questionnaires throughout the countryside asking farmers about the pests they observed, and the pest control remedies they had tried.

Whenever possible, she conducted experiments or made observations to confirm information she received from her network of farmers. Each of her reports combined her own work with that of the farmers and labourers she corresponded with. The resulting reports cemented Ormerod’s reputation.

Ormerod was invited to give lectures at colleges and institutes throughout Britain. She lent her expertise to pest problems in places as far afield as New Zealand, the West Indies and South Africa.

In recognition of her service, she was awarded an honorary law degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1900 - the first women in the university’s history to receive the honour. Such was her fame that acclaimed author Virginia Woolf later wrote a fictionalised account of Ormerod’s life called Miss Ormerod.

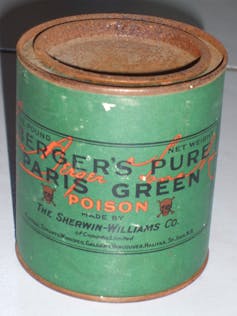

While she undoubtedly contributed to the rise of agricultural entomology as a scientific field, Ormerod’s legacy is complicated by her vocal support of a dangerous insecticide known as Paris Green. Paris Green was an arsenic-derived compound initially used as a paint (hence the name).

Although Paris Green was used extensively in North America, it was relatively unheard of in Britain. Ormerod made it her mission to introduce this new advance to British farmers. So strongly did she believe in its crop-saving power, she joked about wanting the words, “She brought Paris Green to Britain,” engraved on her tombstone.

Unfortunately, Paris Green is a “broad spectrum” insecticide that kills most insects, including pollinators and predators. The loss of predators in the crop ecosystem gives free rein to pests, creating a vicious cycle of dependence on chemical insecticides.

Paris Green also has serious human health impacts, some of which were recognised even in Ormerod’s day. The fact that arsenic was a common ingredient in all manner of products - including medicines - may partly explain why Ormerod seems to have underestimated the danger of Paris Green to human and environmental health.

Ormerod’s steadfast promotion of Paris Green seems naïve in retrospect. But the late 1800’s was a time of tremendous optimism about the power of science to solve the world’s problems.

Paris Green and other insecticides allowed farmers to cheaply and effectively protect their crops – and thus their livelihoods. In fact, less than 50 years after Ormerod’s death, chemist Paul Muller won a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the infamous (and environmentally catastrophic) insecticide DDT. When viewed in light of the “pesticide optimism” of her time, Ormerod’s enthusiasm about Paris Green is easier to understand.

Interestingly, Ormerod wasn’t just an insecticide evangelist. Her reports gave recommendations for a variety of pest control methods such as the use of exclusion nets and the manual removal of pests. These and other environmentally friendly techniques now form the core of modern “integrated pest management”, the gold standard for effective and sustainable pest control.

Eleanor Ormerod was devoted to the cause of protecting agriculture at a time when few “serious” entomologists were interested in applying their knowledge to agriculture. She recognised that progress in agricultural entomology could only happen when entomologists worked in close partnership with farmers.

She continued working and lecturing to within weeks of her death in 1901; in all of her years of service, she was never paid.

Tanya Latty receives funding from the Australian Research Council, The Branco Weiss Foundation and AgriFutures Australia. She is affiliated with The Australian Entomological Society.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.