Your smartphone can take a photograph with its inbuilt camera, but can it also print one? That is where instant cameras score brownie points. The return of all things retro may have catalysed their popularity, but it would be naïve to believe that instant cameras and films are a thing of past. They have been around in India for over a decade now and shutterbugs are clinging to them for the aesthetic, tactile quality they bring to photographs.

Chennai-based photographer Radha Rathi defines her artsy explorations with the Fuji Instax camera, gifted to her by her photographer friend Madhavan Palanisamy on her birthday, as “sheer joy”.

In 2015, when she set out to click pictures for Puducherry-based fashion designer Naushad Ali’s Spring-Summer campaign ’16, she opted for an instant camera. “Naushad’s signature style is easy and relaxed, yet warm and colourful. I wanted to replicate that ease, which comes naturally to shooting with instant cameras. You don’t have to create an artificial setting with lighting and other props. Instant films are a mood, with warm-toned, nostalgia-infused hues peculiar to Polaroids,” she says.

Eight years later, Radha’s love for instant cameras has not faded. She used them in a project for Calcutta-based fashion brand Aish in 2022 and shot a new series with them last year in Sri Lanka.

Selling like hot cakes and how!

Instant films and cameras were introduced and popularised by a Massachusetts-based company, Polaroid, in the 1940s. The company saw meteoric success in the ’70s, before it got buried in debt during the ’80s and filed for bankruptcy in the early 2000s. Its resurrection in 2008 by the Impossible Project, rebranded as Polaroid in 2020, catalysed the return of instant cameras.

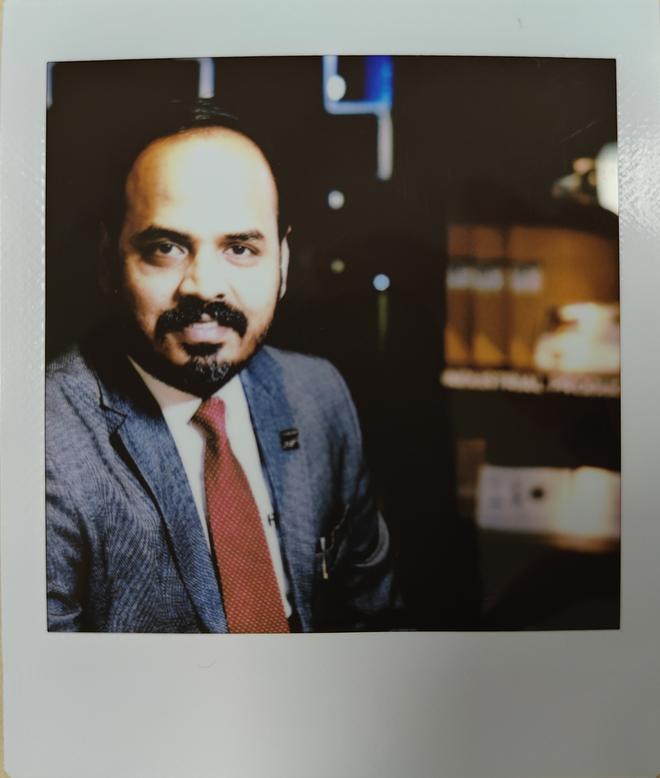

Polaroid has not forayed into India yet, but the country’s instant camera market seems to be bustling. “Presently, Fujifilm and Lomography are the sole brands offering instant cameras and films in India. We are observing a 30%-40% annual growth in instant camera sales. The majority prefers Fujifilm Instax. The sales of Lomography cameras are lower,” says Raychand Jain, proprietor of Foto Trade, Chennai.

The big player

Nostalgic quality

“I saw my first instant photo as a child in my dad’s collection, sent by his pen-pal from the US. Years later, maybe in 2011, I purchased a used Polaroid camera from a thrift store in the US but it stopped working after a few months,” recollects Gayatri Nair, co-director of Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB).

A professional photographer since 2011, Gayatri says in comparison to a film camera, an instant variant takes a lot less work to produce an analog image, but the trade off is that there is a lot less control over the quality of the image. “The low-resolution, blurry, flash-lit images produced by instant cameras have a nostalgic quality, which could be appealing to those experimenting with tones and textures,” In 2011, there was a resurgence of instant cameras, which prompted me to buy a Fujifilm Instax Wide. I use the camera for work as well as personal use and I love it,” she says.

For art’s sake

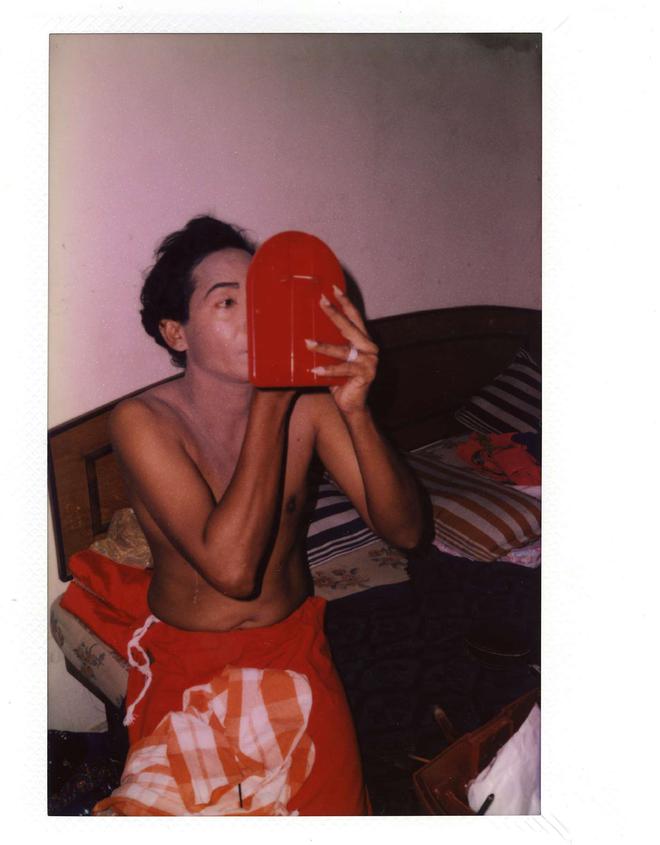

Fujifilm’s Instax Square SQ6 became Delhi-based photographer Karanjit Singh’s trusty sidekick during the first wave of the pandemic. With no access to photo labs during the lockdown, Karanjit used it to shoot obscure corners of his house, self-portraits and other objects to build a narrative of contrasts.

“In 2020, when I returned home after 15 years of staying in boarding schools and then in New York, where I did my BFA in Photo and Imaging from New York University, I found myself struggling to fit in. The gnawing depression was staring me in the face. Growing differences between me and my father, on political and spiritual account, and that I was diagnosed with tuberculosis all at the same time, was taking a toll on me,” he says. He is working on an instant film photography project, named after Punjabi writer Waryam Singh Sandhu’s short story Main Hun Theek Thaak Haan (I’m Fine Now). “It was important then, to take self portraits and explore the body as a battleground,” he adds.

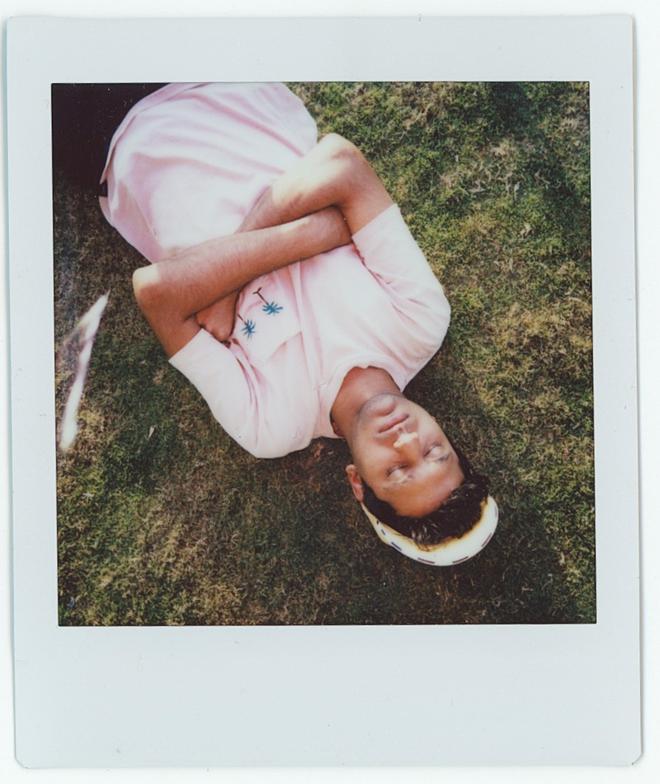

Jaisingh Nageswaran from village Vadipatti in Tamil Nadu has also shot a series, The Lodge, clicked at the lodges of Koovagam during the Koothandavar festival, on an instant camera. The Lodge was displayed at the Kyotographie Photo Festival at Kyoto, Japan, where Jaisingh was selected as the Grand Prix winner for 2023. He was introduced to instant cameras, when he was a child, by foreign tourists who clicked his pictures.

“While clicking the series on the transgender community, I tried digital and film camera, but something was missing. In 2015, a friend gave me an instant camera, Fujifilm Instax Wide 300. I was quite satisfied with the mood it sets,” he says. “It does slow me down, loading 10 films, but it also allows transparency and openness as people who I photograph can see what I am clicking,” he adds.

For the masses, not galleries?

Instant films may find an intimate spot in personal collections, but they have rarely made it to mainstream galleries of India. Karanjit shares his series was inspired by Greek-American artist Lucas Samaras, known for experimental self-portraits on Polaroid SX-70. Ever since their advent, Polaroids and other instant cameras have served as a creative medium for many, from pop art legend Andy Warhol to ace photographer Ansel Adams. Some of the iconic Polaroids include Andy Sneezing (1978), Walker Evans’s Abandoned House (ca. 1973-1974), Ansel Adams’s Yosemite Falls (1979) and David Hockney, Imogen + Hermiane Pembroke Studios (1982).

Gayatri feels that instant cameras are an accessible form of photography and perhaps that could be a reason they haven’t reached those elevated standards of high art . “Because anyone could do it — you just point and shoot and there is little you can control in the camera (in contrast, a high-end DSLR allows for a lot of controls). I’m not aware of many Polaroid-based exhibitions in India. Maybe that will change soon,” she says.

To Karanjit, the act of clicking pictures on an instant film is a deliberate, meditative process that’s restricting (because one doesn’t have many controls on an instant camera) and liberating at the same time. “You’ll find gatekeepers everywhere, but the merit of photography never lies in the medium he chooses to work with. It’s the frame and contents that define a photographer’s art,” he says.

Looking back, with love

Aditya Arya, the director of Museo Camera Museum, dotes on the Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 (1948-1953), which is the oldest instant camera at his museum. “Most cameras in the collection are functioning, but films are not available,” he says.

He recollects shooting a project “for a big car company” on a Polaroid camera, years ago. “I think it must have been some five or 10 degrees and we were shooting in an open area. I kept wondering why the image isn’t showing only to realise later that the films had to be at a certain temperature for the image to appear on them. I remember keeping the film cassettes in my jacket to keep them warm,” he shares. Though Aditya enjoys working with the modern-day Fuji Instax, he misses the quality of the Polaroid. “They were true to colour,” he says.

Polaroid Land 1500 camera from the ’70s holds a special place in Delhi-based photographer Akash Ghai’s heart. It belonged to his grandmother and was passed on to him as a family heirloom. “That was the first time I saw a Polaroid camera. My grandmother painted and taught us the basics of painting, but I never knew she was interested in photography too,” he says. It was around 2019 when he laid his hands on the Polaroid and then went on to buy a Fuji Instant camera.

“I first used an instant camera when I was on my way out of photojournalism, finishing a photo editor gig at China Daily in Beijing. I felt limited by the label of a photojournalist and the medium itself,” he says. His instant film series, combined with phone images and other film formats, was exhibited at a group exhibition in 2018 at Kalakar Theatre, Saket. It was then published in the form of a zine, called Mood Swings. “The work was about capturing some of the extreme emotions and nuances one feels moving through life and documenting them in a fluid, organic manner through instant photos and cellular images,” he says.

Radha too has documented her romance with instant films in a passport-size catalogue, called Last Summer. The instant films have been digitised, scanned and packed with Madhavan Palanisamy’s free-verse. “The book retains the size of the films. I know they are not as sharp as the ones you get on a digital camera, but they are a tangible memory of a thought, a feeling,” she says.