Niki Savva doesn’t like Scott Morrison. In the very first chapter of Bulldozed, she describes him as “petty and vindictive.”

Savva was just warming up. After the revelations of Morrison having secretly taken multiple ministries, his colleagues presented him to her as “messianic, megalomaniacal, and plain mad.” “Often, he would screw his friends”, she quotes one as saying.

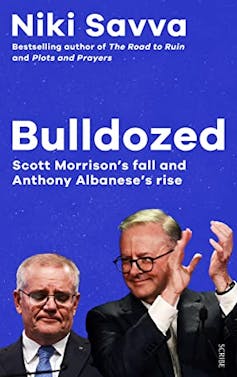

Review: Bulldozed: Scott Morrison’s fall and Anthony Albanese’s rise – Niki Savva (Scribe)

Fran Bailey, the former minister who pushed Morrison out of his job running Tourism Australia in 2006, thought him “missing that part of the brain that controls empathy.”

Voters “grew sick and tired of his weaving, wedging, dodging, fibbing, and fudging,” Savva judges. He was “Boris Johnson without the hair or the humour.”

In case we should remain in doubt after almost 400 pages, many of them given over to Morrison’s nasty, duplicitous and nutty behaviour, we get a summing up in the “acknowledgements” section. In most books, this is reserved for affectionate expressions of gratitude. Not here.

“He was woeful”, says Savva, “the worst prime minister I have covered.” “He simply wasn’t up to the job.” She apologises for whatever part she played in his rise.

Savva played little part in his rise but her commentary over recent years in the pages of The Age and Sydney Morning Herald probably did play some small part in his downfall. That said, there is sufficient damning material here to indicate that Morrison was primarily responsible for his own undoing.

He was also, as Savva shows, on the receiving end of a professional Labor outfit that, under Anthony Albanese, had learned from its previous mistakes and was single-minded in its pursuit of a pathway back to power.

Bulldozed is a big, sprawling book. Sometimes, it sprawls a little too much. The narrative can jump around in a way that might confuse those not already familiar with the broad outline of events. Savva is not one of the country’s great prose stylists, but there are lines here that only the humourless would complain about, such as Barnaby Joyce being “to Liberal voters what Roundup was to weeds”.

As in Savva’s account of another lamentable prime ministership, The Road to Ruin: How Tony Abbott and Peter Credlin Destroyed Their Own Government (2016), she presents politics as a human drama, played out by real (if highly unusual) people with ordinary (and, too often these days, extraordinary) human frailties.

Savva was herself senior media adviser to former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello, and the sensation is often that of the insider looking out and explaining to the rest of us how the system works and what its players are like. Savva manages to do so without talking down to her readers or sounding full of herself.

Opportunism and capitulation

This is a book of cumulative detail – a great deal of it damning to the Morrison government and flattering to its opponents – rather than of the grand revelation. Savva has excellent sources, but it is obvious there are too many people still pulling their punches, or simply not speaking at all, to permit a grander exposé.

At the time of writing, some of Savva’s discoveries have already been reported in the media. For instance, we now know that Yarralumla is an underestimated Canberra performance space, where guests at Government House are expected to sing to one another, often using lyrics provided by the wife of the Governor-General, Linda Hurley, set to some familiar tune. You Are My Sunshine was, according to Savva, “a hot favourite”.

This is a Canberra bubble – to use one of Morrison’s own favourite terms – a city full of spineless senior public servants, a prime minister and governor-general bereft of judgement, and a frontbench of opportunists willing to agree to anything so long as it ensured a smooth passage for their own glorious careers.

Some, including Morrison himself, appear not to have even a Year Nine civics class understanding of parliamentary government. Ben Morton, part of Morrison’s circle and an assistant minister, complains about people “hyperventilating” in the wake of the revelations about Morrison’s multiple ministries.

“Hyperventilating” is a classic word of the Australian political elites, of the kind used to ridicule those who seek to make them accountable for their own bad behaviour. The rest of us, it is implied, need to get with the program.

Then there is Keith Pitt, a National, and the only minister whom Morrison actually seems to have overruled while secretly holding one of his five fabled ministries.

“Pitt told me he seriously considered resigning”, Savva reports. Yet he did not, even though he knew Morrison had so egregiously breached the principle of ministerial responsibility.

And then there are the so-called moderates, whom Savva reveals to be moderate only in their willingness to do anything that might have harmed their own careers. With just a few honourable exceptions among the backbenchers, they capitulated on almost every occasion. Ministerial “moderates” lent their authority to trying to get dissenters to toe the line, such as over the issue of protections for transgender kids and teachers.

A party in tatters

Savva writes from a point of view. It is not just that she dislikes Morrison; she loathes what the Liberal Party has become under the sway of his style of right-wing populism. The party Savva values is the broad church of the Menzies era, more Melbourne than Sydney, one with a genuine liberal approach in matters of process, and a genuine commitment to principle and progress.

“We have to get back to the live-and-let-live ethos of the Liberal Party,” Liberal Senator Andrew Bragg tells her. Savva would agree.

That party was rooted in everyday Australian life, and it sought to appeal to women as well as men, unionists and bosses, pensioners alongside migrant communities and youth.

This Liberal Party now lies in tatters, captured by minorities of cranks and extremists, beholden to fossil fuel interests, and with increasingly tenuous links to the lived reality of the nation. Many of its leading members denigrate the values and lifestyles of those they need to support them. The party has a massive problem with women.

Several of the politicians who flourished in the Morrison era seem to spend a great deal of time praying together while their party collapses around them. Morrison even does the occasional laying on of hands.

Savva does not sustain an argument across the book about whether the key to understanding Morrison’s frankly weird political behaviour has his religious fervour at its heart, but there are enough stories offered here to suggest as much – something too many of her fellow journalists have refused to take sufficiently seriously.

Morrison might not really be the country’s worst prime minister. The government’s competent management of the pandemic during much of 2020 will likely save him from that fate. But he will surely be recalled as one of its strangest, and his government as possibly its most squalid.

Future historians may well puzzle over how a man so lacking in the qualities required in national leadership managed almost four years in office, rather as they wonder today how someone like Billy McMahon could ever have assumed the top job.

The Liberals’ foundation story is of a party made by Robert Menzies. That is not quite a reflection of historical reality, but the legend has its own power. Morrison, for his part, did not single-handedly destroy the party of Menzies, but his outsized role in its humiliation at the 2022 election and in its present disarray means that he may well be remembered for having done so.

If that idea does indeed gain force, Bulldozed will be one of the texts to which the true believers in Morrison as the wrecker of the Liberal Party will turn for support.

Frank Bongiorno does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.