A culture in gymnastics that has tolerated coaches belittling, manipulating and in some cases physically abusing young athletes is being challenged by Olympians and other gymnasts around the world after an uprising in the United States.

Many current and former competitors, emboldened by their American peers, have broken their silence in recent weeks against treatment they say created mental scars on girls that lasted well into adulthood.

One gymnast, who is just 8 years old, says a coach tied her wrists to a horizontal bar when she was seven and ignored her as she cried out in pain.

At a time when the Tokyo Olympics would be in session had they not been postponed until 2021 by the coronavirus pandemic, gymnasts have been sharing horrific stories of coaches body-shaming them, stifling their emotions, using corporal punishment on them and forcing them to train with injuries, using the pursuit of medals as a way to rationalise shameful behaviour.

Chloe Gilliland, 29, a former member of the Australian national team, recalls her coaches telling her that she was “a bad child” and “a danger” to her own body because she was too heavy. At 17, she thought of killing herself because, she says on Instagram, “I felt like it was easier to end my own life than to give in to what they wanted me to be.”

Catherine Lyons, 19, once a top junior competitor for Britain, says coaches would hit her and harass her about her weight, and when she was 7 or 8 she would cry so hard that coaches would shut her inside a cupboard until she composed herself. Later, she says, she learned she had post-traumatic stress disorder because of the treatment. She told ITV News: “I wasn’t worth anything. I wasn’t a human. I was a commodity rather than a child.”

Other gymnasts have simply said on social media, “I am one of them.”

The stories from gymnasts in all levels of the sport are part of a coordinated effort, similar to the #MeToo movement, calling for the sport’s leaders to eradicate existing norms that in reality are not normal at all.

“I was told many times that gymnasts should be seen and not heard because the sport is all about being the good little gymnast,” says Lisa Mason, a 2000 British Olympian who was among the gymnasts to speak out recently.

Mason, 38, says her coaches threw shoes at her and scratched her when she did not perform perfectly. Once she was made to stay on the uneven bars until her hands were blistered and ripped, only for a coach to pin her hands down and pour rubbing alcohol into her raw wounds.

Looking back, Mason calls the atmosphere “insane,” especially because gymnasts who start training seriously at a very young age are often left alone with coaches.

“So many of us are done with normalising the abuse that we were told was needed to make champions,” Mason says. “We want change, and it’s incredible that so many of us are coming together to demand it.”

The gymnasts have made an impact. National gymnastics federations in Britain, Australia, the Netherlands and Belgium have begun investigations or requested enquiries into alleged abuse, with the Dutch federation saying it would suspend its entire women’s national team programme as it looked for answers.

Jennifer Pinches, a 2012 British Olympian, says this most recent global push to change the sport was sparked by a Netflix documentary, Athlete A, which depicts the harrowing training of American elite gymnasts and the cover-ups that surrounded USA Gymnastics’ sexual abuse scandal involving its longtime doctor, Larry Nassar.

“It was a tipping point that enabled this movement to happen,” says Pinches, who saw the film when it was released in late June and persuaded more than 30 British gymnasts, including Mason, to post a joint statement on social media condemning “the culture that didn’t put athlete health and wellbeing first and allowed Nassar to act”. Mason, who had already posted a scathing Instagram commentary on the sport’s culture, suggested that the group use the hashtag #GymnastAlliance. Now, there have been more than 700 posts with related tags on Instagram alone.

Back in the United States, Jennifer Sey, a 1986 national champion and one of the producers of Athlete A, is stunned that the film prompted so many athletes to come forward about their experiences, especially when athletes had so many previous chances to speak up.

Over the last 25 years, there have been several books about abuse in the sport, including one by Sey in 2008. There also were Nassar’s sentencing hearings in 2018, during which more than 150 girls and women spoke out about his molesting them. Many said the sport’s culture of fear and silence made them vulnerable to Nassar’s abuse.

In April, Maggie Haney, who coached Olympian Laurie Hernandez and other gymnasts, was suspended for eight years by USA Gymnastics for verbally abusing and mistreating athletes. It was among the first times – if not the first – that a top American coach had been punished for that kind of abuse.

Yet gymnasts see this moment in 2020 as a perfect time to bring worldwide change to nonsexual abuse in the sport.

“This time, you can’t say the accusations are against just one bad apple, one bad coach or one bad system, and then dismiss them,” Sey says. “I think a lot of these women who came forward continued to suffer because of their coaches’ cruel treatment, and they don’t want to suffer anymore. They don’t want future generations to suffer, either.”

The timing makes sense to Cheryl Cooky, an associate professor at Purdue University and a sociologist who studies gender and sports.

“People have been more reflective of their lives during this pandemic, and for athletes, it’s not a time for the Olympics or a time to just focus solely on your sport,” she says. “They can take time to step back and think about some important philosophical or existential questions.”

In speaking up, some athletes have been forced to process some dark memories.

Athlete A prompted Olivia Vivian, an Australian star of the reality competition Ninja Warrior and a 2008 Olympian, to surface troubling memories of her gymnastics career that, according to an Instagram post, she had packed away “deep, deep down”.

It was the first time she thought about the culture of fear in gymnastics, she says in a telephone interview, and she was overwhelmed because she always considered the mistreatment to be normal. She says her coaches often yelled and threatened her, saying the gym would lose funding if she did not make the world team. She recalls them using her as an example to younger girls of what it takes to be a hard worker, bringing them to her so they could see her torn-up, bleeding hands. They would say, “You need to push through like Olivia pushes through,” she says.

The pressure and stress broke Vivian after the 2008 Olympics, she says, and it took the positivity of gymnastics at Oregon State University and the Ninja Warrior community to build her back up. Still, since Athlete A, Vivian has turned to a psychologist to work through her sadness and guilt over not speaking up sooner so she could have saved other gymnasts.

“It’s going to take a bit of time for me to work through this,” Vivian says. “But I’m glad I told my story for the sake of the sport and maybe give other gymnasts the strength to stand up.”

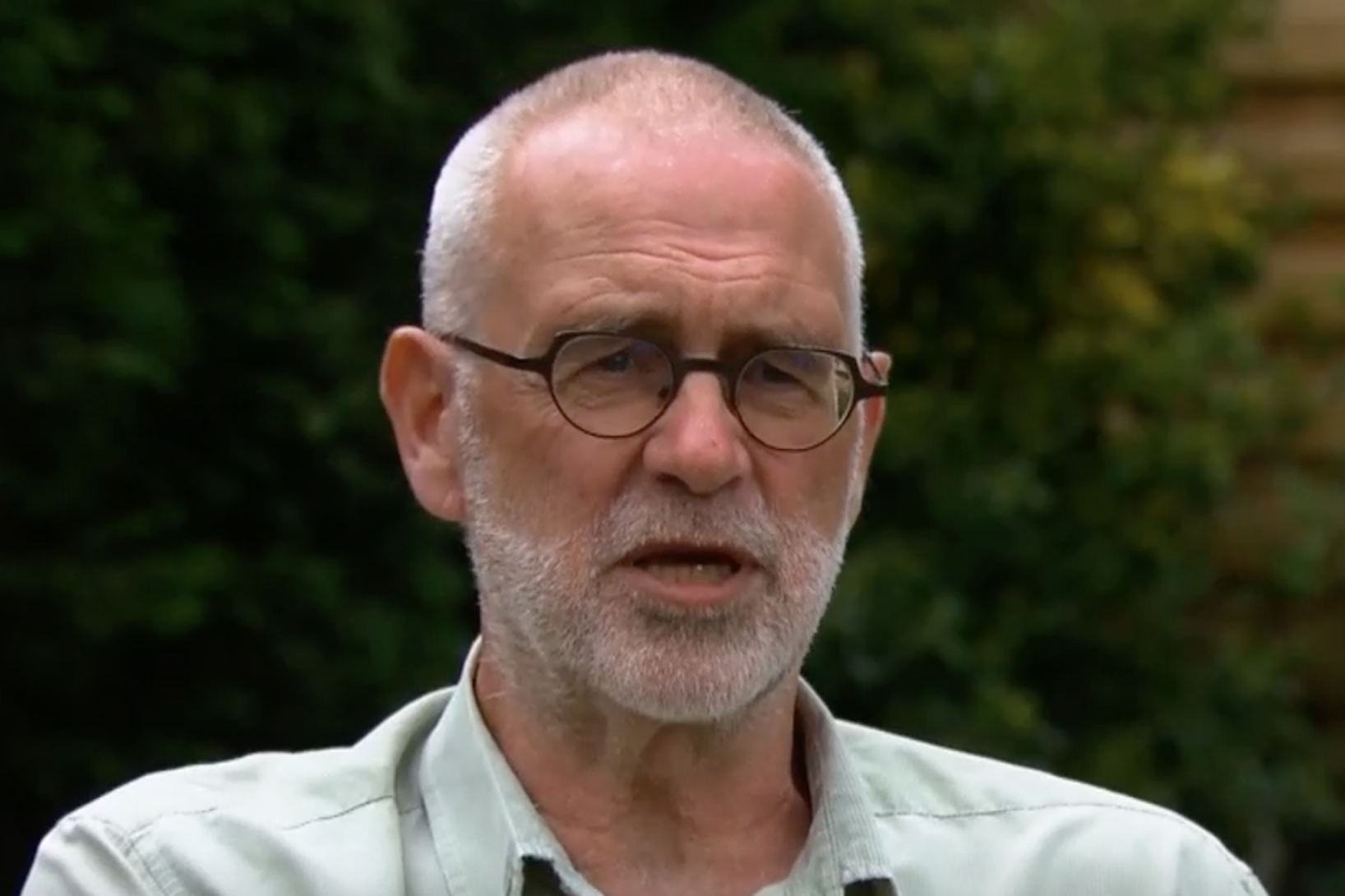

One person familiar with the abuse gymnasts like Vivian have described is Gerrit Beltman – because he used to coach that way. In 2013, Beltman was the subject of a book that accused him of tyrannical behaviour while coaching the Dutch national team. He has also coached elite teams in Canada, Belgium and Singapore.

But in late June, as part of an investigation by the Dutch newspaper Noordhollands Dagblad, Beltman apologised for his actions and said he was “ashamed”. Ten current and former Dutch national team gymnasts came forward with accusations of abuse in that report.

“It was never my conscious intention to beat them, to yell at them, to hurt their feelings, to belittle them, to gag them or make constant derogatory remarks about their weight,” Beltman said in Dutch. “But it did happen. I went too far because I thought it was the only way to instil a winning mentality in them.”

He said he copied techniques from colleagues and previous coaches who had delivered many champions. When coaching in Canada, he said in the newspaper report, he realised that his style needed to change.

Now Beltman says a shift in the sport is “a matter of bitter urgency”, and his daughter Reina agrees. She was an alternate on the Dutch Olympic team for the 2016 Rio Games and coached by her father when she was young. She was among many Dutch gymnasts who posted on social media about past abuse, later explaining in an interview that she has struggled with low self-confidence as a result. When asked about her father’s coaching, she declined to comment.

Reina Beltman does say, however, that her father’s decision to speak about his past means there is hope for the sport.

“The best thing that could happen right now is for coaches to be honest and apologise for what they’ve done, so the gymnasts and the sport can move on,” she says. “We just have to have this conversation, and, of course, changes won’t be made over one night, but it’s a beautiful thing to take responsibility and try to make things better.”

The next step, says Mason, the British Olympian, is for the sport to create a way for athletes to report abuse to an independent organisation without fear of retribution by their federation or coaches, who have the power to keep them off top teams, including a national or Olympic team. Many athletes who recently came forward told Mason they did not trust leaders in the sport to investigate coaches.

It is no wonder they are sceptical: some athletes and leaders still doubt that emotional abuse is real.

Liubov Charkashyna, a former Belarusian rhythmic gymnast, is the president of the athletes’ commission at the International Gymnastics Federation, the world’s governing body for the sport. One of her jobs is to listen to athletes’ concerns and fight for athletes’ rights inside the federation. But in 2019, she said the number of women who said they were abused by Nassar was exaggerated because some women were just trying to get revenge on their former coaches or earn money.

And last month, the former gymnast Svetlana Khorkina of Russia, a three-time Olympian and 20-time medal winner at the world championships whose voice is still powerful in the sport, told Sport Express that the recent wave of abuse allegations was silly.

“There are certain things in the profession that are necessary for success,” she said in Russian to the sports newspaper, and asked why the gymnasts just did not quit the sport, leave the coaches or file lawsuits. “It’s just self-promoting, ugh!”

Athletes hesitated out of fear and uncertainty because abuse was so normalised, Mason says. She says she was disappointed, but not surprised, to hear Khorkina’s comments because “when you tell a difficult truth, there will always be people trying to discredit you”.

Still, Mason expects more gymnasts to call for changes in the sport. She says she had heard from many gymnasts training for the Tokyo Games who would not come forward until the Olympics were completed in August 2021. They do not want to jeopardise their chances of being chosen for their team, she says.

Those competitors are just some of the many women who have reached out to Mason since she first posted about Athlete A, to share their experiences and vent. They say they no longer feel so scared and alone.

“We have a great chance at changing the sport because so many of us are finally being heard,” Mason says. “There’s so many of us, and we’re so loud that you can’t ignore us.”

© The New York Times