Earlier this year, Governor Greg Abbott ordered his longtime mentee and newly appointed Secretary of State David Whitley to purge the Texas voter rolls of suspected noncitizens. It was bungled from the start. Whitley’s office flagged nearly 100,000 registered voters for citizenship review, which Abbott and others promptly used to stoke fears of rampant voter fraud. But nearly a quarter of the names on the list were included by mistake and many more were naturalized citizens. The state was sued for voting rights violations and Congress launched an investigation before Whitley eventually agreed to shutter the whole thing. Despite the governor’s best efforts, Democrats in the state Senate blocked Whitley’s confirmation and he resigned on the last day of the legislative session.

On Monday, Abbott finally appointed Whitley’s replacement: Ruth Ruggero Hughs, who was chair of the Texas Workforce Commission, an agency with a sprawling mandate that includes enforcing state’s labor laws and administering unemployment insurance.

As secretary of state, Hughs, who is originally from Argentina, is charged with overseeing the state’s elections, among other duties, while also restoring the public’s trust, particularly of Hispanic Texans who were wrongfully targeted by Abbott’s attempted purge. “As an immigrant to America & now a citizen of our great country she cherishes the right to vote & will ensure that right is safeguarded,” Abbott tweeted Monday.

But as the Texas Observer has previously reported, Hughs was plagued by her own scandal over an industry-written rule she enacted during her time at the Texas Workforce Commission.

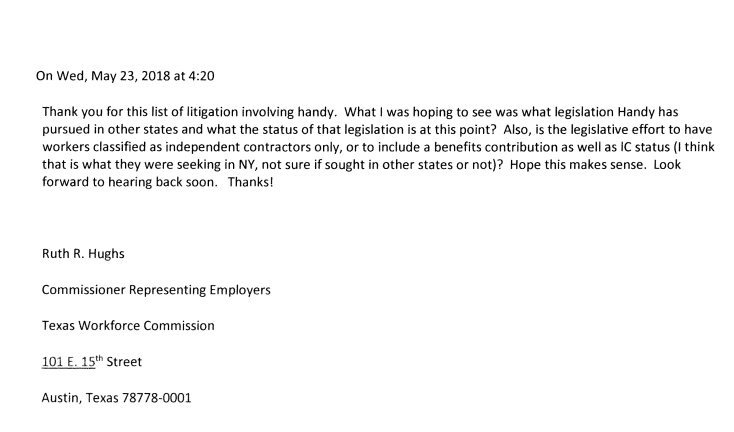

In March, the Observer obtained emails from a public records request that showed Hughs had been secretly coordinating for more than a year with lobbyists for Handy, an on-demand company that had been pushing “marketplace contractor” legislation in states across the country. In Texas, the lobbyists wanted to make an end-run around the Legislature by going straight to the regulator, providing Hughs and her staff with draft language that proposed a dramatic rewrite of state labor regulations that ensured that gig workers would be ineligible for unemployment insurance. Hughs was eager to help, emails showed.

When news of the rule first surfaced in January, the commission denied that there was any outside involvement. “Neither staff nor the Commissioners use outside sources when drafting proposed rules,” Lisa Givens, the agency spokesperson, told the Observer in January.

Hughs said nothing. Then, when public records were released two months later showing Hughs’ direct coordination with Handy lobbyists, the commission offered another explanation. “When I provided my response to you … I was not aware of meetings referenced in email records,” Givens said in a statement, adding that it was common for the Commission to work closely with industry to craft regulations.

The Observer also discovered the two Austin lobbyists—Jerry Valdez and Mackenna Wehmeyer—working with Hughs on behalf of Handy had never registered the company as a client, a violation of state law that ensured the company’s role remained a secret.

The Commission repeatedly declined to make Hughs available for an interview and she did not respond to emails with detailed questions about her involvement.

However, Hughs did defend herself and the rule in a letter responding to concerns detailed in an inquiry by state Representative Ramon Romero, including whether Hughs was aware that Valdez and Wehmeyer had failed to register as working with Handy. “No one in my office knew, inquired about, or investigated the registration status of the employer representatives, nor is that required,” Hughs wrote. She insisted that the process was entirely above board. She also defended the regulatory changes, which passed in April, saying they were simply about providing legal clarity for gig workers and digital platforms, and wouldn’t undermine the rights of traditional employees.

Hughs’ aversion to transparency in the face of public scrutiny is not a reassuring sign for the advocates and lawmakers who hoped that Abbott’s new secretary of state would help restore the damage done by Whitley. Abbott is entitled to appoint officials during interim periods between legislative sessions, meaning that Hughs won’t have to face the state Senate for confirmation until January 2021 at the earliest.

“Needless to say, this raises questions about the commissioner,” said state Senator José Rodríguez, who heads the Senate Democratic caucus and helped block Whitley’s confirmation. “And so I think we’re going to be looking closely at her nomination. At least I will.” Hughs’ behind-the-scenes collaboration with lobbyists to enact a substantive new policy without the Legislature was a “red flag,” Rodríguez said.

“She has a track record of putting corporate interests before people and we have no reason to believe that her actions will be any different as secretary of state,” said Jose Garza, co-executive director of the Workers Defense Project, a labor group that organized against the marketplace contractor rule.

The secretary of state has traditionally been a low-profile position used by governors as a sinecure for political allies. But in the wake of the Whitley debacle and with a presidential election coming up, all eyes are on the post. A lawyer by trade, Hughs worked for Abbott in the mid-2000s when he was the Texas attorney general. She defended state agencies from civil rights and employment lawsuits, and was eventually put in charge of Abbott’s civil litigation department.

One unresolved question from the Handy handout was whether Hughs was pushing the marketplace contractor rule through her agency under orders from the governor. Public records requests for communications between the Workforce Commission and the Governor’s Office were exempted from release because they were part of “deliberative process privilege.”

The few records that were released included emails from April in which Givens, the TWC spokesperson, shared the Observer’s story about Handy’s illegal lobbying and the passage of the final rule with three of Abbott’s top aides, including his deputy chief of staff and communications director Matthew Hirsch. In another email, Givens updated one of Abbott’s top policy advisors about media inquiries she had received after the commission approved the final rule.

Hughs was vague about the governor’s role in her letter to Representative Romero. “I speak to the Office of the Governor to keep them updated on my work at TWC. Furthermore, as requested of all state agencies, TWC advised the Governor’s office of the draft rule.”

The Governor’s Office did not respond to a recent request for comment about Hughs’ coordination with lobbyists and the extent of their role in the rule’s passage. Givens said “I do not have anything further to add” beyond what was made public via records requests.

Read more from the Observer:

-

How Silicon Valley Lobbyists Secretly Pushed Texas Regulators to Rewrite the Rules of the Gig Economy: Documents show that lobbyists for Handy.com dictated a rule to the Texas Workforce Commission that would give legal shelter to gig economy companies who don’t want to treat workers like employees.

-

Texas Is at the Center of Trump’s Anti-Immigrant Facebook Ad Campaign: His reelection campaign has spent big money in Texas on a digital advertising effort, which includes more than 2,000 Facebook ads warning about an “invasion.”

-

Where the Bodies are Buried: In 1910, East Texas saw one of America’s deadliest post-Reconstruction racial purges. One survivor’s descendants have waged an uphill battle for generations to unearth that violent past.