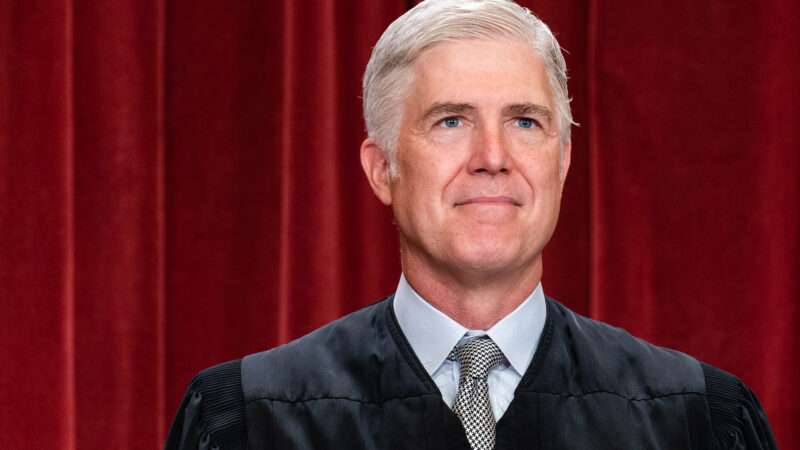

Justice Neil Gorsuch says all three branches of government share some of the blame for what he calls the "breathtaking scale" of emergency powers wielded by public officials during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"While executive officials issued new emergency decrees at a furious pace, state legislatures and Congress—the bodies normally responsible for adopting our laws—too often fell silent," Gorsuch wrote. "Courts bound to protect our liberties addressed a few—but hardly all—of the intrusions upon them."

Gorsuch's sweeping and powerful statement was attached to the Supreme Court's recent ruling in Arizona v. Mayorkas, one of several cases dealing with the Title 42 orders that allowed federal immigration authorities to expel migrants seeking asylum in the United States. Title 42 had been invoked by former President Donald Trump as the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, and it was repeatedly extended by both Trump and President Joe Biden before finally being brought to an end last week.

But Title 42 was just one in a litany of COVID-related emergency powers that drew Gorsuch's ire.

"Since March 2020, we may have experienced the greatest intrusions on civil liberties in the peacetime history of this country. Executive officials across the country issued emergency decrees on a breathtaking scale," Gorsuch wrote before rattling off a list that included stay-at-home orders, school closures, attendance limits on churches, a federal ban on evictions, and the Biden administration's attempt (blocked by the Supreme Court) to impose a national vaccine mandate via a federal workplace safety regulator.

As some Gorsuch critics have been quick to point out on Twitter, it might be a bit of an exaggeration to call this the "greatest" attack on civil liberties in American history. There are unfortunately more than a few other contenders for that ignominious crown: slavery, Jim Crow, the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War. All were, like COVID-19 emergency powers, the result of legal exercises of state power that violated basic civil rights.

But what the country experienced over the past few years does not have to top that list to be worthy of serious disdain. Gorsuch's statement shouldn't be regarded as a hot take about the worst civil liberties violations in American history, but a thoughtful review of how governments failed in this instance—so that they might do a better job in the future.

"Doubtless, many lessons can be learned from this chapter in our history, and hopefully serious efforts will be made to study it. One lesson might be this: Fear and the desire for safety are powerful forces. They can lead to a clamor for action—almost any action—as long as someone does something to address a perceived threat," he wrote. "We do not need to confront a bayonet, we need only a nudge, before we willingly abandon the nicety of requiring laws to be adopted by our legislative representatives and accept rule by decree. Along the way, we will accede to the loss of many cherished civil liberties—the right to worship freely, to debate public policy without censorship, to gather with friends and family, or simply to leave our homes."

This is, as Gorsuch also notes, not a new lesson but one that has been part of the story of democracy since ancient times.

Even so, it's a lesson worth revisiting in the aftermath of the pandemic. If there is one thing that ought to change, it's probably the general understanding of what constitutes an emergency in the first place. By definition, it is an acute, immediate crisis. But during the pandemic, that definition was stretched to include adjacent policy issues that had nothing to do with the immediate public health situation. An eviction moratorium never made much sense as a response to a viral outbreak, at least not after stay-at-home orders were lifted. Neither did cross-border travel restrictions after the pandemic's earliest days when it was hoped (wrongly) that such barriers could keep the disease at bay.

"The point of an emergency is that it's a sudden, unforeseen, urgent kind of scenario," says Jonathan Bydlak, director of the Governance Program at the R Street Institute, a right-of-center think tank. Bydlak, my guest on this week's episode of American Radio Journal, compares it to a car accident: a situation where the normal rules might have to be suspended—an ambulance can run red lights, for example, to respond to the call. Months later, however, when an accident victim might be on his way to physical therapy, he doesn't get to bypass the red lights.

"Sometimes people conflate the initial crisis—the initial instigating event—with this broader question and say 'just because something important is going on, it must be an emergency' and that's not necessarily the case," says Bydlak.

That's exactly what happened over and over during the pandemic. Just look at the Title 42 saga, which Gorsuch said was an example of government officials prolonging "an emergency decree designed for one crisis in order to address an entirely different one."

"In some cases, like this one," he added, "courts even allowed themselves to be used to perpetuate emergency public-health decrees for collateral purposes, itself a form of emergency-lawmaking-by-litigation."

Emergencies may sometimes require that the lawmaking process be temporarily short-circuited, but it's imperative that state legislatures, Congress, and courts at all levels tighten up the circumstances in which emergency powers may be invoked. Gorsuch is right: When officials take shortcuts to make policy, civil liberties are often the cost.

The post Gorsuch Condemns 'Breathtaking' COVID Emergency Powers That Crushed Civil Liberties appeared first on Reason.com.