Emma Pierson* can vividly remember the night her childhood ended. Woken by two burly strangers standing over her bed, the 15-year-old recoiled in horror and let out a blood-curdling scream, which ripped through her palatial family home in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Downstairs, Pierson’s mother, who had sole custody of her at the time, waited.

She had already signed the paperwork consenting to her child’s orchestrated kidnapping – an act of “tough love”, she reassured her daughter. Pierson didn’t put up a fight as the uniformed men

ushered her into the car. When they arrived at Sydney Airport, they led her through the terminal with her hands restrained in cable ties. There were only a few other travellers waiting in the pre-dawn light; heads turned and eyes widened as the group marched past.

One airport official pulled them aside, but the men showed documentation and continued to walk Pierson to the gate. Finally standing in the cramped aeroplane bathroom, she savoured her last few private moments. “I remember looking at myself in the mirror and saying, ‘You’ll make it. You’ll make it. It will all be OK,’” recalls Pierson, now 23. That evening, Pierson flew to Utah, in the US, and found herself in a “turn-about camp” for problem children.

What Happens Inside American ‘Brat Camps’?

Her chilling abduction was not unique: each year, thousands of young people are snatched from their homes and sent to similar facilities across the country – from wilderness retreats and boot camps to boarding schools – to treat supposed addiction, mental health issues and behavioural problems.

There are more than 1000 residential treatment centres for troubled youth in America, attended by 50,000 children annually. It’s big business, too: the nation’s Troubled Teen Industry (TTI) is worth $US2 billion a year, and parents with the financial means will pay upwards of $US30,000 (some have spent $US200,000 – almost twice the cost of a Harvard degree) to secure their child a spot.

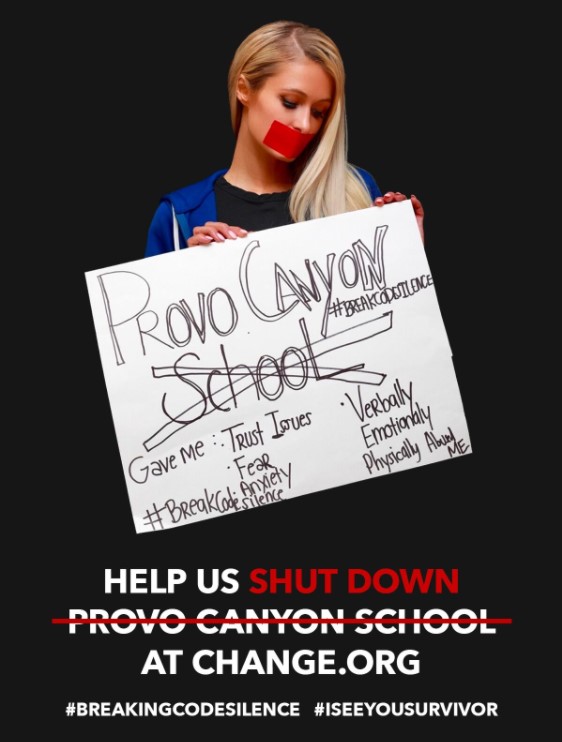

In 2020, these facilities came under the glare of the public spotlight following allegations of physical and mental abuse. In Paris Hilton’s documentary This Is Paris and her autobiography, Paris: The Memoir she spoke about her time at Provo Canyon School, a residential treatment centre in Utah, where she says she was beaten, put in solitary confinement and prescribed unknown pills. Like Pierson, she says strangers kidnapped her in the middle of the night – something she still has nightmares about.

Four years on, Hilton continues to campaign tirelessly to strengthen the child welfare system appearing before the House Committee on Ways and Means last month to testify that she was sexually abused and force-fed medication while in “treatment.”

“I was force-fed medications and sexually abused by the staff. I was violently restrained and dragged down hallways, stripped naked and thrown into solitary confinement,” she recalls.

Hilton spent a total of 11 months in the “torturous” facility, all because, she says, she’d been sneaking out to parties and clubs at 17.

Pierson, too, contests whether she was ever a bad teen. She attended a prestigious private school in Sydney and excelled academically, but at home things were difficult. Pierson’s mother had fallen head over heels for a new partner, a man Pierson alleges was eager to get her out of the picture. And so, on the night before her mother’s birthday, in February 2013, she was shipped of to the States.

There she spent two months at a ranch in the Utah desert. Her days were filled with “hard labour” in freezing conditions. She had to learn how to start a fire and pitch a tent or risk forgoing

food and sleep that night.

Among her new peers were a heroin addict and a girl who was sent to the program for sexually molesting her younger brother. The irony was not lost on Pierson that she’d been sent here because her parents thought she was hanging out with “the wrong crowd”.

No-one told Pierson when she’d be allowed to go home. Nine weeks later, her mother arrived to tell her that she wouldn’t be returning to Australia. “An educational consultant in New York had advised Mum that I should attend the Monarch School, a behavioural modification boarding school in Montana,” says Pierson, noting that such consultants receive hefty referral fees. (The Monarch School closed its doors abruptly in 2017, citing unsustainable student enrolment numbers. Parents reportedly sued the owners for malpractice and breach of contract, but there has been no response to abuse allegations.) “I felt completely powerless. I was so desperate to become autonomous and never look back, but there was no-one to save me.”

Over the next 18 months, Pierson says she was broken under institutional care. “I experienced this deep, deep depression. I was never depressed until I went there,” she says. “I thought about

killing myself several times because I didn’t know when it was going to be over.” She says the worst parts were the cruel punishments and highly controversial therapy treatments, such as

attack therapy.

“They would do these ‘challenges’ where you have to go into a dark room and look in a mirror and they would have people in the dark corners yelling horrible things at you. It was supposed to make you feel better about yourself.”

Hilton says her experience at Provo Canyon left her with lifelong trust issues. “I felt like a prisoner,” the 39-year-old told People magazine. “It was supposed to be a school, but [classes] were not the focus at all. I think it was their goal to break us down. They were physically abusive, hitting and strangling us. They wanted to instil fear in the kids so we’d be too scared to disobey them.”

Which Celebrities Were Sent To Brat Camp?

She’s not the only high-profile former student to speak out. Television personality and beauty mogul Kat Von D, 38, called the time she spent “locked up” at Provo Canyon when she was 15 “the most traumatic six months” of her life. She says she was strip-searched, made to shave her head and, after a range of medical tests, was led to believe she’d contracted HIV from her

tattoos – experiences she says left her with severe PTSD and led to her future alcoholism and drug use. Paris Jackson, daughter of the late Michael Jackson, has also deemed her time at a similar behaviour-modification boarding school “child abuse”.

Since then, more former Provo Canyon pupils have come forward with allegations of their own, including bullying and chemical sedation. There are also accusations of sexual assault, though the details remain vague.

Hilton alleges that from 2011-2014, police received 56 calls about assault and 25 calls about sexual offences at the institution. Despite the uproar, the school has remained relatively silent. A statement on its website reads: “Provo Canyon School was sold by its previous ownership in August 2000. We therefore cannot comment on the operations or patient experience prior to that time. We do not condone or promote any form of abuse.”

The Salt Lake Tribune reported that the allegations of abuse continued until as recently as 2017, though Utah’s Department of Human Services – which licensed the school – together with healthcare organisation The Joint Commission and educational non-profit Cognia, both of which accredited the school, all released statements insisting Provo currently meets their standards and all allegations of abuse are taken seriously. The Troubled Teen Industry has long enjoyed ties to big business and politics. Its model is believed to be based on Synanon, a 1960s support group that claimed to help troubled Hollywood stars.

By 1970, though, it had reportedly become an anti-drug cult that abducted addicts and attempted to rehabilitate them via beatings and humiliation. Dubbed in a news report as one of “the most

dangerous and violent cults America has ever seen”, it disbanded in 1991. Following its closure, a wave of tough-love schools emerged, some of which were endorsed by politicians. Straight, Incorporated – named for its stance against drug use – used extreme methods to reform troubled teens, and was praised by former first lady Nancy Regan and George W Bush. (There is no suggestion that they were aware of any abuse.) Two of the three co-founders of Straight were later named American ambassadors to Australia, Italy and Spain, and were major donors to the Republican party.

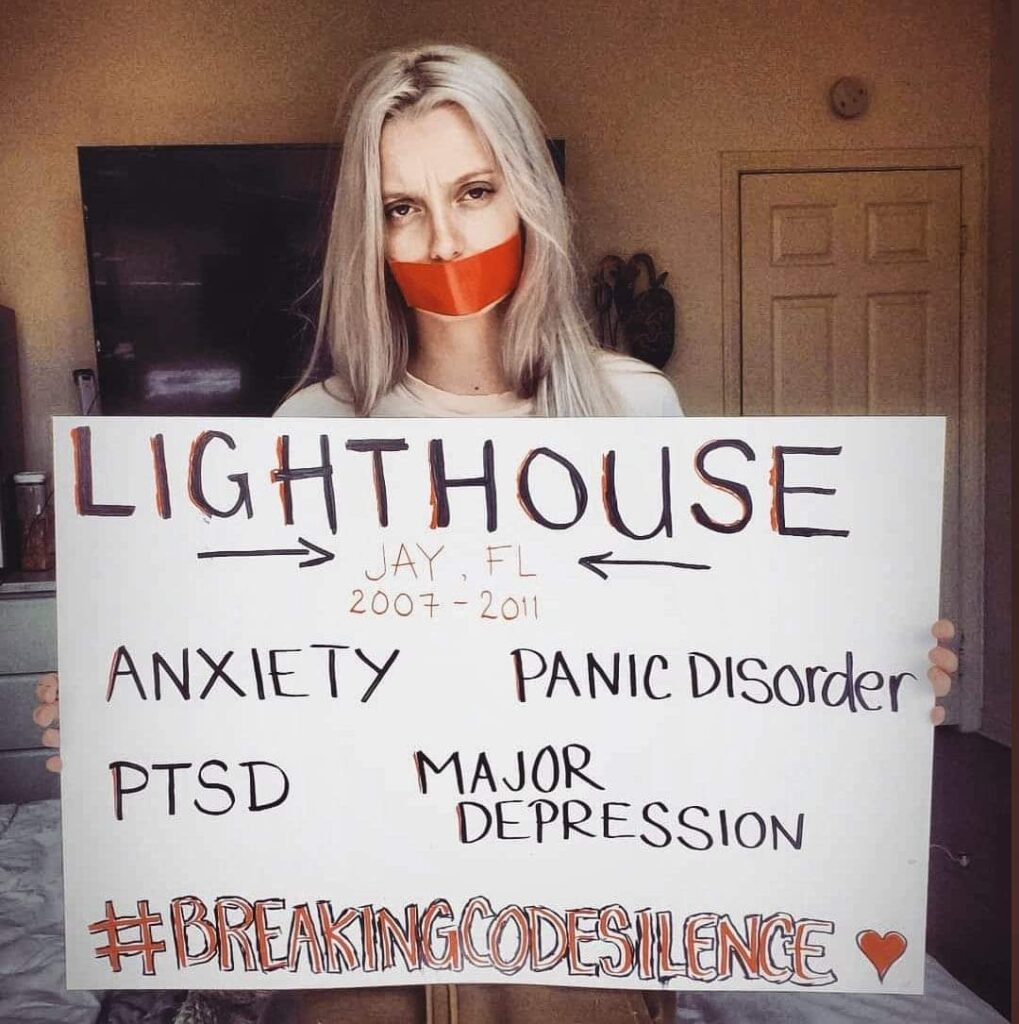

Hannah Kay, a survivor of Lighthouse in north-west Florida (a reform school that shut down in 2013), recalls undergoing similar practices to Synanon’s humiliation therapy. “They called it ‘rapping’,” says Kay, who is now 27. “Basically, they force everybody to rat on each other and if you don’t do it, [you are scared] somebody’s gonna say stuff about you. It was mental manipulation. Also, because we couldn’t use the bathroom all the time, girls would wet themselves and the staff would humiliate [them].”

Rapping was just one of the countless humiliations Kay endured at Lighthouse during her four-year stay. Upon arrival, the then-13-year-old was told to remove her clothes before being

strip-searched for any tattoos or concealed items from home. “That’s their way of taking that last strip of your identity before they give you a uniform to wear,” says Kay. Next, she was told she had to participate in the program’s exercise class, even though she was suffering from a stress-induced UTI, which she says came from the trauma of being kidnapped in the middle of the night. “I was in pain, but the leaders didn’t believe me,” says Kay.

“I wasn’t being active enough, so they tackled me to the ground. Facedown. They then sat several people on top of my body. They called it ‘flooring’. Your body just goes numb because there’s no blood flow anymore. It usually lasted [from] 30 minutes to a couple of hours.” One of the harsher punishments at Lighthouse was being banished to the Get it Right Room, a windowless, dingy room where girls could spend anywhere from days to months in isolation.

But Kay believes the most damaging punishment was not the physical abuse but the silencing, often referred to within the schools as Code Silence.

“There were maybe two hours a day that you were allowed to talk to other people, but even that was limited in content. You certainly couldn’t have any friends. Your calls and any letters

you wrote to your parents were monitored and if they didn’t like what you said they would rip up your letters or hang up the phone. You weren’t even allowed to write in a diary.”

The punishment, used in similar schools across the country, was the inspiration for #BreakingCodeSilence, a movement organised by former students and amplified by Hilton. Together with fellow alumni of the Troubled Teen Industry, Hilton is encouraging survivors to share their stories of abuse and mistreatment.

Cristina Mardirossian is a therapist based in California. She has treated a number of teenagers from these programs and has witnessed the lasting impact of institutional abuse. “Having to keep thoughts and feelings about these traumas to oneself is absolutely damaging,” she says.

“Trauma heals when it is heard and seen. These programs don’t hear you; they control you. They want conformity and obedience,” says Mardirossian. “When you are in a high-intensity environment like the TTI, you are kept in an incredibly deprived state, which keeps you physically exhausted, and which means you don’t have room to think and process your feelings. When

you don’t have an outlet to trauma, it is going to leak in some way.”

For TTI survivors such as Pierson and Kay, the abuse has left scars of self loathing, pain and mistrust. Both women have forgiven their parents, who they believe were also victims of an industry that preys on desperate families. Pierson’s mother has apologised for sending her daughter away, although Pierson still mourns her stolen teenage years. “I was robbed of seeing my brother grow up and of time with my dad. My mum got sick with Parkinson’s when I was there, so I missed the last years of her being healthy,” she says. “Some days are easier than others, but I don’t bother telling people [about my experience] because it’s too hard to understand. I don’t want to be perceived as a liar or have people think I was a bad kid who deserved it. I wasn’t.”

Kay, too, knows that the emotional turmoil lives on long after graduating from a TTI program. “I remember thinking I’m gonna walk out and I’m gonna feel free. I’m almost 18 years old, and no-one will be able to control me,” recalls Kay. “When my parents eventually did collect me, I waited for the bells and whistles and fireworks… and then it hit me. For the rest of my life, I’m gonna feel this. I wasn’t free; all this trauma was coming home with me. From the moment I walked out I knew – that cloud’s going with me.”

If you or anyone you know needs support, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

This article originally appeared on Marie Claire Australia and is republished here with permission.