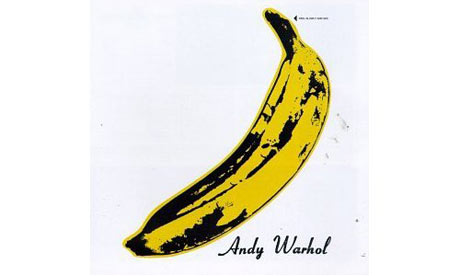

It's sad to see one of the great creative partnerships of the 20th century being picked apart in the courts. This week, a judge dismissed a copyright claim by members of the Velvet Underground against the Andy Warhol Foundation over the use of the famous yellow and black banana logo that Warhol designed for their first album, released in 1967.

In January, the band members filed a suit arguing that the banana has become "a symbol" of the defunct band. They demanded the Warhol Foundation stop licensing the image for use on such goods as iPod covers, and pay them for past licensing. Although they lost, they can still pursue a claim over trademark infringement.

It's a shame because Warhol's recognition of the Velvets' talent was one of his finest moments and resulted in a masterpiece. How much did Lou Reed and John Cale, the group's creative leaders, owe to Warhol? Enough for them to have once dedicated an album, Songs for Drella, to his memory – Drella being his nickname, a contraction of Dracula and Cinderella. How much did Warhol owe them? Well, they saw the best of him and preserved it: their love song I'll Be Your Mirror is in some sense a portrait of Warhol, the artist who reflected the world like a mirror. That may sound like a passive, cold way to make art; but, as the song recognised, to be a mirror is a way of loving a person or the world.

Their pre-banana recordings, with acoustic instruments, are lugubrious emulations of Bob Dylan, drug-slowed folk rock. By the time the band went into the studio to record their debut album, however, they had developed a ruthless steely beauty that had never been heard before. Their clipped guitar lashes, whipcrack viola, industrial drums and Reed's harsh urban poetry held up a mirror to Warhol's world. Reed was like a reporter or novelist at the Factory, giving voices to its lost souls.

It's impossible to separate that great album with its banana cover from the atmosphere of the Factory and Warhol's nocturnal Exploding Plastic Inevitable events. Yet the affinity between the Velvets and Warhol goes much deeper than atmosphere. Warhol's best art of the 1960s, his Death and Disaster paintings, portray moments of finality and catastrophe. That same deathly shock threads like black and silver through the banana album, as much in Cale's avant-garde chair-draggings and devilish strings as in Reed's laconic descriptions of lives lived on the edge.

Warhol's banana – sexual yet starting to rot – captures this album's decadent beauty perfectly. Under his watchful eye, between the folds of his masterful cover, the Velvet Underground created a 20th-century classic.