Election season calls for a game of Real or Fake.

Take this pithy declaration in WhatsApp circulation from 2019, ahead of India’s General Elections: UNESCO Declare India’s “Jana Gana Mana” the World’s Best National Anthem. By now, ‘UNESCO declares India’ anything is a recognisable template; the forward holds celebrity status on the misinformation runway.

Try another. In a recent YouTube short, Prime Minister Narendra Modi comes to life. He speaks about freedom fighter Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in Hindi, before continuing his speech in three other languages. His lip movements are in sync, the timbre of his voice maintained. The short has 190 views. Real or fake? A bit of both.

This election season, misinformation has a new face. This time, it smiles, talks and woos the Indian voter with an ingenuity that is hard to detect and harder to regulate. Mr. Modi’s almost believable speech is a peek into the wide and sweeping force of generative AI to disrupt the largest election season in history.

The 2019 elections were no stranger to hate speech and disinformation campaigns, but the technology that enables this ecosystem has revolutionised at warp speed. The impulse to deceive has found a newer, more eager outlet in the last five years.

If 2019 polls were dubbed the ‘social media elections’, 2024 stands witness to the alarming age of AI elections.

Rights agencies warn, louder than ever, that the average Indian voter in 2024 is at the highest risk of electoral misinformation. There are knowledge gaps in people’s ability to detect what is real and what is AI, leaving them vulnerable to deception and disenfranchisement. Social media companies are struggling to contain fake news and propaganda; the Indian Government is updating existing legislation to better handle the surge in deepfakes online.

The chambers of synthetic chaos have limitless possibilities; in part undermining trust and truth in a democracy. The Hindu spoke with legal experts, activists, and even a professional deepfake maker to place misinformation in a continuum — tracing its growth and comparing its course.

2019 vs 2024: Routes of misinformation

The 2019 General Election was fought on social media. A majority of campaigns by leading parties “incorporated online misinformation into their campaign strategies, which included both lies about their opponents as well as propaganda,” according to a 2022 paper. The researchers identified sophisticated campaigns using forwarded WhatsApp messages and the mass deployment of IT bots on Facebook to disseminate doctored photos, publish coordinated content and post fake videos. The vast majority of erroneous information came from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC); “both parties were also sources and targets of misinformation.” Another report by the Digital Forensic Research Lab showed automated ‘bots’ were boosting hashtags and trying to manipulate traffic on Twitter in February 2019.

The elections also stood out for two visible forces of falsity: ineffectual content moderation in regional languages, and the spread of hate speech. A 2021 Reuters investigation found lapses in Facebook’s policy to moderate regional content: the company did not hire enough workers who possessed the language skills or the local context to flag objectionable content in developing countries like India. The AI tools the company was using to identify these violating bits were ineffective. In the run-up to five State Assembly elections in 2021, Facebook partnered with eight fact-checking organisations to fact-check election-related content in Bengali, Tamil, Malayalam, and Assamese.

The 2019 online campaigning also routinely saw rousing tides of hate speech. But 80% of incendiary posts attacking caste and religious minorities stayed up on Facebook even after it was reported, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, the founder of Equality Labs, told The New York Times earlier. A Vice investigation also found that parties had “weaponised the platforms [of Whatsapp and Facebook] to spread incendiary messages to supporters, heightening fears that online anger could spill over into real-world violence.”

The old channels of mis- and disinformation this year are creating new, cavernous paths, according to experts. Take the infamous IT bots: today’s large language models are enhancing bots with new features and efficiency, imbuing them with a deceptive human-like persona, according to a 2024 analysis published in PNAS Nexus. “Generative AI alone is not more dangerous than bots. It’s bots plus generative AI,” said computational social scientist Kathleen Carley of Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Computer Science in an interview. Put differently, generative AI could make it easier to code bots, expand the reach of manipulated messages and survive longer online.

Other examples are quick to emerge. Parties are reportedly using AI to send messages, form digital avatars, translate speeches in real-time, create memes, generate songs from speeches, and auto-tune content. The appeal of leveraging AI is apparent: the technology is quick, cost-effective, expands the scope of reach and automates the grunt work party workers would generally have to do. A U.S.-based digital marketing firm told Government Technology that AI could help “level the playing field” between well-funded and leaner campaigns.

The evolution of AI fake news

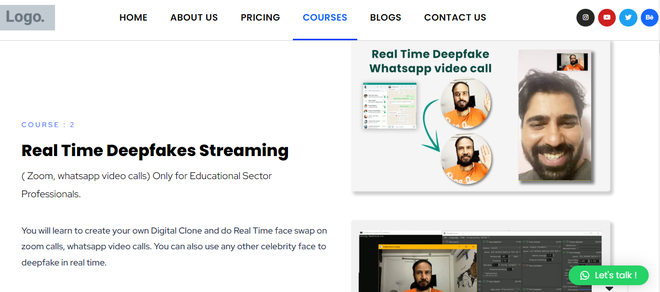

Several months ago, Divyendra Singh Jadoun received an unusual request from a political party: to make a real video look like a bad-quality deepfake. Mr. Jadoun, who heads The Indian Deepfaker channel and company, told The Hindu this “unique” request was so that party members could damage the credibility of the original clip by calling it a deepfake, in case opponents spread this potentially unfavourable video during the 2024 election season. Mr. Jadoun refused to do so.

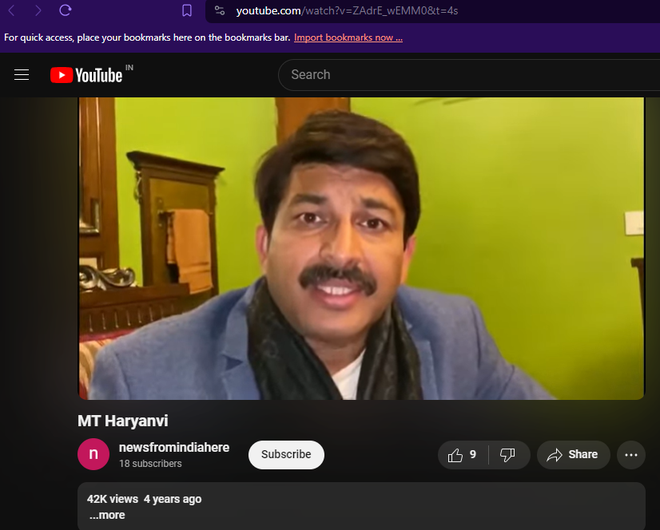

Political deepfakes are not a new issue in India; they have emerged before past elections as well. One example is a February 2020 deepfake video set featuring then Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) President Manoj Tiwari, where he addresses watchers in multiple languages, per the Vice outlet.

The pressing issue now is how such media is flagged, identified, and put into context by digital platforms. Even in the pre-generative AI era, such enforcement actions were nascent or seasonal at best. Now, cheap or free tools make it possible even for amateurs to create deepfakes without being held back by content filters meant to stop the spread of false or illegal content. This means tech platforms have to take stronger action against offenders and break the chain of misinformation quicker than they do.

Mr. Jadoun of The Indian Deepfaker told The Hindu that three years earlier, it would take 8 to 10 days to create a face-swap deepfake video fit to upload on social media - even while using high-end GPUs - because the video had to be converted into frames, which required thousands of images. Now, he says, it takes just two to three minutes or a few rupees to achieve a similar deepfake. The process becomes even easier if the person knows how to code.

“There are two kinds of [political deepfake] requests. One is to enhance the image of the political leader and the other one to defame the image of the opponent,” he explained.

His own company works on personalised video messages for party workers (not voters). Even before the election season, Mr. Jadoun said they would immediately reject pornographic deepfake requests as well as those related to crypto scams.

TID is strict about watermarking its content, and clearly identifies its deepfakes across platforms, but Mr. Jadoun said that tech platforms are at a disadvantage when detecting anything more sophisticated than a low-quality deepfake. He recalled that he previously tried uploading TID’s own deepfakes on Facebook and YouTube, and found that they bypassed the sites’ filters. He also recalled seeing a deepfake ad on Instagram; when he reported it, he said that Instagram informed him that the content hadn’t broken any rules.

So the ten million dollar (or rupee) question is this: will social media giants and major digital platforms walk the talk when it comes to flagging deepfakes?

As of early 2024, YouTube still had not marked the Haryanvi-language deepfake video of BJP member Manoj Tiwari as synthetic or artificially created media. The clip is up on YouTube and has over 40,000 views.

Also Read | AI in elections, the good, the bad and the ugly

The changing algorithm

AI is lowering the cost and barriers of producing election content, and subsequently, election-related mis- and disinformation. Moreover, the algorithms have changed too.

Google has undergone significant layoffs and YouTube is seeing a surge in unlabelled content, including deepfakes, some of which feature notable Indian politicians. In an effort to compete with TikTok, it is trying to monetise Shorts-related content, encouraging to scrolling and long periods of engagement with a greater number of creators. Unfortunately, Shorts videos are also flooded with unlabelled deepfakes and voice clones.

One of the biggest changes in the social media landscape since India’s 2019 elections is that Twitter — the platform used by verified Indian politicians and government institutions to communicate official information to the country’s media — is gone. In its place is the Elon Musk-owned X, which the Tesla chief reluctantly bought for $44 billion. Mr. Musk soon got rid of thousands of employees, including those who worked on trust, safety, and content moderation on Twitter, and then made blue tick verification a paid privilege instead of a mark of authenticity granted to note-worthy or celebrity users. He also monetised several previously free features and rolled out a revenue sharing programme for verified users based on impressions/engagement levels. Another significant development is that paying X users can try out the AI chatbot Grok, now integrated into the platform.

X CEO Linda Yaccarino has continued to remind users that X is a new company, to discourage comparisons with Twitter when it comes to content moderation and floundering relationships with advertisers.

Soon after Musk-owned Twitter began to monetise previously free features, Meta announced its own paid verification privileges for both individuals and businesses. In an effort to fill the Twitter-shaped void for a text-based platform, Meta also launched Threads and scored 100 million sign-ups over mere days in summer 2023, even as it raced to ship essential features.

However, Meta has since stressed that it is not looking to promote political content or hard news on Threads, meaning those who seek to actively follow or engage with journalism or politics have to remain on X, find alternative social media platforms, or individually follow these topics through separate sources.

What does the law say?

Deepfakes are already largely covered under India’s IT rules, which have a framework in place to report and handle morphed images. Here is what the IT Rules say about such media.

Rule 3(2) of the Information Technology Rules, 2021

In essence, social media companies have within 24 hours to take down deepfakes from the time they receive a complaint, whether the media is sexual or political in nature. Anyone can report a deepfake through the platform’s grievance office or India’s cybercrime reporting portal. The government is working to further regulate AI platforms by companies like Google, especially after Google’s Gemini AI chatbot generated statements to the effect that some of Mr. Modi’s actions had been called fascist by experts.

“These are direct violations of Rule 3(1)(b) of [the IT Rules, 2021] and violations of several provisions of the Criminal code,” said Union Minister Rajeev Chandrashekha on X in February. An advisory was issued to regulate AI giants who are releasing large language models while they are still in the testing stage. However, there are concerns that this could lead to censorship.

Google is now working to limit election-related queries, so straightforward questions about politicians and elections result in the response: “I’m still learning how to answer this question. In the meantime, try Google Search.”

Big Tech giants hurry to fortify their platforms

Big Tech giants are gearing up for one election that will affect countries across the globe: the 2024 U.S. Presidential elections in November. However, India’s polling dates are just weeks away. While companies like Google and Meta and even OpenAI have provided assurances that they will work closely with the Indian government and voters to protect their access to truthful information, slip-ups have been observed.

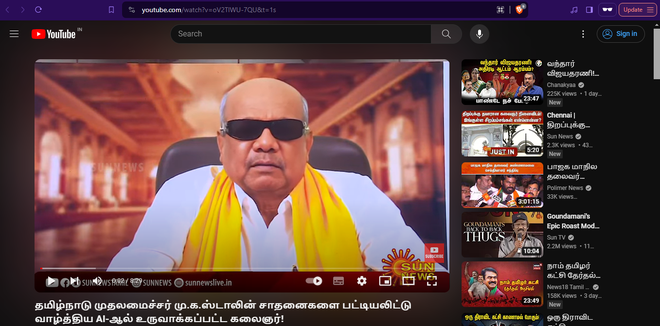

On YouTube, a deepfake video featuring the deceased former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, M. Karunanidhi, was allowed to remain up without labels of any kind.

“We are committed to having the right policies and systems in place to keep our community safe in the lead up to the India elections. We have long-standing and robust policies in areas like manipulated media and elections misinformation, that apply to all forms of content — regardless of the political viewpoints, its language, or how the content is generated. We continue to connect voters with trustworthy and high-quality election news and information on our platform,” a YouTube spokesperson said in response to The Hindu’s query.

The platform also plans to implement rules requiring creators to disclose the presence of synthetic content in their creations. However, the question is whether such measures will be battle-tested and standardised in time for the Indian elections.

Meta has also outlined plans to identify and label AI-generated content, as well as deploy a fact-checking team to combat misinformation — including deepfake media — across its apps. But this will only begin closer to the summer.

“Our policies also prohibit certain manipulated media, as well as hate speech, harassment, and content posted by fake accounts, including videos that have been edited or synthesized using artificial intelligence in ways that would mislead an average person. We also recognize that the increasing accessibility of generative AI tools may change the ways people share this type of content and believe combating this requires concrete and cooperative measures across the industry,” a Meta spokesperson said in response to The Hindu.

OpenAI in late March introduced some audio samples generated by Voice Engine, its text-to-voice model that needs only prompting and a single sample of audio that is about 15 seconds long in order to create natural sounding versions of human voices speaking across languages, with and without accents. The tech has not yet been released to the public.

“We recognise that generating speech that resembles people’s voices has serious risks, which are especially top of mind in an election year. We are engaging with U.S. and international partners from across government, media, entertainment, education, civil society and beyond to ensure we are incorporating their feedback as we build,” said OpenAI in a post, adding that its testers had agreed to usage policies that prohibited the impersonation of another individual or organisation without explicit legal consent.

“In addition, our terms with these partners require explicit and informed consent from the original speaker and we don’t allow developers to build ways for individual users to create their own voices,” said OpenAI.

However, voice cloning tech tools by other makers are just a few clicks away, including one which is an app on the Apple app store. Top reviews claim that users were able to successfully change their voices in order to mimic celebrities.

A need for education

YouTube is teeming with unlabelled videos of Mr. Modi singing Bollywood songs or dancing or even taking part in popular films. But Mr. Jadoun did not think that the makers of such non-watermarked deepfakes were trying to harm people.

“I think the memers play a very major role in creating awareness of this technology. Absolutely, they are helping people be aware of this technology, because people know that Modi is not singing this actually,” he said.

However, Mr. Jadoun said more awareness about deepfakes was needed to protect senior citizens as well as those who were from smaller cities.

During election season, the fangs of false content are sharper. The World Economic Forum in its 2024 survey found India ranked the highest in the risk of AI-fuelled mis-and dis-information globally. Their presence in elections “could seriously destabilise the real and perceived legitimacy of newly elected governments, risking political unrest, violence and terrorism, and a longer-term erosion of democratic processes.”

Unregulated use of AI in electioneering not only erodes public trust in the electoral process, but can manipulate opinions and micro-target communities through opaque algorithmic curations. The Internet Freedom Foundation in an open letter also flagged that “targeted misuse of the technology against candidates, journalists, and other actors who belong to gender minorities, may further deepen inequities in the election”.

In the months to come, more evidence and scholarship will highlight the intricate threads that govern the relationship between synthetic media and voting patterns. But AI electioneering is an old beast in a new disguise: like rallies and meetings, deceptive content has become a fixture of India’s election story in the last five years. In this game of what is real or fake, genuine or generated, the future of India’s democracy and the agency of its electorate is being put to the test.