TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — A federal judge partially blocked enforcement of Florida’s new anti-riot law Thursday, saying it is too vague and could lead to selective enforcement by police and the arrest of innocent people exercising their right to free speech.

The law’s “new definition of ‘riot’ both fails to put Floridians of ordinary intelligence on notice of what acts it criminalizes, and encourages arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, making this provision vague to the point of unconstitutionality,” U.S. District Judge Mark Walker of Tallahassee wrote in a 90-page ruling.

Walker’s order is a temporary injunction preventing police from enforcing the law while the underlying case is tried in the courts. But he specified that it only prevents three sheriffs — in Broward, Leon and Duval counties — from enforcing the new definition of “riot” but doesn’t prevent them from suppressing riots as they could before the law took effect.

Gov. Ron DeSantis has touted the new law as evidence of his support for law enforcement, particularly in light of the riots that occurred in some cities last year amid protests against police bias and brutality against African Americans. Many of those protests were spurred by the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by Minneapolis police.

DeSantis told reporters Thursday the ruling from Walker, who was appointed by Democratic President Barack Obama, was a “preordained conclusion.”

“We will win that on appeal. I guarantee you we will win that on appeal,” DeSantis said.

DeSantis' team added that it would immediately appeal the injunction to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals based in Atlanta. That court recently flipped to a GOP-appointee majority, including two judges plucked from the Florida Supreme Court whom DeSantis placed there, Barbara Lagoa and Robert Luck.

“There is a difference between a peaceful protest and a riot, and Floridians do not want to see the mayhem and violence associated with riots in their communities,” DeSantis spokeswoman Christina Pushaw stated in an email. “We will immediately file an appeal, where we are confident that the 11th Circuit will correctly apply the law and uphold HB 1 to ensure Florida’s law enforcement agencies have the tools necessary to combat riots and keep Floridians safe.”

The lawsuit was brought by the Dream Defenders, the NAACP and other civil rights advocacy groups. They argued in an Aug. 30 video conference hearing that the law has already had a chilling effect on their speech and their right to protest.

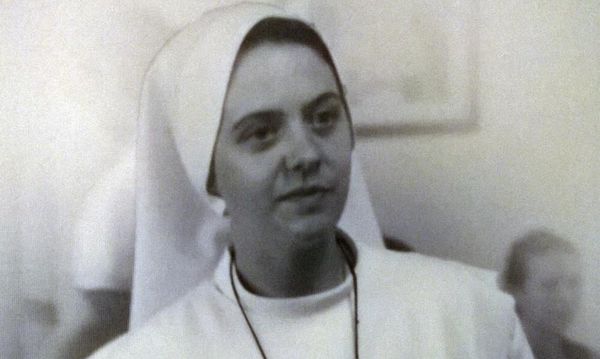

Walker opened his ruling by noting that a fuzzy definition of “riot” had been abused by law enforcement officers in the past, giving the example of Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, two Black students of Florida A&M University who sat in the “whites only” section of a Tallahassee bus in 1956.

“Three police cars arrived at the scene and Ms. Jakes and Ms. Patterson were arrested. Their charge — ‘inciting a riot.’ The rest is history,” Walker wrote.

The vote on HB 1 went along party lines, with Republicans in favor and Democrats opposed, but Black Democrats were the most vocal in denouncing the measure as specifically designed to punish African Americans protesting police brutality.

“HB 1 was more than a political attack on the Black Lives Matter movement. It was an unconstitutional assault on the First Amendment freedoms of all Floridians,” Rep. Omari Hardy, a West Palm Beach Democrat, said in a statement. “I’m thankful that a federal judge has chosen to block this law for now, and I’m hopeful that the courts will continue to protect our constitutional freedoms as the legal challenges to this law continue.”

DeSantis signed the law in April, but he had pushed for the measure since September 2020, saying it was needed to ensure public safety, even though rioting in Florida connected to the Floyd protests never reached the levels in Minneapolis, Portland or other cities in the country.

The law prevents those arrested for rioting or for offenses committed during a riot from bailing out of jail until their first court appearance and imposes a mandatory six-month sentence for battery on a police officer during a riot.

It also defines a riot as “a violent public disturbance involving an assembly of three or more persons, acting with a common intent to assist each other in violent and disorderly conduct” resulting in physical injury to a person or damage to property.

Walker expressed concern with another provision that punishes those “involved in a riot” could sweep up peaceful protesters not engaged in violence. That could violate their First Amendment rights and so the injunction is necessary, he reasoned.

“If this Court does not enjoin the statute’s enforcement, the lawless actions of a few rogue individuals could effectively criminalize the protected speech of hundreds, if not thousands, of law-abiding Floridians,” Walker wrote.

———