No single party looks likely to secure a majority in Portugal’s snap general elections, but for one fast-rising political formation, the vote is already set to be a landmark success.

After taking just one seat in the 2019 vote, current polls show the far-right Chega (Enough) party is poised to claim up to 10 times that in Sunday’s elections.

Albeit at a considerable distance of the two largest parties, the ruling Socialist Party (PS) and their right-wing opponents in the Social Democratic Party (PDS), Chega could thus become the country’s third-largest parliamentary force.

“Chega had one percent of the vote in 2019 and at the moment polls indicate they’ve got around seven percent,” Marina Costa, principal researcher of the University of Lisbon’s Social Sciences Institute told Al Jazeera.

“For a party that first made it into parliament in 2019, that’s a very significant rise,” she added.

Costa argues that the reasons behind Chega’s big increase in support are three-fold.

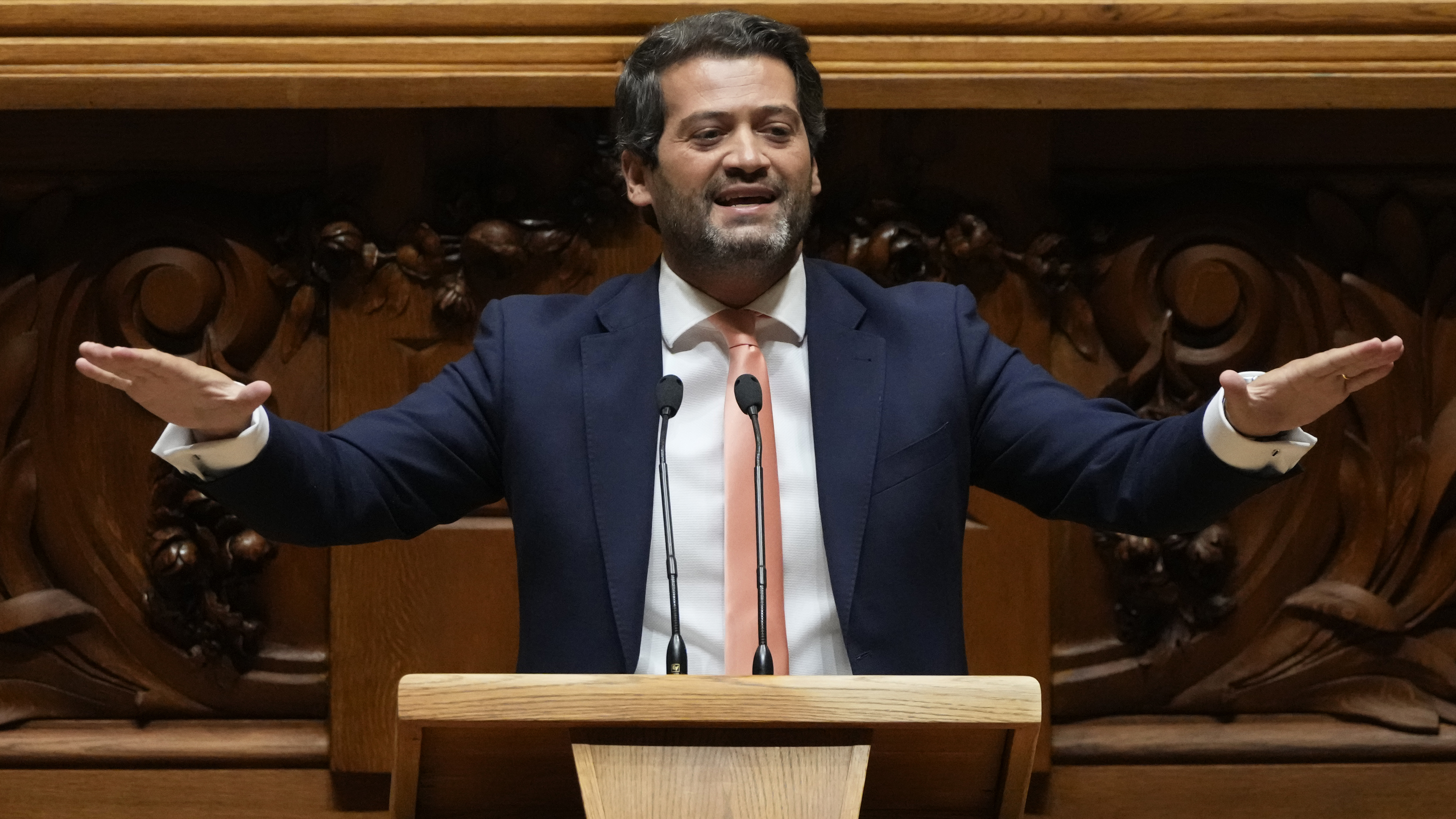

“Getting parliamentary representation was a very important factor when it came to legitimising the discourse of their party leader, André Ventura,” she said.

Second, whereas the mainstream media had shied away from far-right views in the past, they subsequently U-turned to give Chega a disproportionate amount of coverage, she said.

“Chega has received the most attention because of their sensationalist statements, attacks on mainstream politicians and aggressive attitudes. This has obviously paid off,” she said.

“The third reason is that Riu Rio, the PDS leader, has not said that his party would exclude Chega from supporting a minority government. So the right-wing electorate is not obliged to vote strategically. And this raises the numbers of those intending to vote for Chega.”

Chega’s agenda

A typically leader-centric far-right party, Costa says Chega is attempting to bring two main issues to Portugal’s political table.

“One is the subsidy dependence of certain minority groups. Chega claims they are basically getting benefits from the state compared to the middle classes who are paying for them, and that only deserving people should receive them,” she said.

“The other is corruption. It’s an important source of discontent in Portugal.”

José Sócrates, a former Prime Minister for the ruling Socialist party, faces a trial for corruption and “several members of the government were part of the Socrates administration. So Chega attacks the government for a lack of renewal of the [country’s] political class”, Costa said.

Manuel Carvalho, director of one of the country’s biggest daily newspapers, Público, believes Chega’s rise is due both to a partial radicalisation of the country’s right-wing and to Chega being backed by a segment of Portuguese society with longstanding unresolved grievances.

In their voter base, “there are citizens who are really angry about some things that are happening, but if you look at the polls, the fragmentation of the political system is not as great”, he said.

While in Germany the SPD party won last year’s elections with just 25 percent and more than half of the population did not vote for either of the two biggest political formations, Carvalho said, Portugal’s two main parties continue to capture about 75 percent of the country’s support.

“So the central block of Portuguese voters is not as stable as 20 years ago and there are signs of rising support for the extreme right. But that central block is still remaining stable.”

Social discontent

Even so, other social analysts warn that those fighting Chega’s progress should not underestimate current levels of political and social disaffection in certain sectors of Portuguese society.

“They cannot afford to ignore the resentment, the anger, the disillusion a lot of people feel, either,” said Dr Francisco Miranda Rodrigues, president of one of Portugal’s top associations of mental health professionals, Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses (OPP).

“Of course, a pandemic could intensify that because a lot of things have happened which produce powerful emotions: lower wages, losses of certain freedoms, the way we have to live now … And these get entangled in fake news and psychological problems.”

Miranda Rodrigues said Chega also thrives off semi-furtive nostalgia among certain senior citizens for the António de Oliveira Salazar dictatorship, by using “a kind of forbidden speech for the Portuguese after the 1974 Revolution” – which brought back democracy to the country – based on “a kind of collective narcissism about the greatness of Portuguese people and in a way about the history of Portugal”.

Chega has even adopted one of Salazar’s best-known political rallying cries – “God, Country and Family” – for their 2022 manifesto, by just tacking two words, e Trabalho [and Work] at the end of the dictator’s slogan.

But at the grassroots voter level in Portugal, the far right’s rise in popularity and apparent predilection for elements of Salazar’s Estado Novo [New State] authoritarian regime produces very mixed reactions.

“We have a generation of voters that do not really know what happened in their grandparents’ time,” said Alexandre Pinto, a language teacher in Lisbon who is worried about Chega’s increased support.

“Ventura is backed by a politician like Diogo Pacheco de Amorim” – broadly considered to be Chega’s chief political thinker – “who’s been a part of the country’s far right since 1974”, he said.

“And of course he [Ventura] doesn’t say he’s xenophobic, but his messages all go in that direction,” Pinto said.

“I thought their vote was dropping but they’re still third in the polls. Maybe six percent isn’t a high level of support for a political force in other European countries, but in Portugal, with its two very big parties, it is different.”