For a fleeting moment in early October, it looked like the US presidential electoral system might become an issue in this year’s election. The Democratic vice presidential candidate, Tim Walz, told two audiences that the Electoral College should be abolished and replaced by a direct national popular vote.

Walz was shut down quickly by Kamala Harris’ campaign with a brief statement that abolishing the Electoral College is not its official position. Walz duly walked back his comments and the story had a shelf-life of fewer than 24 hours.

But the Electoral College issue may well come back to haunt the Harris campaign should this year’s election produce yet another “runner-up” president – when the loser of the popular vote wins the electoral vote and therefore the election.

If the race is as close as most polls are indicating, this is a possible outcome. And Republican former President Donald Trump is more likely than Harris to be the beneficiary of this archaic, undemocratic voting system.

How the Electoral College works

There is a two-stage, indirect election for the president under the Electoral College system.

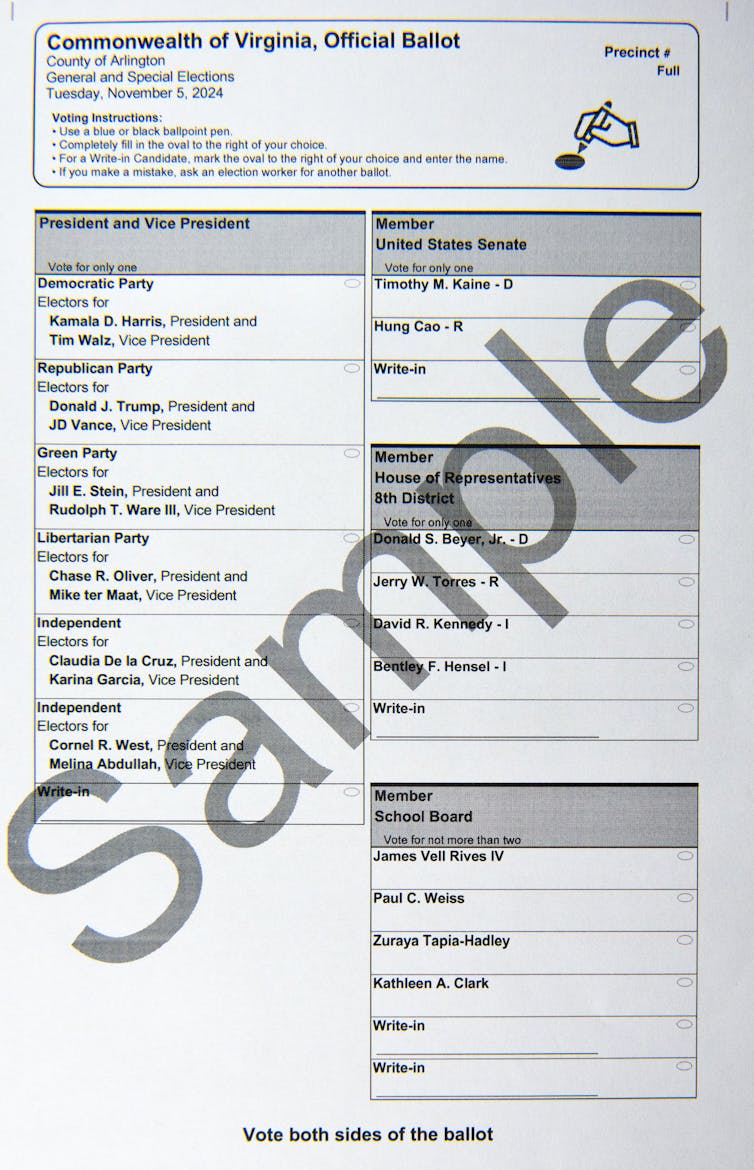

First, there is the popular vote in each of 50 states and District of Columbia on November 5 to choose “electors”, who formally cast the “electoral vote” on December 17 in what is known as the “Electoral College”.

It is the electoral vote that determines the president, not the popular vote.

To make things even more complicated, each state is awarded electoral votes based not on its population, but on its representation in the US Congress.

Each state has at least one member of the House of Representatives and two members of the Senate, meaning every state has at least three electoral votes regardless of its population size.

There are 538 votes in the Electoral College, and an absolute majority of those – 270 or more – is needed to win. The Constitution also contains a complex and highly undemocratic contingency procedure should no candidate win an Electoral College majority. The choice of president would then be decided by the House of Representatives with each state delegation having just one vote.

The origins of the Electoral College

It is not surprising the Electoral College is an undemocratic institution – it was deliberately designed to be. The method of electing the president was an expression of a very conservative philosophy of government embodied by most of the framers of the Constitution when they met in Philadelphia in 1787.

The framers had strong views the presidency should be an office above politics. They also felt the choice should be made by those with knowledge, experience and understanding of government and statecraft.

As such, the framers objected to a popular vote for the president, because they feared it would lead to what one of the founding fathers, Alexander Hamilton, called “tumult and disorder”. The framers were vehemently opposed to direct democracy, preferring instead what they called a “republic”.

Their solution was to allow the state legislatures to determine how the electors from each state should be chosen. In the beginning, most states’ legislatures chose the electors to decide who was president – not the people.

The Electoral College structure – and its philosophical underpinnings – were then locked into the Constitution and purposely designed to exclude the people from the process.

It has also been argued that race and slavery were integral to its design. By piggy-backing on the already-agreed compromise over representation in Congress and the counting of slaves as “three-fifths of all other persons”, the framers of the Constitution handed the major slave-holding states far more clout not only in Congress, but in the selection of the president, as well.

In the longer term, the framers weren’t entirely successful in their efforts because two major political developments in the early 19th century forced some adaptation to the model.

As the American frontier expanded and political parties were developed, people began demanding a greater role in American democracy. This put pressure on state legislatures to cede their power to select electors and allow popular voting for the Electoral College instead.

By the mid-19th century, the Electoral College was operating in much the same way as it does today.

Surprisingly, this required no constitutional amendment because the wording of the Constitution gave the states the flexibility to respond to the demand for popular voting:

Each State shall appoint, in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct, a number of Electors…

But that didn’t change the fact that it was the “electors” who would still choose the president, not the people directly.

How the Electoral College distorts the popular vote

The electoral vote always distorts the popular vote by exaggerating the winner’s margin of victory. In very close contests, it can also go against the popular vote, as it has done on four occasions – 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016.

Two mechanisms are responsible for this.

First, the populations of small states are over-represented in the Electoral College compared to the larger states because of the guaranteed minimum three electoral votes.

For example, Alaska, with three electoral votes, has one electoral vote for every 244,463 inhabitants (based on 2020 US census data). In contrast, New York, with 28 electoral votes, has one electoral vote for every 721,473 inhabitants. So, an electoral vote in Alaska is worth almost three time as much as an electoral vote in New York.

Second, and far more significant, is the “winner-takes-all” arrangement. In every state, except Maine and Nebraska, the winner of the popular vote takes 100% of the electoral votes, no matter how close the contest is.

Even in Maine and Nebraska, it’s winner-takes-all, except those states award two electoral votes to the statewide winner of the popular vote and one electoral vote to the popular vote winner in each of its congressional districts.

Few Americans would be conscious of how the winner-takes-all system works, either.

Put simply, when voters cast a ballot, they are, in effect, voting multiple times – once for each elector in the state supporting the presidential candidate of their choice. They do this by marking just one box alongside their preferred candidate’s name.

For example, if Harris defeats Trump by 51-49% of the popular vote in Pennsylvania, every one of the 19 electors on Harris’ slate will defeat every one of Trump’s 19 electors by the same margin. The popular vote may have been close, but in the electoral vote, it’s 19-0 for Harris.

When that is repeated across all 50 states, the Electoral College vote will always exaggerate the margin of victory compared to the popular vote.

In the 1992 presidential election, for example, Bill Clinton defeated George H.W. Bush by a landslide in the electoral college, 370-168. However, Clinton only edged Bush by 5.5 percentage points in the popular vote (43% to 37.45%). Independent candidate Ross Perot, meanwhile, earned nearly 19% of the popular vote, but because he didn’t carry any states, he got zero electoral votes.

And when the loser of the popular vote wins the electoral vote, such as Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton in 2016, it shows the total number of popular votes won by a candidate is less important than where those votes are located.

To win in the Electoral College, a candidate needs to have their vote distributed economically between the states. In a majoritarian democracy (based on the principle of majority rule), this ought not to be a feature of the electoral system. But the US presidential election process was never designed to operate this way.

Lastly, the Electoral College also heavily determines the nature of the election campaign. Most states in the US are “safe” wins for one party or the other.

As such, the efforts of the candidates are concentrated in the handful of states that are competitive – the so-called “battleground” states. The rest of the country tends to be ignored.

The future of the Electoral College

That the Electoral College survives into the 21st century is partly due to the adaptability of the Constitution to deal with the earlier challenge in the 1800s over the selection of electors in the states, as well as the immense difficulty of amending the Constitution.

This is despite the fact a clear majority of Americans support abolishing the Electoral College in favour of a national, direct popular vote for the presidency.

What happens in this election is anyone’s guess. With the polls showing such narrow margins in the popular vote in the battleground states, the outcome is not only unpredictable, it may even be random. And that’s a terrible comment on the state of American democracy.

John Hart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.