His tone is unmistakable, his solos are breathtaking and his influence is boundless. Even if somehow, some way, you’ve managed to make it this far without knowing his name, undoubtedly, Brian May’s music – most likely with Queen – has been a part of your life.

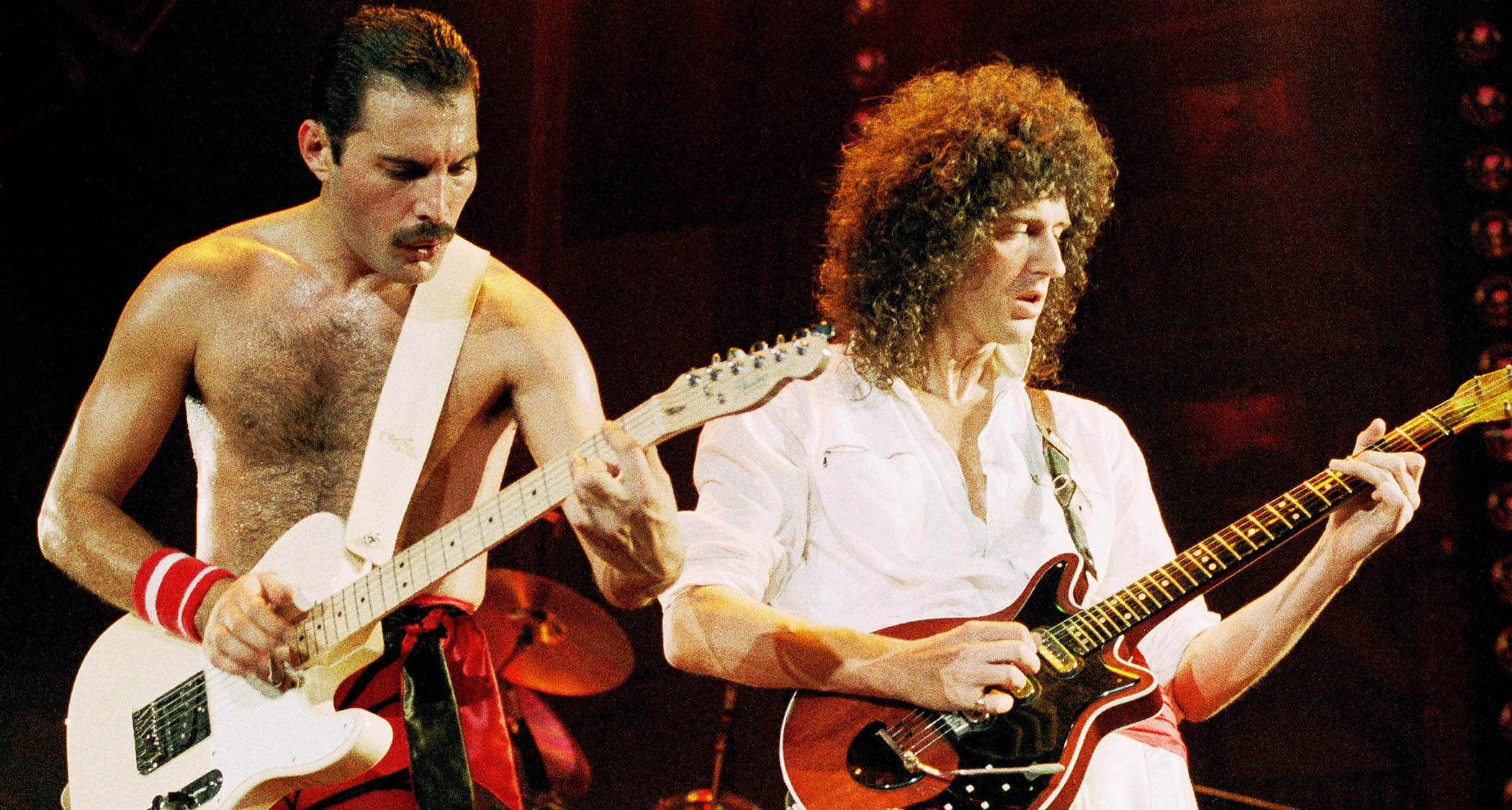

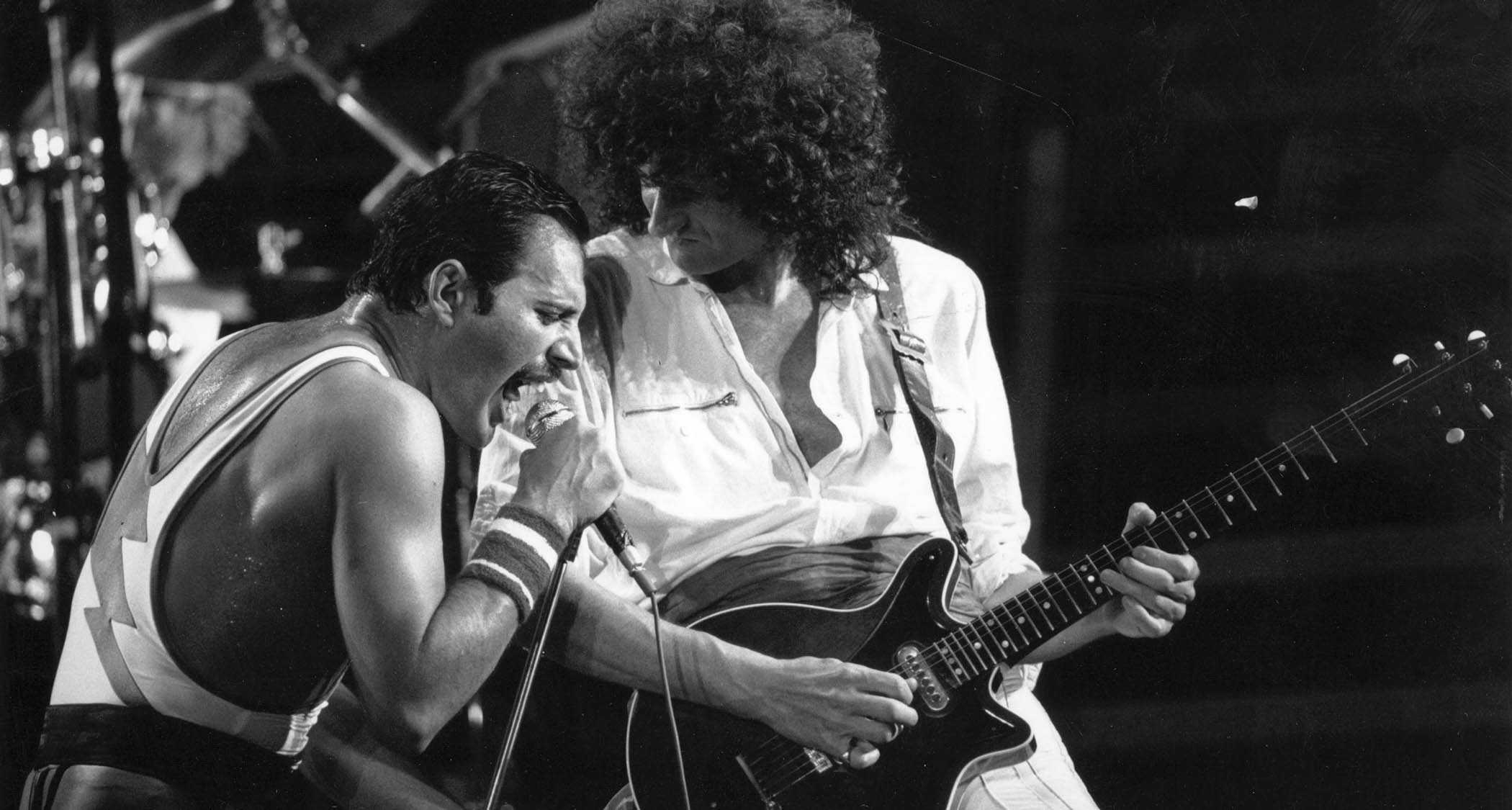

With his trusty, self-built Red Special guitar in hand and a sixpence between his fingers, May – beside Freddie Mercury, his partner in crime – charged through soaring guitar solos and melodic riffs soaked through cuts like We Will Rock You, Bohemian Rhapsody and Hammer to Fall.

Mercury has been gone since 1991, but that hasn’t stopped May from championing the music that Queen created. Since 2011, he’s toured the world as Queen + Adam Lambert with Queen’s original drummer, Roger Taylor, plus vocalist Adam Lambert, the 2009 American Idol runner-up who was tasked with upholding a legacy that was impossible to replicate.

“Freddie would love it,” May says. “I often wish Freddie was around and could share the joy of putting these shows together. But Freddie is with us; he makes little appearances in the shows. So he’s always in there, and I think it should be that way. He’s part of what we built together all those years and will always be massively important.”

Having just finished another slate of mega-shows, you’d assume May would opt for some downtime, but in February – to the surprise of many – he turned up at the grand opening of the Gibson Garage London (aka, “The Ultimate Guitar Experience,” a place where visitors can “try out a guitar, take a lesson, learn about Gibson’s history or see a live show”).

Why, you ask? At the very least, for some hobnobbing with fellow legends Jimmy Page and Tony Iommi; beyond that, we do know May will have a new Gibson guitar coming out in early 2025 – but we’ll just have to wait for the details.

Anyway, mega-tours, top-notch hobnobbing and Gibson collaborations are great, but after more than 50 years in the business, the thing that really brings a smile to May’s face is family.

“I’ve just had a Red Special made for a dear relative,” he says. “When I got it and I opened the box, I thought, ‘Oh, geez, I really don’t want to give this away. I want to keep this.’ But I will give it away. I don’t think I’m ruining the surprise by saying this, but my grandson said he wanted a Brian May guitar for his birthday. He knew the exact specifications he wanted, so I got our guys to make him something super-special.

“He’s taken the bit between his teeth and really wants it,” he adds. “He’s marching down that road without being pushed by anyone. It’s great to see that passion coming out in somebody so young who has got my blood in his veins.”

You were at the grand opening of the Gibson Garage London with Jimmy Page and Tony Iommi. What are your thoughts on that event?

“It was great. It was a really nice opportunity to socialize because none of us do much socializing. You might imagine we do, but we kind of have separate lives. It was good to see them, and the Gibson Garage is great. Some people were saying, 'Well, what the hell are you doing at Gibson? You’ve got your own guitar company.' But actually, I have a great relationship with [Gibson] now.”

I think a lot of people were thinking you might do something with the Red Special associated with the Custom Shop or the Murphy Lab.

“It’s not out of the question. We have spoken about such things, and it would be lovely to have an edition of the Brian May guitar based in the States. After all, that’s where I started with Guild. Guild made the first Brian May models, and then I went with Burns in [the U.K.]. And then things changed, and I just wanted to do it myself. Now we have our own Brian May Guitars company here, but to have the facility to have some made in the States would be wonderful.”

People will always associate you with the Red Special, but as I recall, you did use a Flying V and a Les Paul Deluxe as backups in the '80s.

“I was thinking everybody had forgotten that. But you haven’t! [Laughs] I had a Les Paul Deluxe for a long time; it’s a long story, but sort of a rich sugar daddy of a fan gave it to me. I used it for a while.

“It was a beautiful instrument, but it was never quite right for my gear. So eventually, [since] I always felt I wasn’t deserving of having been the recipient of it for nothing, and having received it for nothing, I gave it away. It now has a nice home, a secret home with somebody else.”

Did you use those guitars on any notable recordings?

“No, I don’t think I’ve ever used anything but my own, with one exception – the Telecaster I used for the solo on Crazy Little Thing Called Love, which is really a James Burton tribute. [The Red Special] makes that kind of sound, you know?

“With all the switching I invented for the guitar, you can have any combination of pickups, and there’s one combination that really sounds like a Telecaster. So we were in the studio [Musicland Studios] with [Reinhold] Mack in Munich, and I’m about to do this solo, which I hear in my head as James Burton.

All my inventions in the guitar are out there for everybody to enjoy

“And I said, ‘You know, I can make this guitar sound like a Telecaster,’ and Mack, being a very ‘doer’ German producer, says, ‘If you want it to sound like a Telecaster, why don’t you use a Telecaster?’ And I went, ‘Fair point.’ Roger [Taylor] just happened to have one, so I used Roger’s Tele, which was a very early Telecaster. I think that’s the only time I’ve used anything but my electric.”

You mentioned the Guild and Burns renditions of the Red Special, and now you’ve got the ones you make yourself. Of all the reproductions, which do you feel is the most faithful to your original guitar?

“The ultimate you can get now is what we call the [BMG] Super. It’s all made by hand, and it costs a lot more because of that. But on this model, you get everything I put on mine, including my self-designed tremolo. Usually, we use other people’s tremolos, which are really good these days, but the one I designed is a bit special.

“With the Super, you get that same design of trem, which rocks on a knife edge, which at that time was revolutionary. Everything else is done custom; my neck is thicker than normal, so you get everything. It’s an exact replica of my guitar, [and it’s] as close as you could possibly get. If I close my eyes with the Super, I don’t know that it’s not my guitar.”

Going back to the ’70s, as the Red Special has ridden along with you, what were some of the things you’ve had to do to keep it up to par?

“It’s been surprisingly resilient; I’ve never re-fretted it, which everyone is shocked to hear. The only fret I’ve ever replaced is the zero fret. And it was designed to be replaced because I knew it was going to wear. That’s where the strings rub when the term’s working, so I think I’ve replaced that twice in its whole history. But not a single fret has been replaced.

“There’s been a little bit of a touch-up to the black surface of the fingerboard. And it’s not an ebony fingerboard; it’s because I couldn’t find ebony when I was building the guitar. I wanted it to be ebony, but it’s multi-layers of Rustins Plastic Coating. Some of those wore through at certain points, so we’ve touched those up.

“We have touched up the body, and it’s mainly Andrew Guyton who’s done that. Although the first repairs were done by Greg Fryer; he also made three replicas, which are fabulous. I still have two of them. Unfortunately, the other one’s gone somewhere; I don’t know where that is. We called them George, Paul and John. [Laughs]”

Which of the two do you still have?

“I have George and Paul. John is out there someplace, I think, because that’s the one Greg kept. So, the neck of the guitar, I’ve never touched; it has lots of layers of plastic coating on [it], and it’s the same as it always was. There’s matchsticks in there with stain on them to fill up the worm holes because it had some dead wood worm in it.

“But it’s never been touched since the day I finished it. It’s worn incredibly well. The tremolo is exactly as it was, with no replacements ever. I replaced a few little rollers; that was an invention of mine.

“Nobody had really dealt with the fact that when you work a tremolo up and down, it scrapes the strings over the bridge. I think somebody had designed a loose bridge, but really, you want each string to be able to move separately because they all move different amounts.”

What did the process of coming up with that look like?

“I made this little assembly – with grooves in the top – out of a piece of mild steel. Then I machined the shiny little rollers to sit in the grooves so the strings could go over the rollers. I think a few people have done that since, but everybody says, ‘Why didn’t you patent it?’ And I go, ‘Well, life’s too short.’

“Patents are a pain in the neck. If you take out a patent, it costs money and takes a lot of time and effort. Then you’ve got to protect your patent, go around the world policing it, and it’s a real pain in the neck. I’ve tried it elsewhere. It’s really not the way you want to spend your life. All my inventions in the guitar are out there for everybody to enjoy.”

You undeniably have one of the most idiosyncratic guitar tones of all time.

“Oh, well, that’s very kind of you to say.”

Some of it is the Red Special, but surely a lot comes from the fingers. What did the evolution of your gear look like in terms of harnessing that tone?

“The truth is, it hasn’t changed very much – except to make it more robust. Talking about amps, I love the [Vox] AC30 sound; to me, it’s perfect. The moment I first plugged into an AC30 with a treble booster, I knew that was me. That was my voice. That was my sound. The only problem with them has been that they’re not very road-worthy, so you have to keep on top of them, maintenance-wise.”

The moment I first plugged into an AC30 with a treble booster, I knew that was me. That was my voice

How do you go about keeping up with them?

“The ones I use now have been completely rebuilt. They started off as classic; they come from the ’70s, but they’ve been rebuilt inside, or hard-wired, and [are] very robust and [have] a lot of ventilation.

“You have to ventilate the valves, or they get too hot, and then performance suffers and eventually they peg out. The guy who does it for me now is a genius. He’s really rebuilt all my AC30s, so they have all the original character, but I think you could probably drop them from a plane and they’d still work. [Laughs]”

Have you gotten much into effect pedals, or is it mostly just the Red Special into the AC30?

“It’s very simple, my rig, except that I’ve always had a stereo chorus built in. That was sort of, again, a dream from when I was a young boy; I realized that if you get a chorus, and you get this lovely, broad effect, if you turn it up, the components of the chorus, the pitch-shifted ones, interfere with the original signal, and it all becomes distortion and you lose your breadth.

That’s how I hear my guitar in my head; it’s always stereo, and it maintains its width when you turn it up full

“Very early on in our career, I found a machine that provides those phase shifts, and it has two separate outputs. One I put to the left side, one to the right side. And those separate outputs have separate amps, so if they go into distortion, they’re completely separate. They don’t interfere with each other; you don’t get the inter-modulation effect, which is so ugly.

“So, you get your breadth; in fact, the breadth gets more and more as you go into distortions. And that’s just kind of my sound, the stereo sound. The middle is straight through, the left is one pitch shift, and the right is the other pitch shift. It’s a very gentle pitch shift, but just enough to give it breadth. That’s how I hear my guitar in my head; it’s always stereo, and it maintains its width when you turn it up full.”

As a tube amp devotee, would you ever consider using an amp modeler?

“I’ve tried modelers, and there are some very good ones now. There’s a great simulator; it’s a pedal [Catalinbread Galileo] that really does a very good job of simulating my sound. But, of course, there’s nothing quite like the original when it comes down to it. In the heat of the battle, all those tiny little peculiarities count, and when I’m at top level and top volume, there’s nothing quite like those amps.

“They have a personality of their own, and I couldn’t swap it for anything. And I wouldn’t like to be on stage with the amps someplace else; I need my amps to interact with my guitar – physically, in the air – and interact with me because I feel it in my body as well. I don’t think I could do the modeling thing live on stage.”

Many people’s introductions to the tone we’ve been talking about came through The Works, Queen’s 1984 album, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. It was a bit more guitar-forward than Queen’s early ’80s albums.

“With me, it always starts off with a burst of activity, belief and inspiration. And thinking, ‘Ah, this is gonna change the world.’ And it’s usually followed by a period of complete insecurity, thinking, ‘Oh, no, this is rubbish. This is never gonna work. Everyone’s gonna, you know, my band’s gonna hate it.’ And then working through it.”

Was it that way for a track like Hammer to Fall, for example?

“I think that’s true of Hammer to Fall because I came upon this riff, [and] I thought, 'This is great. I can do anything with this; this is just what I want to hear when I put my guitar on. This is what the audience is gonna want to hear…' And then I got into the studio and played it to the guys, and they went, ‘Yeah, okay.’ It wasn’t like, ‘We love it!’ And then I got back in and worked on the song.

“That one came fairly easily; I had the idea for the lyric pretty early on, but I had to build it up and build it up to the point where I could play it to them as an almost-finished song. And then they got it; they went, ‘Oh, yeah. Okay, we like this. This is going to be great.’ It takes a bit of belief, I think, to get from the first riff to the point where you’re happy with the result.”

Oscillating between confidence and discomfort is something I think a lot of creative people can relate to.

“I think it’s common to a lot of people – that moment when you spring it on your people around you, and you’re looking at their faces, and you feel very insecure in the moment. When I sing a song to someone, it’s always nerve-racking for me, no matter who it is. If they’ve never heard it before, I get all kinds of insecure. You just have to get over that.

Freddie was very helpful with my insecurities – and he kind of chose me as his guitarist in the early days

“Freddie [Mercury] was always great. I used to sing stuff to him, and he was always very encouraging. Of course, I was generally writing for him. I was conscious that I had to write something that would work for him, not just for me. And generally, he would take hold of it very quickly.

“In many cases, I’d say, ‘Oh, yes, yes, yes, I can do this, darling. Just give me a chance; just put me in there, and I’ll do this.’ [Freddie] was always very upfront; he had an amazing amount of drive, optimism and energy. He was very helpful with my insecurities – and he kind of chose me as his guitarist in the early days.

“Even when Freddie was nothing and nobody, he was Jimi Hendrix in his mind. And I enabled him to have that at his fingertips. He always said, 'You can do anything anyone can do, Brian. You can do this for me.' That sounds like I’m making him out as big-headed, but he wasn’t; it was just this enthusiasm of, ‘We can do this together. We can be the best thing in the world.’”

Freddie’s voice is iconic, but your guitars were almost like a second vocalist because of how distinct your tone is.

“I always saw my guitar as a voice. I was looking for that voice in the early days; I was inspired by those people who first made the guitar speak, like James Burton and, of course, Hendrix and Steve Cropper.

“Those guys, to me, are still the bedrock. They’re the beginning of that kind of expressive playing that comes from country, blues and something inside, which was new. I’ve just had the pleasure of working on a record for Steve Cropper. Do you want to hear the story?”

Let’s hear it!

“My old friend [composer/producer] Jon Tiven has loads of Grammys; I mean… my mantelpiece is not decorated with Grammys, but his is. He’s produced lots of really nice blues records, and he has a very instinctive, light touch. He said I needed to make a guest appearance on the Steve Cropper record.

I was inspired by those people who first made the guitar speak, like James Burton and, of course, Hendrix and Steve Cropper

“I went, ‘I’d love to. Steve Cropper’s a hero of mine, but I’m incredibly busy. I’m not feeling very energetic, and I’m too stressed. Too much stress. Apologies, but I don’t think I can do it right now.’

“That was my email to Jon. Jon emailed me back and said, ‘Okay, I’ve used your email to write the song, and it’s called Too Much Stress. So now, you have to play on this.’ I just smiled and went, ‘Okay.’

“He wrote all the lyrics from my email, and his singer, Roger, sang it and very graciously said, ‘Let’s split the vocals.’ So, I sing it as a duet with him and play some guitar on it. Billy Gibbons also played some guitar on it, so we shared the soloing. It’s become an inspiring project from something that started off as just a whisper. That’s the kind of stuff I love in my life – when things just grow out of a momentary conversation.”

You’ve just given us some insight into what piques your interest, inspiration-wise. But since you’ve been at it for so long and have an established sound, it is difficult to keep from feeling repetitive.

“If you do a lot of touring, it’s incredibly productive in some ways, but it can hold you back from having that freedom. I have been feeling that a little bit. I’m not 35 anymore; I’m 76, and you have a certain amount of energy. If you use it all up by touring, your spontaneous creation side tends to suffer.

“I have been feeling that. This project came as a welcomed beacon to me like, 'Okay, this stuff is still here. You can still go in the studio and create spontaneously; it still happens.' I found that influential in the way I feel right now.”

I’ve been proud of the way we’re playing, but I’m wary of it becoming too much of a formula. I’m always aware of that. I like the freedom to evolve

You still seem filled with energy and have done an incredible job of keeping Queen’s legacy alive.

“I am when I’m on stage. I can do it, and I have the physical capability. I train; I work on that. And I take my training seriously now physically. I think Roger and I are playing together probably better than ever, which is great. We don’t always get on, but we always play together great. [Laughs] We’ve both grown up and mellowed over the years, so we don’t fight as much as we used to, but there’s definitely that chemistry.

“I’ve been proud of the way we’re playing, but I’m wary of it becoming too much of a formula. I’m always aware of that. I like the freedom to evolve, and sometimes, I’ve been questioning whether we still have that. But yeah, I’ve been proud of the shows – especially production; I think our team is amazing. Those shows are way beyond anything we could do in the early days.”

Which of your classic solos are the most difficult to undertake on stage?

“It’s all difficult, really! I think it’s all difficult when you think about treading that fine line between giving people what they want to hear in terms of recognizability and keeping it fresh. So, the little changes that you make consciously and unconsciously need to be there or you become a fossil. [Laughs] I’m always treading that line.”

That stuff never gets easier for me, playing the heavy-riffing thing in Bohemian Rhapsody. You have to keep the energy going; you can’t get too studied about it

Do some songs require more nuance than others?

“Some of them have to be reproduced pretty closely, like the Bohemian Rhapsody solo. That isn’t particularly difficult for me, [but] strangely enough, the riffs in that song are quite difficult. They’re not the kind of places your fingers naturally go to play those riffs in Bb and Ab, which are the keys that Freddie liked to play in.

“That stuff never gets easier for me, playing the heavy-riffing thing in Bohemian Rhapsody. You have to keep the energy going; you can’t get too studied about it. But at the same time, you have to hit the right notes, and, as I say, [they] don’t fall naturally under the fingers. I’ve got to keep a watch on that.

“There are all sorts of things that might not be the things you expect. You know, on Another One Bites the Dust, I didn’t play the rhythm; John [Deacon] played that. He played it on a Stratocaster, I think. He was very much influenced by the punk guitarists, which I’m not so much. So for me to get the feel he got on the record is quite hard.”

How do you approach something like that?

“I approach it from different directions, with different pickup combinations. And with a pick, without the pick, but it’s never quite what John did. I’m always conscious of that, so I told myself, ‘I can’t be John. I can just be me, and I’ll be me [in] the best way I can.’ But that’s not easy.

“It’s not an easy groove for me to hit, especially as you have to hit the ground at 100mph, do it for three minutes and then stop. It’s not something I can organically fit into my playing. People might be surprised; they might think that’s the easy bit, but it’s really not [easy] to do that rhythm. I find it takes an application of mind and body.”

Are there any young players out there today who have caught your ear?

“The young people to me are people like Nuno [Bettencourt]. [Laughs] I know he’s not young anymore, but boy, he’s beyond belief. I know he’s influenced by me; he’s kind enough to say so, but he’s very influenced by Eddie Van Halen, as should be the case. He always pays wonderful tributes to Ed, and he has that magic in his fingers that Ed had, I think.

Nuno, to me, is just stratospheric in the way he plays. These are the people I adore, really. And if I were that kind of person, I would be deeply jealous because I can’t do that shit

“Nuno, to me, is just stratospheric in the way he plays. These are the people I adore, really. And if I were that kind of person, I would be deeply jealous because I can’t do that shit. [Laughs] But I’m not, because I just love it; I love seeing him do it… I’m awestruck by all sorts of people I see on the internet.

“I’m on Instagram and there’s so many kids out there that are just beyond belief in terms of technique. They start where we left off, and I couldn’t even go there. I couldn’t even begin to emulate the stuff they do… Ah, and I should mention my friend Arielle.”

She’s incredible.

“She’s an extraordinary technician who doesn’t let technique hold her down. She’s very expressive, very free and old-school in many ways. She loves analog recording; she loves the old tubes and stuff. She’s a beautiful player. Her tone is magnificent.

“And there’s still this thing in every business where women are slightly undervalued. It’s changing, thank God, but she’s experienced people not quite taking her as seriously as they would have. But she’s an awesome player.”

Do you have any other old favorites?

“For me, my favorites are still, I suppose… I think the generation that kind of follows mine is other people who moved me the most. That’s why I’m so into Nuno. Steve Lukather is an awesome player, beyond belief. I look at him and think, ‘How do you do that?’ He has so many influences.

“His ability when he moves into the jazz area is phenomenal. But he’s a rock player through and through, and his technique is indescribable. I don’t know if he’s on people’s list of the world’s greatest guitarists, but to me, he’s unforgettable and a model of what a guitar player should be.

Steve Lukather is an awesome player, beyond belief. I look at him and think, ‘How do you do that?’

“I should also mention Paul Crook. He took such loving care of our dear friend Meat Loaf. I have great admiration for Paul, not only for his amazing fireworks guitars but also for taking over the production of those albums and absolutely maximizing whatever power Meat had left, who was fighting a hard battle.”

What’s a parting piece of advice for young guitarists?

“Believe more. Smile, be confident and don’t apologize for anything. Just be proud of being yourself, the best you can be. I spent too much time being nervous, uncertain and worried that I wasn’t good enough.

“Be confident, even if you don’t feel it right down in the deepest part of your soul. Play as if it’s there; build on that belief that you put inside yourself that you are good enough – that wherever you are, you’re what it takes.”