European companies have almost doubled their shipments of Russian oil since the start of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, despite desperate efforts by EU leaders to squeeze the Kremlin war machine by blocking Russia’s exports from global markets.

Campaigners said EU-based shipping firms had made a “mockery” of plans to sanction Russia, and warned that a partial oil embargo announced this week would do little to hurt Mr Putin or shorten the war.

The damning assessment came as exclusive new analysis, seen by The Independent, showed the extent to which shipping firms based in Greece, Cyprus and Malta had ramped up their transport of Russian oil around the world in recent weeks, taking advantage of big jumps in rates for tanker cargos.

The shipments have swelled Mr Putin’s coffers by billions of dollars in oil revenue, providing vital funds for Russia’s brutal war, the figures show.

While EU leaders finally reached a deal this week for a watered-down embargo on Russian oil, European tankers laden with Russian crude have plied an increasingly lucrative trade.

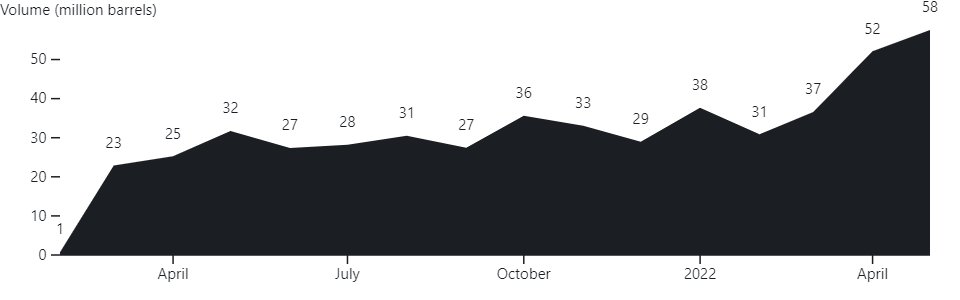

Analysis of Refinitiv shipping data by anti-corruption group Global Witness shows that Europe’s three major shipping countries – Greece, Cyprus and Malta – have rapidly increased the amount of Russian oil they were transporting each month since the war began.

In February, when Mr Putin’s troops invaded Ukraine, companies and vessels linked to the three countries shifted 31 million barrels of Russian oil. In May, that figure had jumped to 58 million barrels. In total, ships linked to Greece, Malta and Cyprus have transported 178 million barrels, worth $17.3bn (£13.9bn) at current prices for Russian crude, since February.

At the start of the war, ships linked to these countries carried a little over a third of the oil exports from Russian ports. By May, that figure had jumped to just over half.

Anastassia Fedyk, a finance professor at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, said the findings were “very concerning”.

“The EU has leverage over Russia due to inelastic energy supply: it is difficult and costly for Russia to divert its energy elsewhere. Allowing EU-flagged ships to carry Russian oil thus only undermines the EU’s own bargaining power.

“An oil embargo needs to be an oil embargo, and this is not an oil embargo,” said Ms Fedyk, who is a member of the International Working Group on Russian Sanctions and a co-organiser of the Economists for Ukraine initiative.

“This is a policy that will partially decrease oil deliveries while promoting some structural changes in the oil logistics industry,” she said.

The European Commission finally announced plans on Tuesday to ban seaborne imports of Russian crude into the trading bloc, but the measures will be phased in over months and have been significantly weakened as a result of wrangling between EU member states.

Russian oil will continue to flow into Europe via a pipeline through Hungary, and after lobbying from shipping interests in Greece, Malta and Cyprus, EU-registered boats and companies will be allowed to continue moving oil from Russian ports to non-EU countries.

That means EU companies can continue to profit from facilitating transfers of Russian oil to countries such as India and China, which have proved to be willing buyers for the crude oil that Europe no longer wants.

China is now the leading importer of Russian oil, having increased its purchases since the war began.

Because many companies have since shunned Russian crude, the minority of companies that are willing to continue shipping it are able to collect bumper fees. A large tanker departing Primorsk could collect $32,500 a day as of Friday, compared with less than $10,000 before the invasion, a shipping industry source said.

Experts and campaigners warned that the failure of European leaders to stop EU-controlled ships carrying Russia’s cargo would leave a gaping hole in the partial embargo.

EU dithering has also punished European consumers, because markets have pushed up oil prices for weeks in the expectation that a tough embargo would be announced, Ms Fedyk said.

“Ordinary citizens in European countries have been paying more for Russian oil without actually punishing Russia – in fact, only increasing Russia’s revenues going towards the war, as the Russian ministry of finance has openly bragged,” she said. The exclusion of maritime sanctions is counterproductive and should be reconsidered urgently, Ms Fedyk added.

While some companies, such as Shell and BP, have sought to publicly distance themselves from Russia’s oil and gas industries, others have stepped in to fill the breach. Among them are companies owned by some of Greece’s wealthiest shipping oligarchs.

There is no suggestion that any of the companies or their owners have violated sanctions or broken the law. But the figures raise questions about the effectiveness of international efforts to financially squeeze Mr Putin’s regime and bring the bloodshed in Ukraine to an end.

Greece’s former finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, said that the country’s ship owners had a vested interest in blocking any interruption to the sale of Russian oil.

However, he argued that the industry contributes “next to nothing” to the Greek economy, because its vessels are often registered in other countries and profits are kept offshore, beyond the reach of Greece’s government.

Louis Goddard, senior data investigations adviser at Global Witness, said: “Since the invasion of Ukraine, European oil tankers haven’t just kept up their deadly trade in Russian oil: they’ve increased it.

“Ships linked to Greece, Cyprus and Malta are making a mockery of the EU effort to sanction Putin’s war machine, keeping cash flowing to Russia as the country’s armed forces continue to pummel Ukraine.

“To close this gaping loophole, the EU must stand firm against lobbying from all member states with vested interests in the Russian oil trade, and put restrictions on shipping at the heart of its sanctions regime.”

Benjamin L Schmitt, research associate at Harvard University and senior fellow at the Centre for European Policy Analysis, said Europe’s inability to completely ban Russian oil meant that “Moscow will continue to feel insufficient pressure to relent in its ongoing atrocities against Ukrainian sovereignty”.

As oil prices have risen sharply, the Kremlin has seen a huge boost to its finances, registering a record current-account surplus in April.

The Russian government is on track to receive an unprecedented $250bn inflow of cash this year, said Clay Lowery, vice-president of the Institute of International Finance.

“This massive inflow of hard currency means there is abundant liquidity and thus low interest rates, which keep Russia’s finances more stable even as its economy deteriorates,” he said.

He added that a maritime embargo could be the key to preventing redirection of oil exports to countries such as China and India.