Twenty years ago an “accounting currency” was born.

This was the single currency of what became known as the “eurozone”: the euro.

Now this wasn’t the notes and coins that most of us associate with the euro. Those were only introduced three years later in January 2002.

That was the moment when the single currency became tangible in the lives of hundreds of millions of people across Europe, and the old deutschmarks, guilders, francs, lira, pesetas and all the ancient constituents of the European monetary mosaic were consigned to history.

What happened on 1 January 1999 was the creation of a rigidly fixed exchange rate and interest rate regime for all those national currencies, so they could all be valued in a common unit. The euro was not yet tangible, but it existed in the ether and in the foreign exchange markets.

It has been a turbulent two decades for the single currency since that launch.

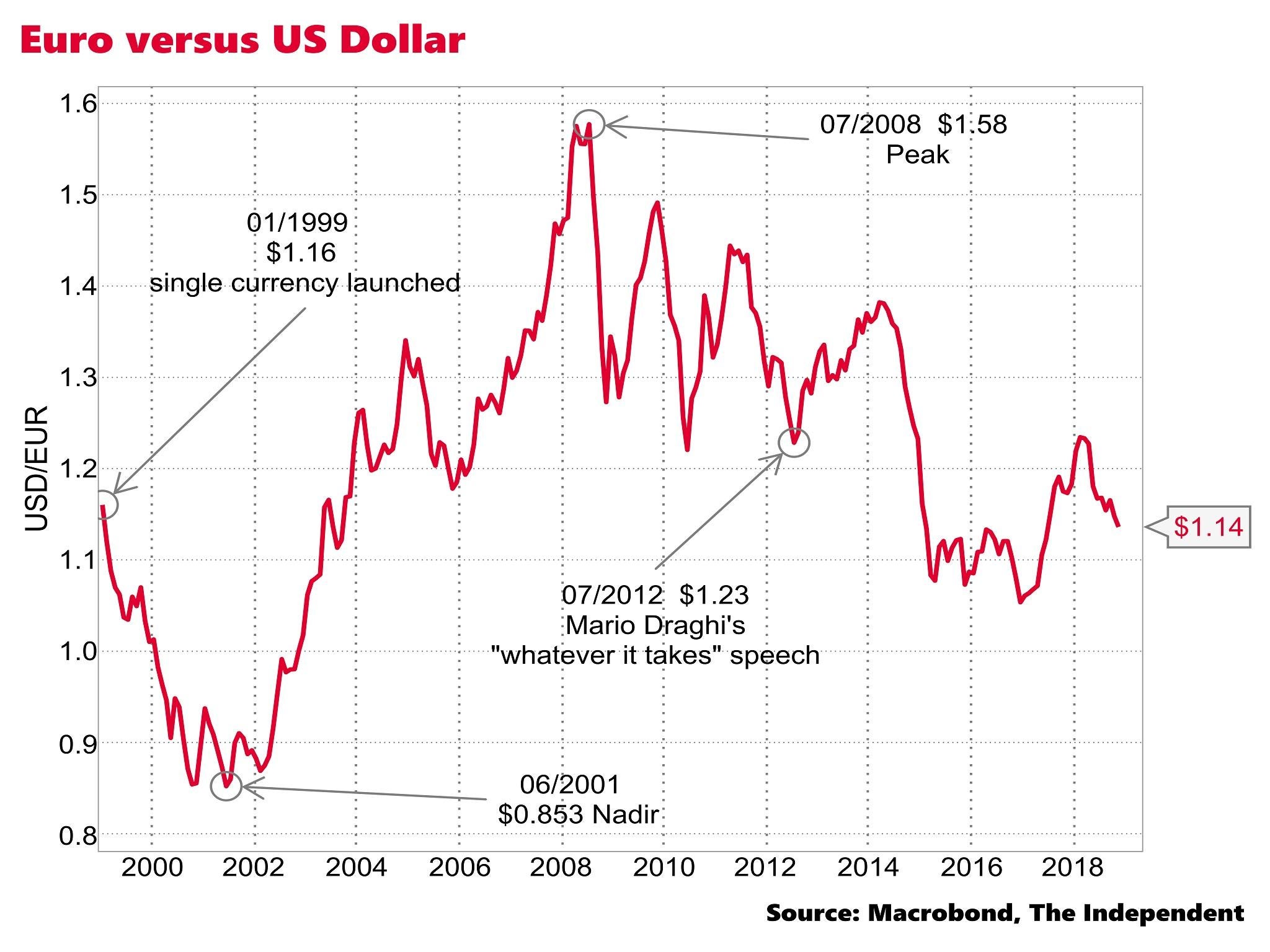

It was not a very auspicious beginning. Having floated at an exchange rate against the dollar of $1.16, the single currency was marked down on the foreign exchanges by traders and investors. It slid to a nadir of only $0.853 per euro in 2001, as the dotcom bubble was bursting.

But then came a long climb upward from 2002, reaching a peak in 2008 at $1.58, shortly before the global financial crisis.

This was a time when rappers like Jay-Z and supermodels including Gisele Bundchen were asking to be paid in euros, rather than dollars.

Turbulent two decades

The euro’s value against the greenback held up through the financial crisis, but a long slide set in in 2014.

To some extent fears of a breakup of the single currency area were taking their toll.

But a more important driver was that the European Central Bank was adopting a more traditionally activist role around that time to support economic activity in the recession-stricken zone – something that normally suppresses a currency’s relative value.

Today the euro trades at $1.14, roughly where it started life two decades ago.

So how successful has the single currency been?

If one were to look at the annual pan-European polling exercise by Eurobarometer, the answer would be surprisingly positive given the turmoil of recent years.

Asked whether the euro has been a good or bad thing for your country, 64 per cent of member state citizens now say that it has been good, up from 51 per cent in 2002.

Surprisingly popular

Other metrics paint a positive picture. The single currency is today used by around 340 million people in 19 countries. It is now an established global reserve currency, stockpiled by central banks and multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund.

Eurozone inflation has been under control, averaging 1.7 per cent over the past two decade, just below the ECB’s 2 per cent mandate.

Yet many economists would snort at the very idea of the euro being a success.

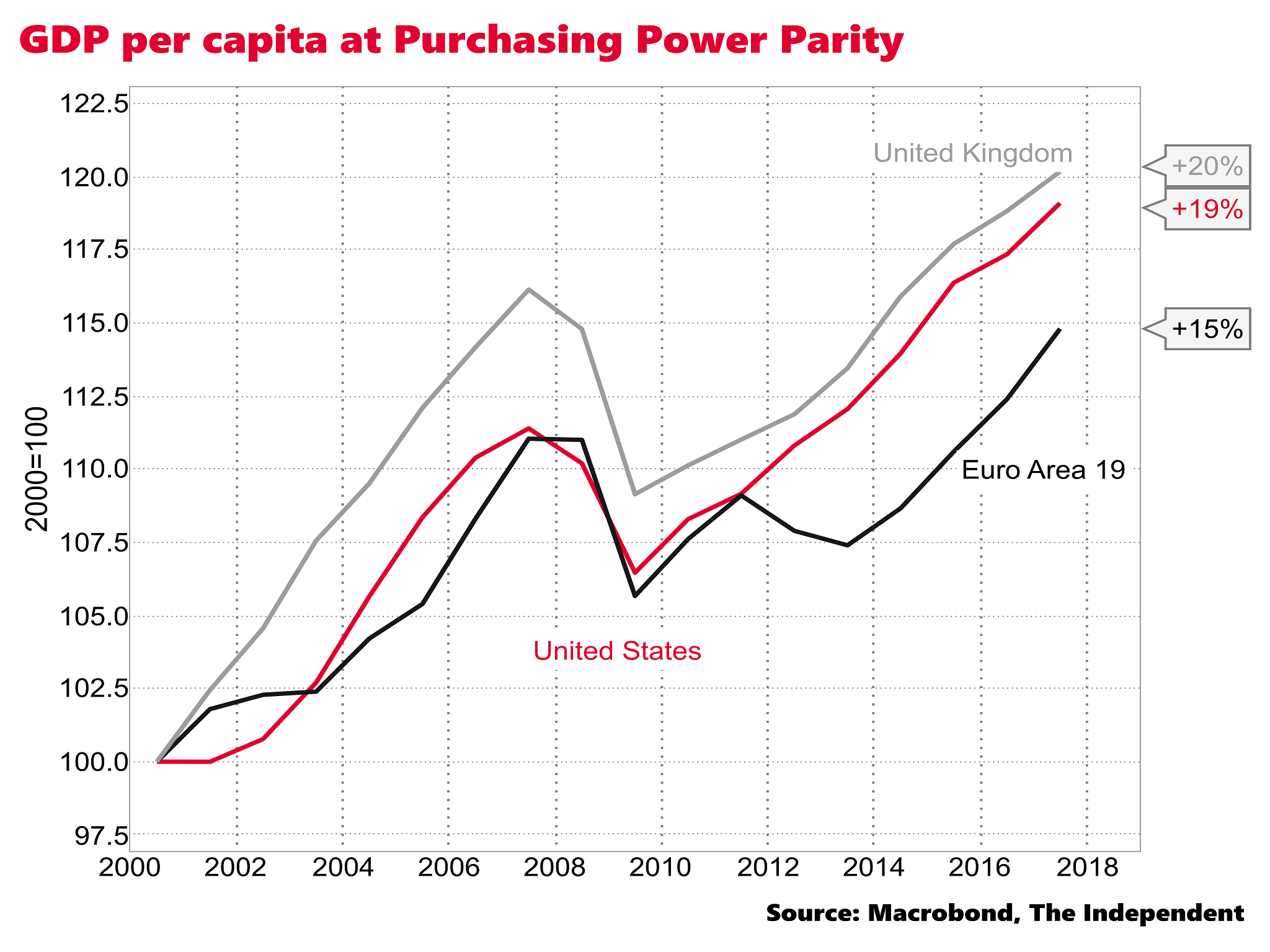

Since 2000 eurozone GDP growth per capita measured (at purchasing power parity) has underperformed that of the US and the UK, growing by 15 per cent versus 19 per cent and 20 per cent respectively.

Relative under-performer

Yet that’s less important than the fact that the single currency was in the throes of existential crisis between 2010 and 2015, when it looked like the eurozone was about to disintegrate as nations such as Greece, Italy, Ireland and Portugal came under unbearable pressure in the bond markets.

Disaster was only averted by a vague promise from the head of the ECB, Mario Draghi, to do “whatever it takes” to keep the single currency together in July 2012.

And many policymakers and opinion-formers in Germany have fought every stabilisation measure of the ECB as a sign that it is debasing the currency and robbing German savers. Those philosophical battles over the responsibilities of a central bank remain unresolved.

Many see this recent history as incontrovertible evidence that the creation of the single currency was a colossal error; that shackling diverse economies, with hugely different levels of productivity and local institutions, together in a common currency, with a single interest rate, was always destined to create disastrous financial, economic and social tensions.

Ashoka Mody, a former economist at the IMF, calls this hubristic step to create a single currency Europe’s “tragedy”.

Optimists say that the near-death experience of the single currency in recent years will spur the kind of integration – such as substantial pan-eurozone fiscal transfers, a banking union and mutual guarantees of member states’ debt – that is necessary to stabilise the currency zone for the long term; that Europe will “fall forward” from crisis to unity, as it has in the past.

Others argue that the single currency has been unjustly scapegoated for failures of national governments, especially Italy, to reform their labour markets and wider domestic economies.

This, they contend, is the reason, not the euro, that such a gulf has opened up between the economic performance of the strong economies such as Germany and the Netherlands and those such as Greece and Italy.

Unemployment rates in the former countries are at record lows, while in the latter group they have still not recovered their pre-recession rates

Tale of two eurozones

But pessimists say that this ignores the extent to which the structure of the single currency facilitated destabilising investment booms in the peripheral states before the 2008 financial crisis and then prevented an appropriate monetary adjustment in its wake.

Their view is that such are the structural contradictions within the single currency that the existential crisis is destined to re-emerge at some point – and it may not take 20 years.