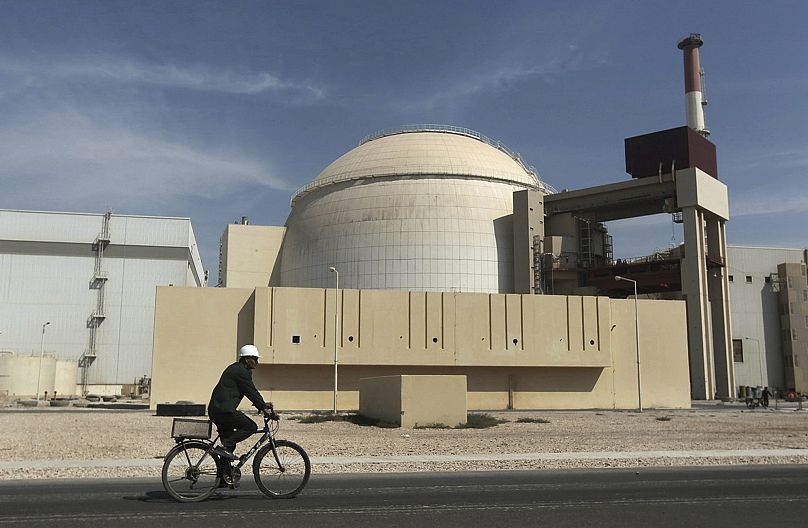

The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), widely known as the Iranian Nuclear Deal, was heralded as one of the major diplomatic accomplishments of its time.

But only three years later, then-US President Donald Trump pulled his country out of it, stating as he had for years that it was a “bad deal” and claiming he could do better himself.

The US’ withdrawal did not entirely destroy the JCPOA, but it did further inflame US-Iranian tensions and made it harder for the deal’s European members to keep it alive.

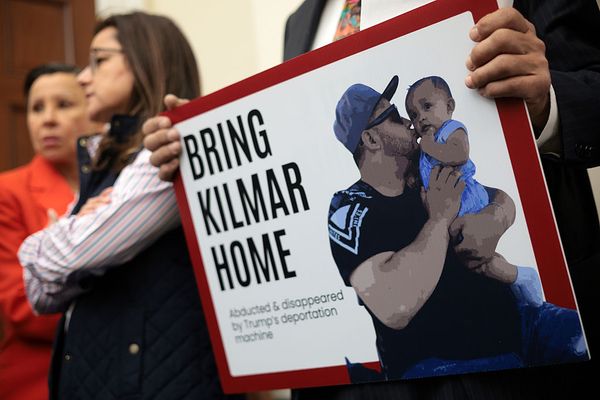

Now, Trump claims “direct” talks are beginning between Washington and Tehran to strike a new deal that will prevent Iran from processing uranium to the weapons-grade threshold of 90% enrichment.

At an Oval Office press conference on Monday, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu alongside him, Trump promised a “very big meeting” would take place this Saturday in Oman to begin the process, which could, in theory, head off a much-anticipated direct attack on Iranian nuclear facilities by the Israeli military.

According to Scott Lucas, professor of international relations at University College Dublin who specialises in US-Middle Eastern relations, it is not easy to see what these talks can actually hope to achieve.

“The real issue here is what demands the Trump people will put on the nuclear programme,” he told Euronews.

“Do we get back to 2015, where the Iranians gave up the 20% stocks and limited enrichment to 3.67%? Trump wasn’t satisfied with that in 2018, so what more can the Iranians do, especially since they’re now starting from a more advanced nuclear position," Lucas said.

"They’ve got 60% enriched uranium that they’re producing, they possibly have the capability to go to 90-plus.”

“It may not be possible to put the genie back in the bottle in terms of getting back to the 2015 terms,” he emphasised.

Edge of disaster

The stakes of not striking a deal are high — as the latter half of Trump’s first presidency made clear.

After dropping out of the nuclear deal, Trump nearly sent the US and Iran into full-on conflict. In June 2019, responding to the Iranian shoot-down of an unmanned drone, he ordered air strikes on Iranian targets, but called them off with the planes still in the air.

According to Trump, he did so after being briefed that 150 people could have been killed.

Then, in January 2020, his administration assassinated one of the country’s leading military figures, Qasem Soleimani, with a drone strike.

Iran responded with missile strikes on Middle Eastern bases hosting US military personnel, and there briefly appeared to be a serious chance of a major eruption.

However, just five days later, Iran’s Revolutionary Guard shot down a Ukrainian passenger jet shortly after it took off from Tehran’s international airport, apparently mistaking it for a US cruise missile. It was several days before the Iranian authorities publicly admitted what had happened, but the incident immediately sparked anti-government protests.

While the Tehran regime survived, the immediate escalation with the US was effectively stalled.

Hard times in Tehran

In the years since, Iran has faced major challenges. It was hit hard and early by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the sanctions and economic problems it has faced made it harder to respond to the virus’ spread.

There have been multiple waves of anti-government protests as younger Iranians, in particular, grew more confident in expressing their outrage at the authorities’ often brutal treatment of women and repression of democracy.

Meanwhile, Israel’s war with Hamas and Hezbollah has badly damaged two of Iran’s most important non-state allies, and Washington is now bombing another, the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

It is in this context that the Trump administration is opening up nuclear talks again. As this weekend’s apparent formal engagement looms, Lucas points out a disparity in how the two sides appear to be approaching the talks.

“The Iranians are sending in their foreign minister, so they’re showing how serious they are about this,” he told Euronews.

“Trump’s sending his real estate developer friend Steve Witkoff, who has been supposedly envoy to the Middle East and then envoy to Russia. He recently gave a blackout interview to Tucker Carlson in which he said Putin ‘really cares’ for Trump and prayed for him after the assassination attempts.”

On the other hand, Lucas said, the basics of what’s at issue are in fact quite simple.

“Even though the supreme leader said publicly ‘We won’t negotiate with a bully’, this is a similar position to the one Iran was in in 2013, when (then President Hasan) Rouhani convinced the supreme leader he had to negotiate because of the economy,” he explained.

“What they want is the lifting of sanctions, point blank. They want to be able to trade, they want to be reconnected to the international system."

"There’s not many other carrots the US has to offer. The issue is going to be, what are the sticks,” Lucas pointed out.

The gathering storm

As far as public statements go, Trump has shown no hesitation in issuing threats, albeit vague ones. “If the talks aren’t successful with Iran, I think Iran is going to be in great danger,” he said on Monday.

His second presidency is already putting new pressure on Tehran in the form of the rapidly accelerating global economic crisis caused by Trump’s sprawling tariff policy and resulting trade war, which has already sent global markets into a tailspin — and oil prices along with them.

“The Iranian economy’s in deep trouble and inflation’s continuing to rise,” said Lucas. “Officially they say it’s just under 35%, unofficially it’s probably way higher than that, especially for food and essentials."

"The currency’s absolutely tanked since November and infrastructure’s in really bad shape, and now they’re going to get hit by the falling oil prices because of Trump’s tariff escapade,” he added.

But while the new global economic crisis may soon hurt Iran directly and hard, any talks will be overshadowed by another problem: Washington's increasing withdrawal from guaranteeing its allies’ security, and the resulting discussion of nuclear proliferation among its allies.

When the 2015 deal was done, the only other immediate nuclear proliferator on the horizon was North Korea, which was already a heavily sanctioned pariah state.

But as of this spring, Russia has several times issued nuclear threats against Europe, while China has continued to build up its arsenal, and some in the US are openly proposing a return to nuclear weapons testing.

As a result, there is increasing talk of European countries clubbing together to share an Anglo-French-led deterrent, and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk has explicitly mentioned the possibility that his country could develop its own independent nuclear capability.