British Columbia has become the first province to be granted an exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to remove criminal penalties for possession of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA for personal use.

This means that police will no longer arrest, charge or seize drugs from adults found with 2.5 grams or less of these substances. Instead, people with drugs will be offered information on available health and social services and assistance with referrals to access treatment if they choose.

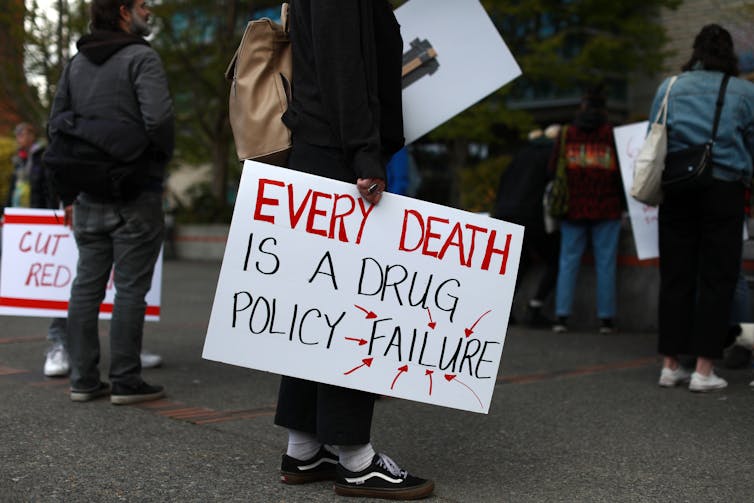

B.C.’s bold experiment to decriminalize “hard” drugs will be closely watched as a comparator with other progressive jurisdictions, such as Oregon and Portugal. Decriminalization in these places has been implemented differently, reflecting the distinctive circumstances and priorities that influence drug policy in different global contexts.

As a sociologist who has been studying drug policy development in Canada for nearly 30 years, it is plainly evident to me that decision-making is a political process that does not rest on facts alone. Drug policy reflects ideological commitments that are influenced by, and in turn influence, prevailing public understandings and opinions about drugs. Exposure to the facts — which are also contested — and constructive dialogue about social norms and values is needed to facilitate more meaningful debate.

Decriminalizing drug use is the realization of 50 years of policy discussions advocating for removal of all penalties for small amounts of drugs. The called-for public health perspective is just beginning to materialize, despite extensive evidence that the war on drugs has failed. The research evidence instead supports the view that prohibition of substance use has been ineffective, costly, inhumane and harmful to the user and society.

Why so little progress for so long?

Canada has long pursued half-measures by adopting a hybrid model recognizing public health considerations within a legal framework that enforces prohibition. The LeDain Commission of Inquiry in 1972 proposed a gradual withdrawal from criminal penalties for illicit drug possession, phasing out incarceration in favour of medical treatment.

The LeDain report foreshadowed the emergence of drug policy with the goal of harm reduction and the need for more attention to the principles that underlie drug policy debates. What is meant by “harm” has been contentious when determining the proper role of law when the police and politicians define harm in ways that justify continued prohibition.

Ten years after the LeDain report, the enactment of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms provided legal tools that complement more scientific evidence-based arguments for drug policy reform. The success of legal challenges on Charter grounds, however, has been largely limited to striking down the most egregious policing practices and penalties for drug crimes.

Sweeping changes in the law might well have been expected with the launch of Canada’s Drug Strategy in 1987. The language change was monumental: it covered the full spectrum of non-medical drug use, including legal drugs like alcohol, prescription drugs and even solvents; and it signalled an intent to set out in a new direction that dramatically departed from the war-on-drugs approach.

The implementation of the strategy, however, was much less so. Police continued to command the lion’s share of funding, despite the promise of pursuing a “more balanced” and coherent public health approach to substance use.

Thirty-five years later, the situation has changed little. In 2018, after decades of debate, but little action indicating actual commitment to reform, cannabis was legalized in Canada, transforming its users from pariahs to responsible consumers. Users of more dangerous drugs continue to be treated differently, primarily because such use elicits more concern for crime control than protecting health.

Lessons from other jurisdictions

In Oregon, the lack of full commitment to a public health approach explains the “mixed results.” U.S.-style decriminalization there has been adopted as a social justice remedy to mitigate the impact of policing on marginalized communities.

In 2020, Oregon voters approved a ballot measure to decriminalize hard drugs as a way to keep addicts out of prison and get them into treatment. Possession of controlled substances is now a “violation” carrying a maximum US$100 fine. The fine is waived if the offender calls a hotline for assessment, which may lead to them receiving treatment.

However, after the first year, just one per cent had used the hotline, and nearly half did not show up to court, prompting criticism that the system is too lenient.

Portugal’s adoption of decriminalization measures has been implemented more successfully, in part because its social safety net is far more comprehensive and better integrated with the criminal justice system.

Portugal’s approach is both more vigorous and nuanced, recognizing that most drug use is “low risk” and requires no intervention. The vast majority of cases referred by the police are deemed non-problematic and the charges are suspended. Those who have a pattern of repeated violations may be issued fines or offered counselling appointments. Substance use dependence and abuse in high-risk cases more often triggers a referral for non-mandatory treatment.

Portugal’s adoption of a graduated system of intervention demonstrates a view that is consistent with coherent harm reduction policy development. Drug use is treated as a health issue. And the proof is in the pudding. Since these measures were enacted in 2001, drug-related deaths and rates of drug use have remained below the European Union average. The rates of HIV infection from injection drug use, and incarceration for committing drug offences, have also been dramatically reduced.

Canada’s adoption of a public health perspective on substance use is hampered by its failure to address the inconsistencies inherent in its hybridized approach. Enacting harm reduction within a prohibition framework perversely criminalizes people recognized as needing help.

B.C.’s bold experiment provides an opportunity to implement more balance in Canadian drug policy, and a more principled withdrawal from the war on drugs. Much can be learned from other places in deciding the path forward, and the world is waiting for new lessons to be learned.

Andrew Hathaway does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.