Curious Kids is a series for children. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au You might also like the podcast Imagine This, a co-production between ABC KIDS listen and The Conversation, based on Curious Kids.

What makes an echo? - Minnie, age 4.

That’s a tricky question. The simplest way to answer is to say that an echo is a sound that later comes back to where it came from.

Before we get into what makes an echo, we need to have a think about sound.

What is a sound?

What we call “sound” is really just the air in our ears moving back and forth.

The air can move fast or slow. We can hear air moving back and forth between 20 and 20,000 times per second. That’s really, really fast! (For the grownups reading right now, human hearing is from about 20 - 20,000 Hertz, which means repetitions per second).

But did you know that there are faster and slower air movements that can be heard by other animals, but not people?

Where does sound come from?

If we hear the air moving in our ears, where did that moving air come from?

A sound can come from anything that vibrates or moves back and forth.

It could start with the moving string of a guitar or the vocal folds in your voice box that move when you speak or sing.

Once the air starts to move, it travels in all directions until it finds something to stop it.

Read more: Curious Kids: Why are we ticklish?

Bounce back!

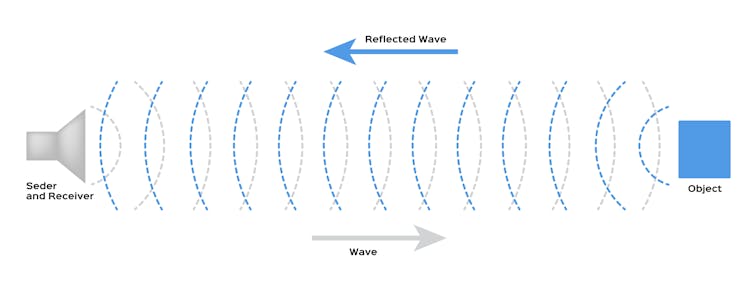

When sound travelling in air (we call this a sound wave) hits a hard flat surface, like a tiled bathroom wall, most of it bounces back. Maybe this is why people like to sing in the shower.

But to get a really good echo, that sounds the same as the original sound, we need a very big bathroom, or another very big, hard-walled place – like a valley or a canyon!

Here’s a video of a man playing trumpet in a canyon. The vibration of his lips makes the sound, which bounces back from the hard wall of rock on the other side of the valley:

For a sound to bounce back and make an echo, there has to be a lot of space between the sound source and the thing (wall or mountain) that it hits and bounces back.

Why? Because it takes time for the sound to come back as an echo. If there’s no big space, it won’t sound like an echo because the sound that comes back will get mixed up with the original sound.

Noticing changes in the sound can still be useful. Some animals like bats and dolphins, and even some children, can use this to tell where they are. This is called “echolocation”.

So if you don’t have a very large bathroom, you may want to try a bushwalk in a valley, or perhaps an underground carpark to find your echos.

If you know of any good echo spots, leave a comment below. I can start you off by telling you that there is a place called Echo Point at Katoomba in NSW.

Did you know?

The name “echo” comes from a Greek legend. In that story, a kind of mountain fairy named Echo was cursed by the god Zeus’ wife Hera so that she could only repeat what was said to her.

Some people believe that when a duck quacks, it does not echo but some scientists in the UK did an experiment and said that was not true.

Many scientists like to study sounds without echoes. For this, they design special rooms called “anechoic chambers”, that stop sound from bouncing back. The Acoustics Lab at the University of New South Wales even has an anechoic pipe. It is so long that any sound that goes in doesn’t come back out.

Read more: Curious Kids: Who made the alphabet song?

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.

Noel Hanna is a member of the Australian Acoustical Society, Acoustical Society of America, Australian Institute of Physics and the Teachers' Guild of New South Wales. He holds the role of Leading Education Professional (Physics) with UNSW Global, a wholly owned subsidiary of UNSW Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.