Shanghai artist Cui Jie is known for her sleek, architectural paintings of China’s ever-changing urban landscapes – so the infinite nothingness of space may, at first, seem an unlikely destination for her. Born at the beginning of the 1980s, during the onset of China’s Open Door policy and the rapid development of its cities, Jie explores this frenetic growth and the accompanying sense of spatial disorientation in her work. For the Shanghai Biennale 2023, however, the event's 14th edition, the artist has left terra firma behind, with three paintings made between 2019 and 2020 that respond to this year’s theme, Cosmic Cinema.

Cui Jie at the 14th Shanghai Biennale

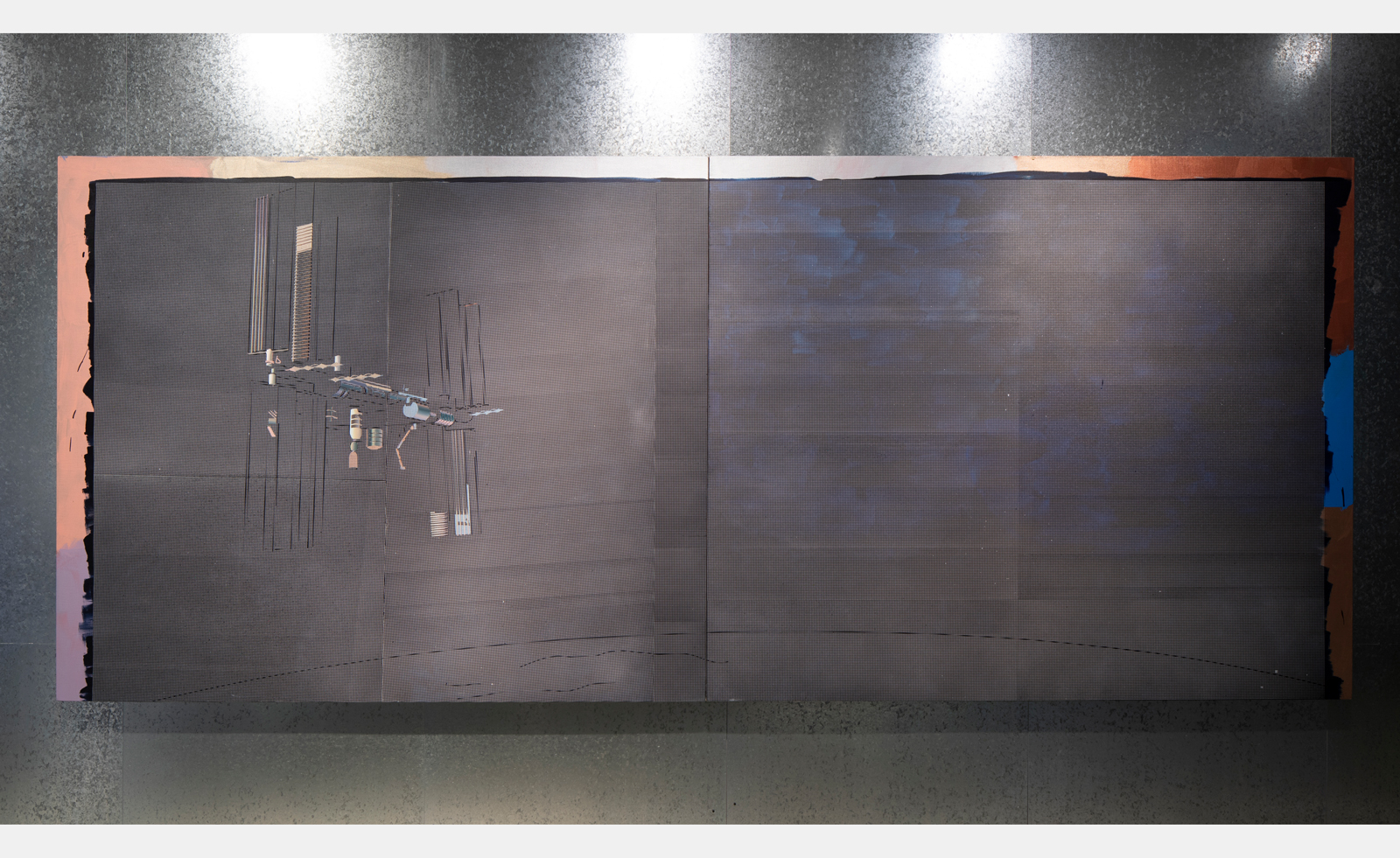

In these works there is little of the imposing, densely layered configurations of glass and steel for which Jie is arguably best known. Instead, each large-scale canvas (the biggest more than two metres long) is immediately striking for its sparseness. In International Space Station (2019), the orbiting laboratory’s skeletal form is only partially distinguished from the dark void that otherwise dominates the canvas, while in The Rainfall Pavilion and the Lakeside Pavilion (2019), Jie selectively illuminates certain angles of a façade, with single lines merely suggesting the rugged outline of a shadowy surrounding landscape.

Both works demonstrate Jie’s interest in territorial sovereignty and the intersection of competing national interests. In her first London solo exhibition, in 2019 at Pilar Corrias, for example, ‘From Pavilion to Space Station’, Jie drew from the layered history of pavilions built on Victoria Peak, a prominent hill in Hong Kong, that hybridise the architectural legacies of Japanese, British and Chinese rule. The illuminated fragments of a building in The Rainfall Pavilion and the Lakeside Pavilion are in fact taken from one such pavilion, built by Hong Kong architect Chung Wah-nan, whose work has often been referenced by the artist. Similarly, the International Space Station is intended as a symbol of global cooperation, but as Russia’s impending departure demonstrates, it also operates as a place of conflict.

Base station #2 (2020) completes the trio of paintings: a satellite mast extending into a dramatic night sky. As often in her work, Jie’s use of colourful underpainting is revealed at the margin of the canvas, swirls of vibrant pools that echo the clouds at its centre. With their gestural forms, these clouds stand in contrast to the sharp geometric lines of the mast and gridded, graph-paper appearance of Jie’s paintings. Like the satellite and the space station, both key communicative infrastructures, these grids serve as the digital webs of data flow that defy international boundaries and, for better or worse, bind us together. Jie’s work reveals how these ties now extend into the cosmos, ready to shape an uncertain future.

The 14th Shanghai Biennale, Cosmos Cinema, runs until 31 March 2024 at the Power Station of Art, powerstationofart.com