The deadly coronavirus outbreak seems to have stoked an increase in xenophobia and anti-Chinese sentiment, according to members of Asian diaspora communities around the world.

Amid sporadic attacks that have occurred in US and European cities, many overseas Asians interviewed by the South China Morning Post said that while they have not personally experienced extreme bigotry or physical attacks, daily “microaggressions” appear to have become more common since the outbreak.

Sophie Xu, a 24-year-old British Chinese finance worker based in Frankfurt, said that many strangers have told her to leave Germany outright, or say “Chinese” or “coronavirus” when they see her in passing.

“A friend of a friend got spat on in the streets by a group of men in Austria – she’s not even Chinese but Vietnamese,” she said.

In just the past week, local media have reported random physical attacks on Chinese or Asians in New York City, Sheffield in England, and Berlin in Germany. In the New York and Sheffield cases, the victims were wearing masks. In Venice, Italy, two Chinese tourists were spat at on the street.

The coronavirus, which originated in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, has killed more than 560 people and infected over 28,000, mostly in mainland China.

But because the virus has now spread to more than 20 countries outside China, numerous countries have placed travel bans on those who have been to China.

Jade, a 23-year-old Chinese British writer in London – who, like others interviewed for this article, asked that her surname not be published due to safety concerns – said that while she had not experienced racism herself, her immigrant parents were worried about their safety because of the reported attacks on Chinese people.

“A man turned away from my dad in disgust when he passed him on the street … I was going to see a film with my dad, but he’s too scared to go out in public where a lot of people are,” said Jade.

“I think media and social media play a big part in stirring up hysteria both in terms of people fearing the disease and people fearing racism,” Jade added. “My parents follow a lot of blogs and media by overseas Chinese people in which racial incidents have been going viral, and this makes them fearful for the whole family.”

Michael, a 23-year-old Chinese Australian civil servant in Melbourne, said that “there’s assumed blame on Chinese people for spreading the disease, especially as there are currently Chinese people quarantined on Christmas Island”.

The xenophobia is not surprising, according to Ying Miao, a lecturer in politics at Aston University in Birmingham, England, since there are few facts about the coronavirus other than it originated in China and most of the cases involve residents there.

“When people are afraid we tend to delve into generalisations and stereotypes, in order to establish a sense of control again. But there is a fine line between trying to minimise risk and trying to assign blame to another race or nationality,” she said.

According to Emma Teng, a professor of Asian studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, disease-related xenophobia towards Chinese immigrants has a long history in the US, which draws the world’s largest Chinese overseas student population.

“Dating back to the San Francisco plague of 1900-1904, Chinese immigrants were blamed for bringing in the disease and the city imposed discriminatory and racist quarantine measures against Chinese residents,” she said.

Last week, the University of California, Berkeley, provoked an uproar on social media for publishing an infographic that included “xenophobia” and “fears about interacting with those who might be from Asia” on a list of “common” and “normal” reactions to the coronavirus.

“Obviously, this new virus is very anxiety-provoking for many, but it is also drawing to the surface latent anti-Asian sentiment that has long-standing roots in American culture,” said Teng.

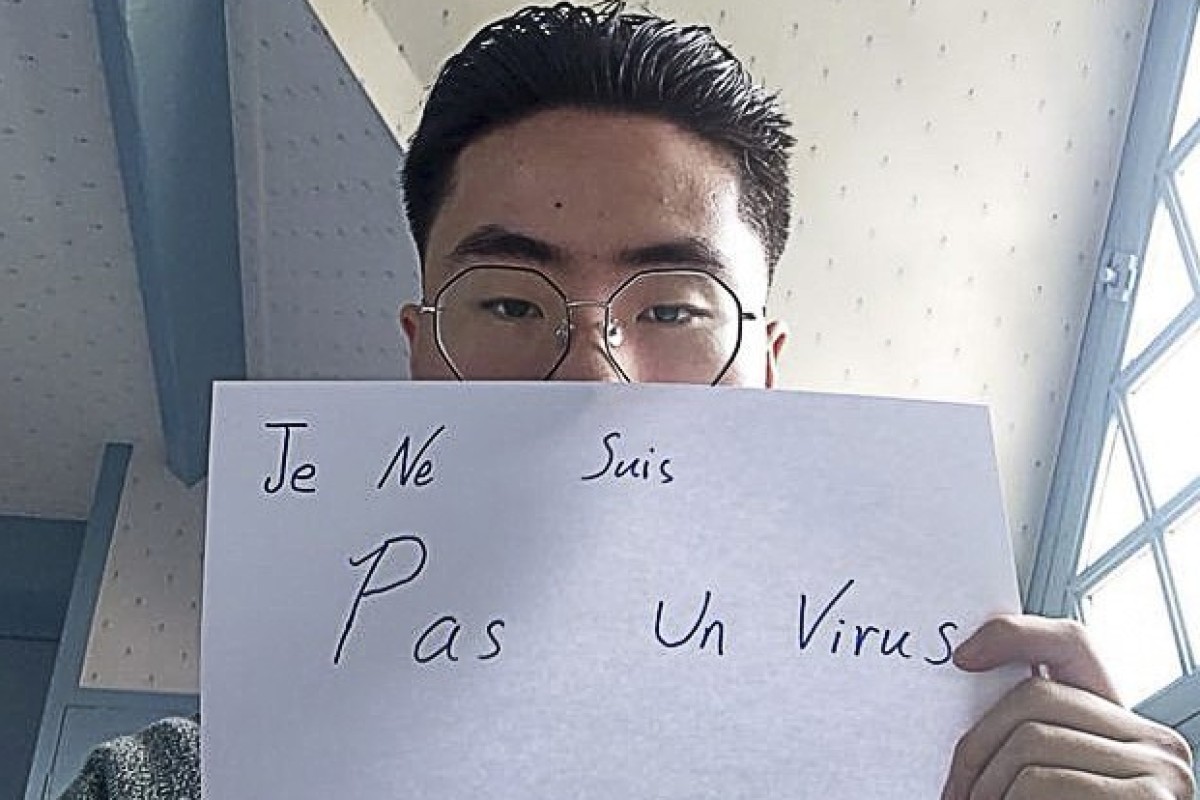

Social media campaigns like “JeNeSuisPasUnVirus” (“I am not a virus”), a hashtag originated by Asians in France to combat xenophobia, have inspired others to take a stand against the growing climate of fear and mistrust.

A Chinese postgraduate student surnamed Ni at the University of Warwick is part of a group of Chinese international students trying to raise awareness of the issue in Britain through community workshops, posters and a coming protest.

Ni said she had seen lots of racist comments online about a clip, from 2016, of a Chinese travel show host eating bat soup in Palau, suggesting that Chinese people are backwards and dirty in their eating habits.

This out-of-context clip, she said, helped to promote the belief that Chinese people eating bats caused the outbreak, which scientists suspect originated at a seafood and wild animal market in Wuhan.

“A lot of British people don’t understand why Chinese people wear masks, and they will jokingly ask whether you drink bat soup,” said Ni.

“Before the outbreak, people would always ask whether Chinese people eat dogs or why our cuisine is so dirty and oily. These stereotypes have always existed, but the coronavirus has brought these prejudices out into the open.”

Ni said she feels anxious about wearing a mask in public, in case she gets attacked or yelled at by a stranger, and is sensitive to others’ reactions if she sneezes or coughs.

“Westerners tend to think that only sick people wear masks, but in Asia it is a protective measure against infections, especially in crowded cities,” she said.

“Asian people will wear them if they have seasonal allergies or even the common cold. But someone else’s personal preference to wear a mask shouldn’t be an excuse to attack them or discriminate against them.

“Even if someone were infected, they shouldn’t be attacked or verbally abused, but instead should receive help and treatment.”

for our 50% early bird offer from SCMP Research: China AI Report. The all new SCMP China AI Report gives you exclusive first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments, and actionable and objective intelligence about China AI that you should be equipped with.