You’ve probably had a sleepless night every now and then. But chances are, you’ve never experienced anything like Trevor Reznik’s insomnia.

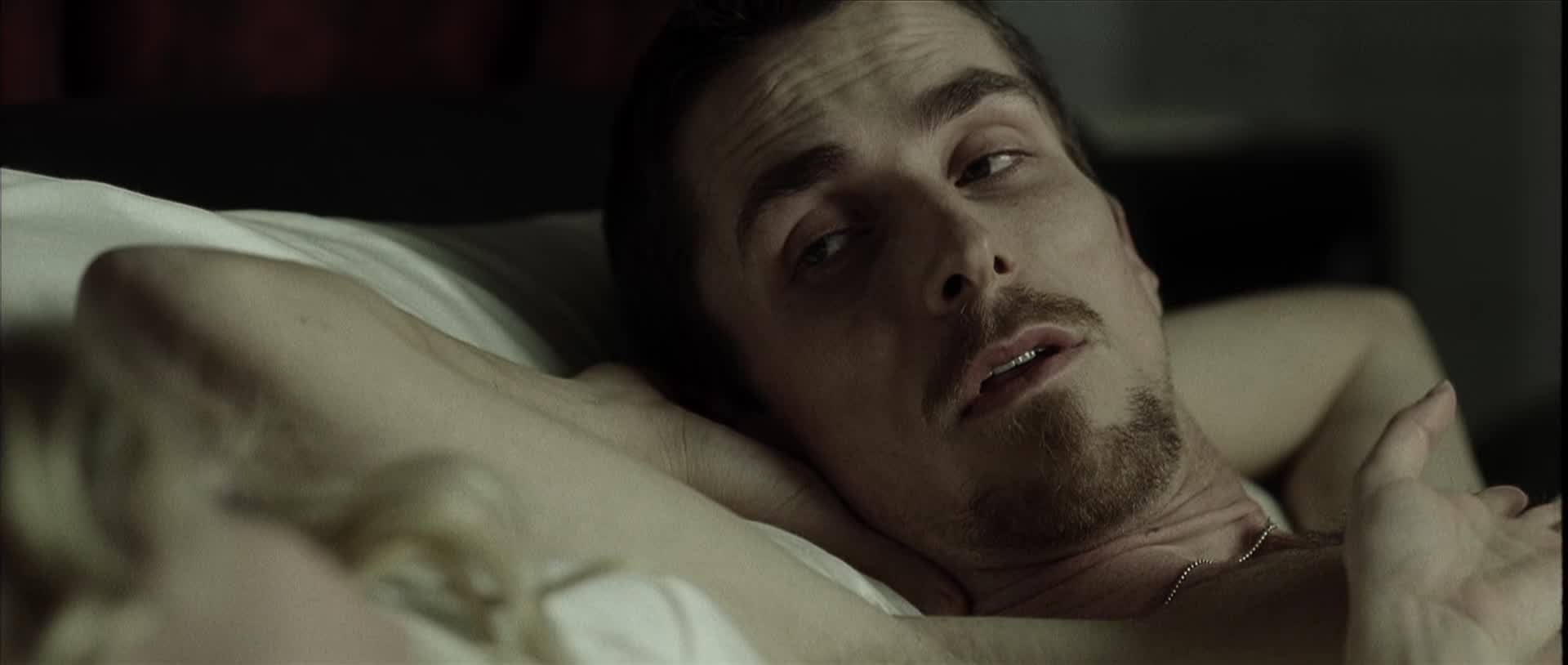

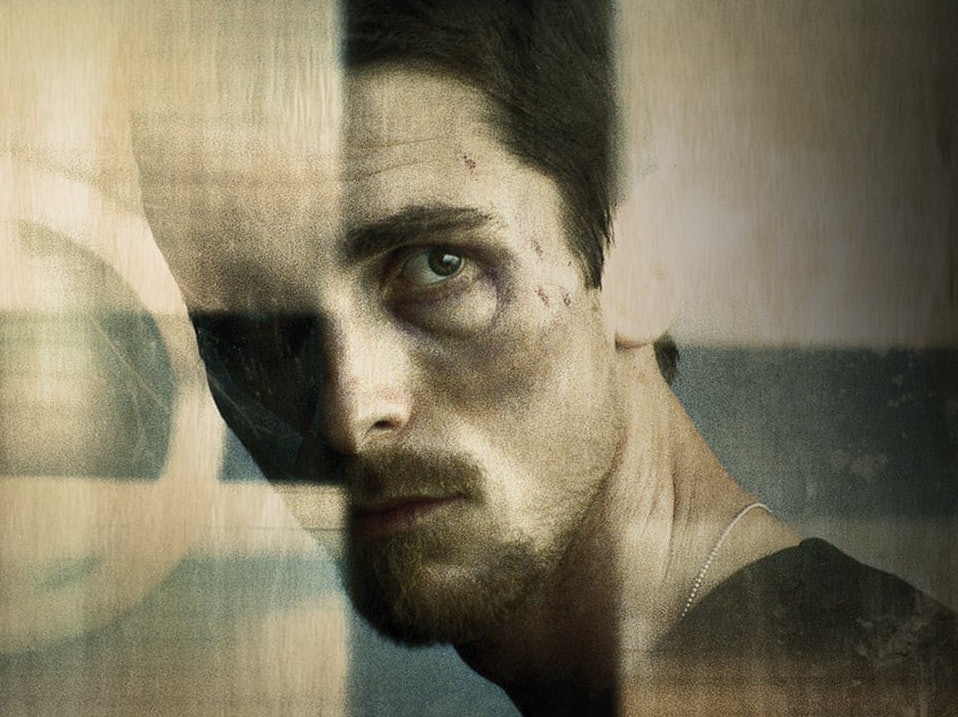

The gaunt industrial worker, played by Christian Bale in the 2004 film The Machinist, has been awake for an entire year. He certainly looks like he needs a rest — coworkers, love interests, and even his boss frequently comment on Reznik’s appearance and question if he’s doing alright.

“To be honest, I think you look like toasted shit,” his boss notes after pulling Reznik aside at work one day. Bale’s eyes carry heavy bags of exhaustion, and his emaciated appearance is emphasized by loose clothes and protruding cheekbones.

And the consequences of this sleepless spell go far beyond Reznik’s physical appearance. As the film progresses, he experiences frequent and increasingly disturbing hallucinations.

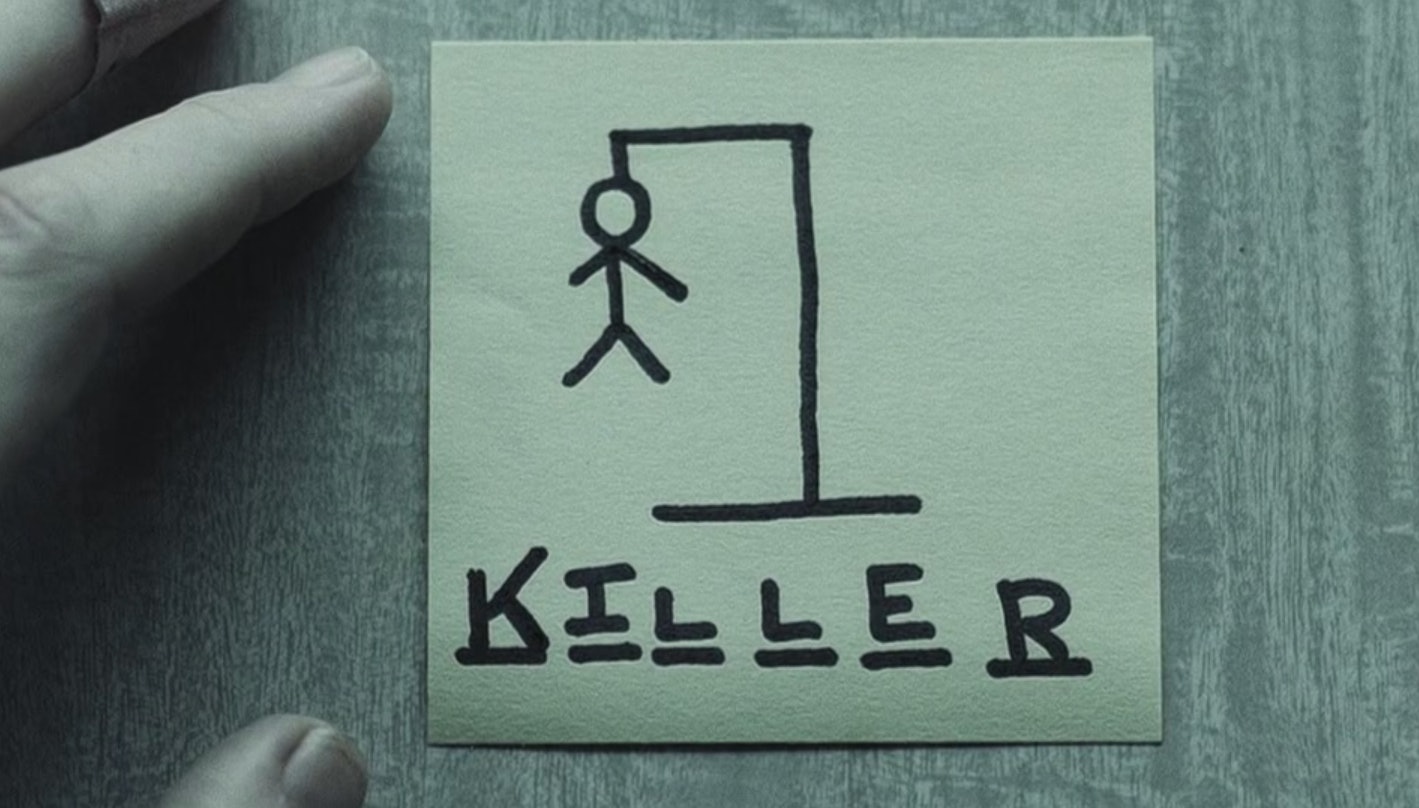

Ominous sticky notes appear on Reznik’s refrigerator, displaying a progressing game of hangman. A man named Ivan shows up at work, but Reznik’s colleagues say he doesn’t exist. At the end of the film (spoiler alert!), Reznik tries to cover up a murder by dumping a body in the river – only to discover the person wasn’t real.

It’s hard to tell where reality ends and distortion begins as Reznik’s life keeps spiraling out of control. His chronic lack of sleep, which doesn’t end until the film’s final scene, wreaks constant havoc in both physical and psychological ways.

In real life, insomnia can be a destructive and dangerous condition. But could someone really go an entire year without so much as a wink of shut-eye?

“It is not physically possible to go that long without any sleep,” clinical psychologist and professor Philip Gehrman of the University of Pennsylvania tells Inverse. At some point, he says, people would uncontrollably fall asleep no matter what.

However, experts say Reznik’s symptoms aren’t totally exaggerated. His convincing hallucinations are a real and strikingly common part of insomnia and sleep deprivation — though his physical changes are not as realistic as the film might make it seem.

A year without sleep?

The Guinness World Record for the longest amount of time without sleep was set in 1986 by Robert McDonald, a stuntman from California. He spent 18 days, 21 hours, and 40 minutes awake in a rocking chair, eventually ending the challenge after struggling to keep food down.

Guinness stopped monitoring new records for the longest time without sleep in 1997. Its biggest reason, as described in a blog post published earlier this year, is due to the physical dangers of sleep loss. Scientists know insufficient sleep can decrease immune function, impair cognition, and raise risk factors for cardiovascular conditions.

But just how bad can it get? Reznik notably comments in the film that “no one has ever died of insomnia.” Unfortunately, there are some situations where sleep loss can be fatal.

“There's actually a rare genetic disease known as Fatal Familial Insomnia where patients gradually stop sleeping and die within a few months,” Eti Ben Simon, a neuroscientist at the University of California Berkeley Center for Human Sleep Science, tells Inverse. “So, yes people can die of complete lack of sleep.”

While fatal familial insomnia affects fewer than 1000 people in the United States, regular insomnia is common — nearly a third of all adults in the world have an insomnia disorder or experience occasional symptoms. Even this kind of sleep loss can also contribute to decreases in cognitive performance, leading to mistakes that can be fatal.

For example, microsleep is a danger for fatigued long-haul truck drivers. Dozing off on the road, even for a split second, can lead to dangerous collisions. It’s also been shown that people who have regular sleep disturbances have higher risk of depression and suicide.

Insomnia doesn’t just mean not being able to sleep. It can also mean difficulty staying asleep and not getting good quality rest. In other words, sleep often becomes fragmented and frustratingly disrupted, rather than not happening at all.

So what happens when someone doesn’t sleep — at all — for a long period of time? From past record keeping and scientific research, we also know that the longer someone continuously goes without sleep, the worse (and weirder) symptoms can get.

“There have been public demonstrations of this … and the results are not pretty,” Jamie Zeitzer, co-director of the Center for Sleep and Circadian Sciences at Stanford University, tells Inverse.

Endurance test

Zeitzer references the famous attempt made by high school student Randy Gardner in the 1960s to stay awake for more than a week. Gardner set the Guinness World Record for the longest time without sleep in 1964 and was monitored by doctors for short and long-term effects.

During the experiment, Gardner experienced a whole host of strange symptoms, according to a report by one of the doctors, John J. Ross of the U.S. Navy Medical Neuropsychiatric Research Unit in San Diego. After two days, Gardner had difficulty recognizing objects by touch and his eyes wouldn’t focus properly.

Moodiness, irritability, and memory lapses followed. By day four, Gardner experienced delusions — at one point he thought he was a famous football player. Hallucinations, slurred speech, and paranoia followed in the later days.

Gardner made it roughly 11 days without sleep. Ross reported that he had an expressionless appearance and barely talked on the final day. At one point, Gardner was tasked with completing a simple cognition test and stopped part of the way through, no longer sure what he was even supposed to be doing.

While Gardner didn’t seem to experience any long-term effects after finally sleeping, the experiment showed that a week without shut-eye can seriously alter how people function. Since then, researchers have observed that many of Gardner’s symptoms are common among people who have been awake for far shorter periods of time.

Matters of the mind

In the past, scientists would conduct sleep deprivation experiments in order to probe how sleeplessness affects the body. Nowadays, with a better understanding of how forcing people to stay awake can cause serious damage, sleep researchers don’t go that route.

“Sleep deprivation studies today are considered unethical beyond 48 hours since the damage to the brain and body is so severe,” Ben Simon says. In studies on rats, she notes, the animals will die within a month without sleep.

Historical studies on sleep deprivation on people can provide a clearer picture of common side effects. In a 2018 analysis of 21 historical studies, researchers found that people typically started experiencing perceptual distortions (alterations to what we see) within the first 24 to 48 hours without sleep.

Staying awake for between 48 to 90 hours leads to hallucinations and disordered thinking. Within that time frame, hallucinations became more complex and started to involve multiple senses. After 72 hours without sleep, people had symptoms that resembled psychosis and toxic delirium, such as extreme confusion, trouble thinking clearly, and disturbing thoughts.

“Hallucinations and perceptual distortions are almost unavoidable after chronic sleep loss,” Ben Simon says. “These continue to increase gradually in complexity, severity, and persistence over time.”

It would make sense in The Machinist for sleep-deprived Reznik to have frequent, convincing hallucinations that seem no different from reality. In real life, researchers are still trying to decode why these sensory effects happen as sleep deprivation progresses.

Awake and asleep

Hallucinations caused by sleep deprivation are a bit different than the ones experienced by people who have psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia, clinical psychologist Philip Gehrman explains.

“It’s thought that when someone is sufficiently sleep deprived they have bursts of REM sleep that intrude into wakefulness,” Gehrman says. “So they’re basically partly dreaming while awake, not truly hallucinating.”

Zeitzer echoes a similar idea. “It isn't proven, but it is believed that what is going on is that part of the brain is asleep while other parts are awake; so, people are simultaneously awake and asleep,” he says.

While the exact mechanisms of these hallucinations aren’t known, it’s clear that sleep loss changes the basic connectivity and activity profile of the brain, Ben Simon explains. Visual hallucinations and distortions could indicate that the visual cortex is one of the first areas of the brain affected when we don’t sleep.

“We also know that lack of sleep has a profound impact on the prefrontal regions of the brain, leading to a gradual loss of executive regulation and logical thought,” Ben Simon adds.

Beyond distorting our perceptions, lack of sleep can cause long-term stress on other bodily systems as well. Research shows that sleep loss can have an effect on weight changes, though not often in the way that The Machinist portrays it.

Minding the physical

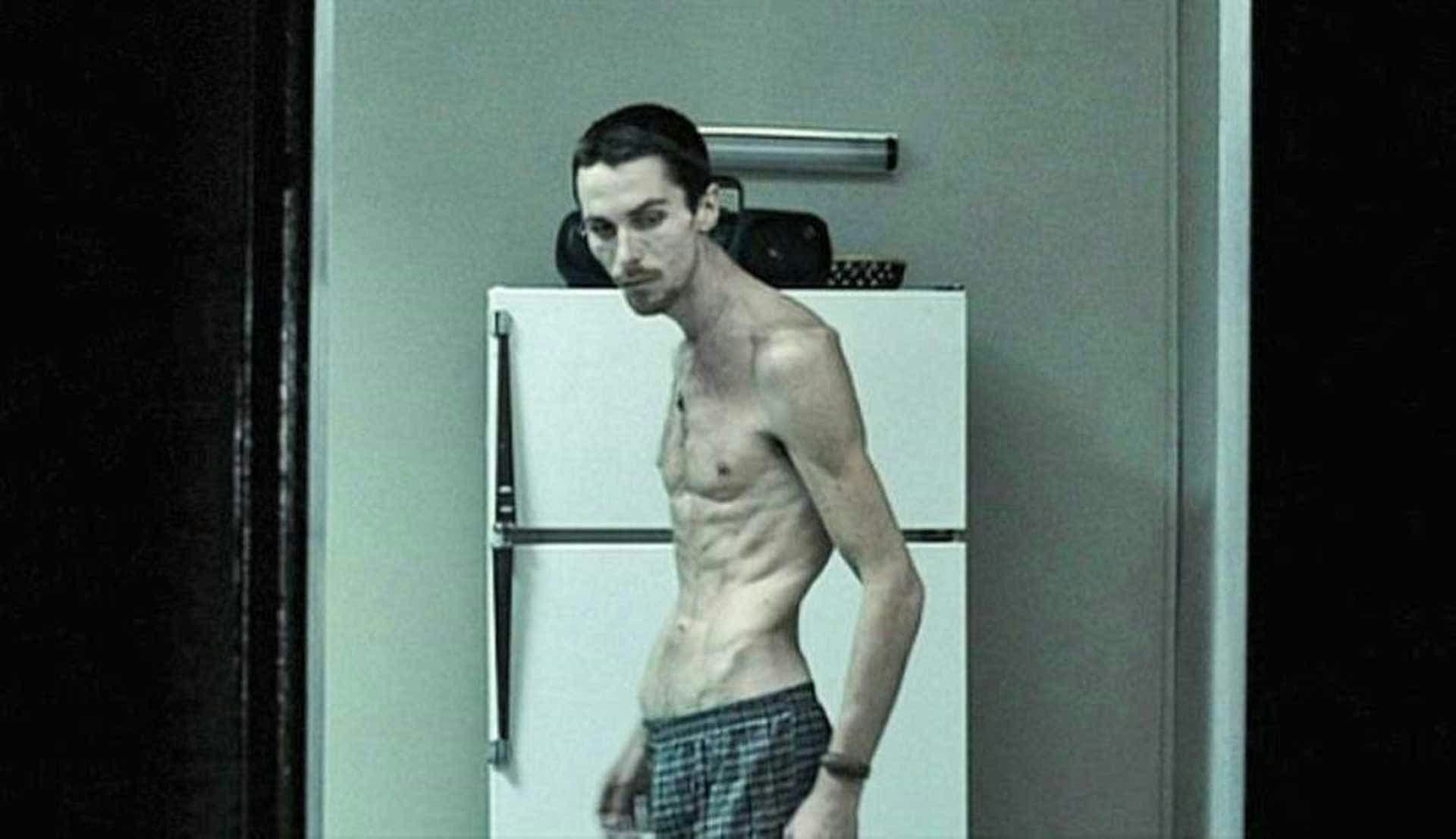

Christian Bale famously put himself on an extremely restrictive, dangerous diet in order to play Reznik in The Machinist. Subsisting on only water, an apple, and a single cup of black coffee each day (plus the occasional whiskey), Bale shed 65 pounds to play the emaciated lead.

In the film, Reznik is rarely seen eating — mostly just smoking cigarettes and sipping coffee. But in real life, chronic sleep loss typically has the opposite effect on people.

“Sleep loss typically increases the desire for high-caloric foods so weight gain is one of the potential risks of chronic sleep loss,” Ben Simon explains.

Gehrman notes that sleep deprivation affects levels of the hormones leptin and ghrelin, which influence our appetites. That’s why we typically get the urge to snack on high-fat and high-carbohydrate foods when we’ve had a bad night’s sleep.

Negative effects on metabolism, too, may also have an effect on weight changes. However, “while sleep deprivation can definitely affect weight I don’t think the effect would be extreme,” Gerhman adds.

The Machinist certainly takes things to the extreme in just about every facet of Reznik’s life, from his physical shape to his sleepless lifestyle.

And while his hallucinations may actually just be manifestations of guilt over an unconfessed crime, they actually aren’t far from the truth — only the people living a similar reality certainly have not been awake as long.