The Albanese government’s new “Measuring What Matters” framework for a wellbeing economy has been criticised for relying on out-of-date data in several crucial measures. But that’s an easy and somewhat cheap criticism to make.

Notably, the Treasury document reports “little change” in overall life satisfaction based on statistics from 2020, and “stable” psychological distress, based on statistics from 2018.

As The Australian newspaper has editorialised, this old data “fails to reflect the COVID-19 pandemic, billions of dollars in extra NDIS spending, and the most aggressive series of interest rate hikes in a generation”.

True, but given these are the most recent years on which the Australian Bureau of Statistics has published data, that’s a relatively cheap shot. It’s as if the newspaper wants to find fault with the document, labelling it “a pitch to progressives” and a “fad”.

The document is more than that. It should be acknowledged as a significant and positive step in the right direction by Australia’s Treasury, in keeping with international best practice.

At the same time, it should be recognised that the measures being used need improvement, both in terms of regularity and how much they capture differences masked by national averages

Read more: Chalmers 'measures what matters' – tracking our national wellbeing in 50 indicators

We’re late to this party

When the then shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers outlined his plan for a wellbeing budget in 2020, his opposite number Josh Frydenberg mocked it as a “yoga mat and beads” approach to economic management.

But the need to shift away from using the blunt instruments of national income or gross domestic product (GDP) to measure progress has long been recognised. Even the inventor of GDP, Simon Kuznets, said a nation’s welfare can “scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income”.

New Zealand, Wales, the United Kingdom, India and Canada are all ahead of Australia in adopting wellbeing frameworks to shape their budget decisions. International institutions such as the OECD and United Nations are working along similar lines.

The new statement is in some ways a restoration of the Treasury’s wellbeing framework developed in the early 2000s under the Howard government, championed by department head Ken Henry and inspired by the work of Nobel prizewinner Amartya Sen. It was quietly dropped in 2016 under the Turnbull government.

The problem with ‘average’ Australians

There are various approaches to measuring wellbeing. One way is to amend GDP by taking out “bad things” (pollution, loss of biodiversity, smoking) and include “good things” not currently included (such as unpaid caring work done in the home).

The approach of Measuring What Matters is to use a “dashboard” of 50 indicators of inclusion, fairness and equity over five areas: health, security, sustainability, cohesion and prosperity. The measures for health, for example, include life expectancy, mental health, prevalence of chronic conditions, and access to health and support services.

For these measures to be meaningful and useful to the budget process, they need to be both timely and capture differences in experiences between different groups – not just the “average”.

Averages can mask significant inequalities. As Paul Krugman put it, if Elon Musk walks into a bar then the average person there becomes a billionaire.

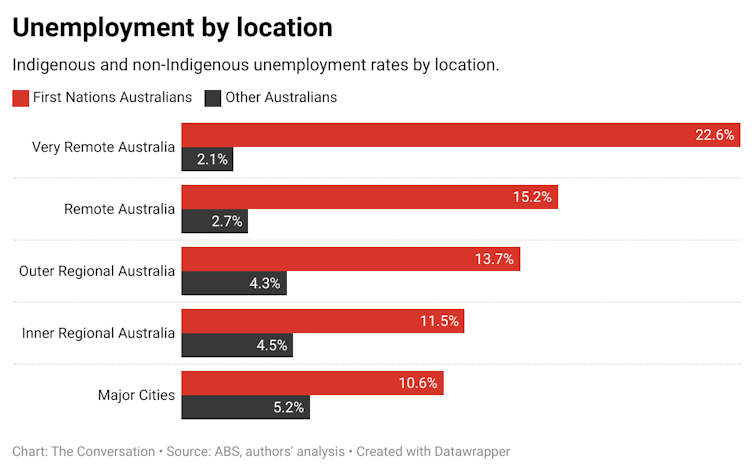

The unemployment rate is at a 50-year low, and average household income and wealth at record levels. But not all Australians are sharing in this. The Indigenous unemployment rate, for example, is still about three times the national average.

As the statement notes, “the whole of population indicators outlined in this Framework are not an accurate measure of First Nations wellbeing”.

Many wellbeing surveys show the importance of understanding the wellbeing of specific groups. For example, the national Carer Wellbeing Survey shows that unpaid carers have much lower wellbeing compared to the average Australian.

Regional wellbeing

Another area where average indicators may be inaccurate is in capturing the experience of people living in rural and remote areas.

Some aspects of wellbeing – such as social connection – are often higher in rural areas. But others are much poorer, such as access to health and social services. People in rural and remote areas are also more affected by drought, flood, fires and storms – events increasing in frequency and severity.

For example, the University of Canberra’s Regional Wellbeing Survey, conducted since 2013, has consistently shown that Australians living in outer regional and remote areas report poorer access to many services, including health, mobile phone and internet access.

Measuring What Matters shows they wait longer to see a doctor and have less trust in institutions. But many other indicators don’t have specific data for rural regions, and don’t provide insight into the often large differences in wellbeing of different rural communities.

Without measures to see how they are faring, we risk leaving rural areas behind.

Read more: Australians' national wellbeing shows a glass half full: Measuring What Matters report

The importance of up-to-date data

Chalmers has rightly referred to the new framework as an “iterative process”.

Yes, the data in some areas is outdated, such as the cost of rent or mortgages and financial security, which come from 2020 – predating the surge in rents and higher interest rates.

The only way to fix this is to provide the resources needed to collect more detailed information more often. This should include ensuring a sample of the many groups known to be at higher risk of low wellbeing but often under-represented in national data collections.

When seeking to move from simplistic to more complex ways of measuring social progress, it is easy to criticise gaps in data, or to suggest that it’s all too hard and we should default back to easier numbers and measures.

But while Measuring What Matters is limited by the scope of the data available, it is a step in the right direction.

John Hawkins worked in Treasury when it had a wellbeing framework. He contributed to a submission about the framework.

Jacki Schirmer receives funding from a number of organisations to conduct research examining the wellbeing and resilience of Australians. These currently include the Australian, Victorian, New South Wales and ACT governments.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.