In the 11th century in Cairo, the foundations for modern science were laid through the detention of an innocent man.

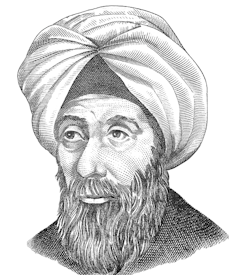

The mathematician Abu Ali al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham had been tasked with regulating the flow of the Nile, but when he saw the river that had shaped 4,000 years of human civilization, the hubris of the task became all too obvious.

To avoid the wrath of the Fatimid caliph in Egypt, Ibn al-Haytham supposedly feigned madness and was placed under house arrest, giving him time to focus on optics.

In doing so, he developed a scientific method based on controlled, reproducible experiments and mathematics. This would not only change humanity’s understanding of optics and how our eyes actually see, but also later lay the foundations for empirical science in Europe.

When I started teaching the history of biology, the importance of this pivotal period of scientific history was often diminished in western analysis of science history. Studying the contributions of non-western scholars has shown me what history can teach us about the value of multiculturalism.

Read more: Explainer: what Western civilisation owes to Islamic cultures

A Eurocentric version of history

The story typically told in the West is that science was invented in ancient Greece and then, following close to a millennium of intellectual darkness, developed in Western Europe over the past 500 years.

Other cultures might have contributed a clever trick here or there, like inventing paper or creating our modern number system, but science as we know it was developed almost entirely by white men. As such it becomes a story of superiority, one that demands gratitude.

The scars of this way of thinking are all over our geopolitical landscape. It shapes how many western leaders interact with other cultures, apparently entitling them to share their intellectual authority without needing to listen to others. It is a mindset that belittles other civilizations and led to centuries of colonial violence.

This Eurocentric version of scientific history omits some of the most important events that shaped modern thinking. Science was not developed so much by individuals but by a highly complex global process that brought together ideas, lived experiences and approaches from all major civilizations.

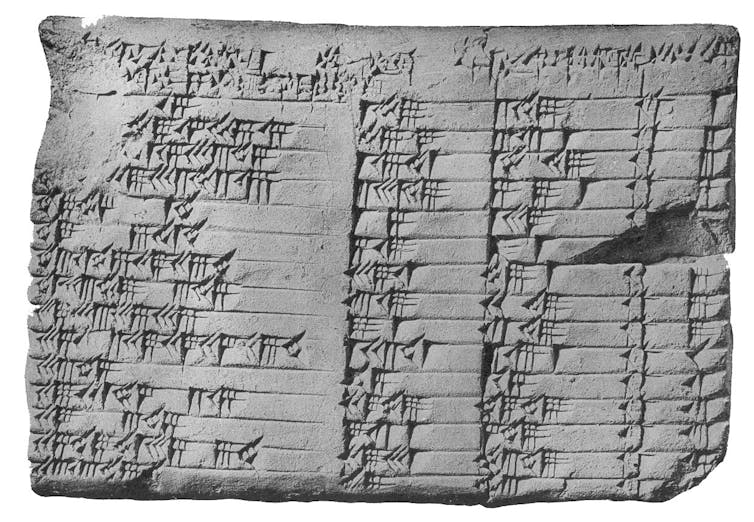

Read more: What was the first thing scientists discovered? A historian makes the case for Babylonian astronomy

Ancient Greek scholarship, for instance, was indeed instrumental in developing science, but it was not inherently western. The Greek empire spanned much of the Mediterranean region and the Black Sea. Scholars travelled extensively, and the centres of scholarship drifted over time from Ionia in present-day Turkey, for example, to Athens to Alexandria in Egypt.

Greek natural philosophy was influenced by the mathematical and astronomical achievements of the Babylonians and the medical traditions of the Egyptians. Later, Alexandrian scholars made great advances in human anatomy when they overcame the Greek aversion to dissections, likely because of Egyptian influences. Natural philosophy was born from the merger of these scholarly traditions.

Importance of testing ideas

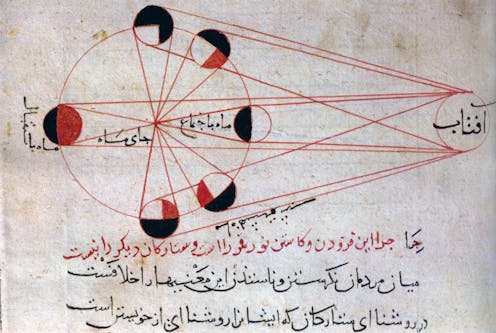

Similarly, Ibn al-Haytham was one of thousands of scholars who, during the golden age of Islam, were engaged in the immense task of translating, combining and developing the world’s knowledge into great encyclopedic texts. They admired Indian and Chinese scholarship and technology but revered the ancient Greeks.

While the Greeks had an impressive greatness of mind, they had largely shunned the idea of experiments and believed that developing instruments was the job of slaves.

Many Arab scholars, on the other hand, emphasized the importance of experimentally testing ideas and developed scientific and surgical instruments that allowed for significant advances.

Arguably, Arab scholars built the foundations for modern science by developing a method for controlled experimentation and applying it to Greek scholarship combined with knowledge and technologies from all accessible parts of the world.

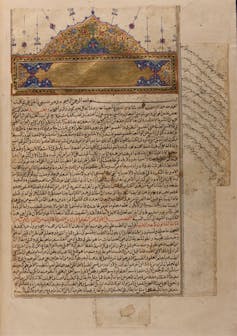

Later, Latin translations of the Arabic texts would allow science to grow in the West from the intellectual ashes of medieval Catholicism. Texts like Ibn Sina’s Qānūn fī al-ṭibb (Canon of Medicine) would become standard textbooks throughout Europe for hundreds of years.

Ibn Al-Haytham inspired scholars like Roger Bacon to work toward European implementation of the scientific method. This would ultimately lead to Europe’s scientific revolution.

Read more: Avicenna: the Persian polymath who shaped modern science, medicine and philosophy

Importance of intercultural exchange

Great civilizations existed all over the world in the beginning of the 16th century, in Africa, the Middle East, the Americas and East Asia. Most had scholarship that was superior to the West’s in at least some respects. Arguably, the most valuable thing Europeans took from the rest of the world was knowledge.

The first vaccine, for instance, was based on variolation techniques developed in China, India and the Islamic world. People were inoculated against smallpox by blowing powdered scabs up their noses or rubbing pus into shallow cuts.

Europeans believed that diseases were caused by bad air (miasma) and so did not initially trust this technique. It only became widespread in Europe and North America after English aristocrat Lady Montagu saw its efficacy firsthand in Constantinople in the early 18th century and advocated that it be tested in England.

A vaccine developed by English physician Edward Jenner 80 years later was simply the well-known variolation technique made much safer by inoculating with cowpox instead.

The importance of intercultural exchanges should not be surprising. Scientific data and observations are ideally objective, but the questions we ask and the conclusions we draw will always be subjective, shaped by our prior knowledge, beliefs and past experiences. Different cultures can help each other see beyond their inherent biases and grow beyond the intellectual constraints of individual approaches.

In her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, Potawatomi botanist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer gives a beautiful example of this in the context of how Indigenous approaches can inform modern science.

One of Canada’s greatest gifts is our diversity. Here, cultures from across the world come together, forming a multiplicity of minds that is well positioned to solve the problems of our world. However, this only has value if we can connect and learn from each other. When we advocate for a diversity of ideas in curricula, both nationally and abroad, we are promoting a future built on the knowledge of people and cultures from around the world.

There is nothing more intimately personal than the thoughts in your head, and yet you did not conceive them. They are a continuation of knowledge and ideas that for thousands of years have travelled the globe, shaped by countless minds from all civilizations. In a time of seemingly growing division, that is a thought that ought to bring us all together.

Karen K. Christensen-Dalsgaard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.